Amazon culture clash over Brazil's dams

- Published

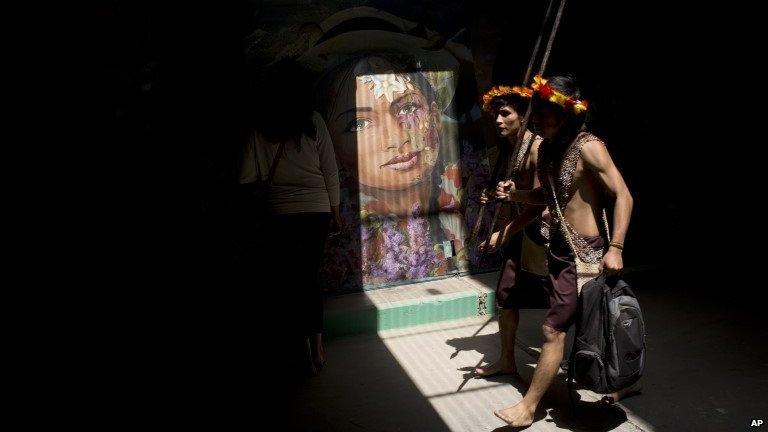

The Munduruku are wary of the plans to build more dams

A battle is under way in the Amazon region of Brazil between indigenous groups and river dwellers on the one hand and big corporations on the other as the latter go ahead with their plans to build huge dams to meet Brazil's energy needs. The BBC's South America correspondent Wyre Davies has been to see what is set to become the world's fourth largest dam, already under construction, and the indigenous area next in line for development.

From the heart of the planet's greatest rainforest one of the world's biggest civil engineering projects is emerging.

The Belo Monte hydroelectric dam is a monolithic monument to progress.

When its 18 huge turbines are fully operational, its electricity-generating capacity will make it the world's fourth largest dam, capable of generating 11,000 MW of energy.

At an estimated cost of $18bn (£15bn) the huge structure has been mired in controversy amid evidence of corruption and collusion between some of Brazil's biggest construction companies and the government.

The complex, which consists of the main generating plant and a huge separate barrage, partially blocks the Xingu River, a major Amazon tributary.

It also required the building of a new canal, to redirect and channel the flow of water, and has flooded thousands of acres of rainforest.

Human cost

There is a human cost too. The traditional local fishing industry has been decimated and thousands of riverside dwellers, called ribeirinhos, have lost their land and their livelihoods.

Many of these people, who are not members of indigenous tribes but Portuguese-speaking river dwellers, have now been forced into a completely alien urban environment.

Many we spoke to said they were not even recognised or compensated by the government and the consortium that is building Belo Monte.

"It makes us angry," says Gilmar Gomes, showing us his now worthless fishing licence.

"We see these big corporations making millions from what used to be ours and we can't even use the river anymore," he says.

Gilmar da Silva Gomes, a Ribeirinho fisherman, says his livelihood has been ruined

Building the dam brought hundreds of temporary jobs to the riverside town of Altamira but it also led to increasing deforestation and the permanent loss of many low-lying islands.

Previously shallow parts of the river, that ebbed and flowed with the rainy and dry seasons, are now 20m (66ft) to 30m under a permanent lake.

Supporters of hydro power admit mistakes were made and that in the commissioning and building of Belo Monte the government and the consortium at times rode roughshod over people's concerns.

'For the greater good'

But their position is that the rivers and their energy are there to be harnessed for the greater good of Brazil.

Low-lying land has been flooded

Luiz Augusto Barroso is the President of EPE, the Brazilian government's energy planning agency.

He advocates a mixed energy "matrix" and points out that Brazil has never been as dependent on fossil fuels as other developing countries like China or India have.

"I would definitely defend [hydroelectricity]. I think it makes sense for the country and it's a resource that benefits society and we should be properly informed about the alternatives before we consider not going ahead with these projects," says Mr Barroso.

"Let's not forget that in the developed world almost 70% of the hydro potential has already been exploited, whereas here in Brazil, 70% of our hydro has not been explored yet," he adds.

Those living at the river's edge fear for their future

Successive Brazilian governments, both on the left and the right of the political spectrum, have claimed to be fully committed to cutting their carbon footprints as part of the Paris Agreements on Climate Change.

That includes a commitment to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 37% by 2025.

But environmentalists say that Brazil's heavy reliance on hydroelectric power means the sector has a far greater carbon impact, through rotting vegetation, flooded forests and the physical impact of dam construction, than the government cares to admit.

Next in line?

Mr Barroso is cautious about giving the number of dams that might eventually be built in the Amazon, especially big costly mega-projects like Belo Monte.

But as many as 100 hydroelectric projects were envisaged in the government's National Energy Plan.

While going a long way to meeting Brazil's future energy needs, the construction of so many structures on the world's greatest river system would have a huge impact on the environment and its people.

Next in line for development is the Tapajos, described as the most beautiful river in the Amazon region and home to the Munduruku indigenous people.

A plan to build several dams along its length would transform this wide shallow river into a navigable water highway.

That would allow large vessels to transport huge cargoes of soya and other bulk commercial goods all the way from southern and central Brazil up to the Amazon and on to the Atlantic for export.

Such a dramatic transformation of the Tapajos would flood forests and islands that have been used by the Munduruku for centuries.

New battleground

Tribal chiefs say the land is legally theirs and they will forcefully resist any attempts to build dams on the river.

Wyre Davies explores an island that will be flooded if a new dam is built

"I've seen these so-called developments, the dams and the barrages. They don't bring any benefits to the people, that why we're against them," Cacique (Chief) Juarez Munduruku tells me.

Cacique Juarez Munduruku says dams have not brought any good to the locals

The chief, in a red-feathered tribal headdress, had taken me to the edge of the tribe's territory, the latest battleground between the would-be developers and Brazil's indigenous people.

"The government always comes here with its lies. There's not one place where a dam has been built that has turned out good for locals and for our tribes, there's only misery and complaints."

A recent decision by Brazil's main environmental protection agency, Ibama, to cancel a licence for one of the main Tapajos dams was seen as a major victory for the Munduruku and their supporters.

It was a vindication of their meticulous campaign to prove that land which would have been flooded by the proposed Sao Luis dam legally belonged to the tribe and could not be developed under federal laws protecting indigenous territory.

Backlash

But these painted and tattooed warriors of the Amazon are taking on powerful business and political interests.

Legislation is already being debated in the Brazilian congress which would weaken existing environmental laws and to slash funding for environmental protection agencies including Ibama.

It would also make it easier in future to force through controversial development projects and overturn those that had been denied or held up on grounds of environmental concern.

Ornithologist Luciano Naka says some key environments will disappear from the region because of the dams

Brazil's political and economic crisis may have temporarily put the brakes on the country's race to exploit its hydro potential.

Given the high cost of construction and the physical impact of building such giant structures, experts are saying that a country with so much untapped solar and wind energy potential should reassess its future energy strategy.

Historical records and the accounts of early explorers describe the Munduruku as some of the fiercest and "mightiest headhunters in all of Amazonia".

The tribe is still regarded as one of the most united and uncompromised in the entire region. Men and women still refer to themselves as "warriors".

Several of the proposed new dams along the Tapajos and its tributaries, including the Teles Pires, are already under construction and the Munduruku say that, yet again, their people are fighting to save their way of life and their identity.

As the sun sets over the upper Tapajos, its mid-river islands and the villages of its native people, a decisive battle is under way over whether to exploit or to protect this unique piece of the Amazon.

- Published17 June 2015

- Published3 December 2014