Trump's Ford deal dashes Mexican villagers' dreams

- Published

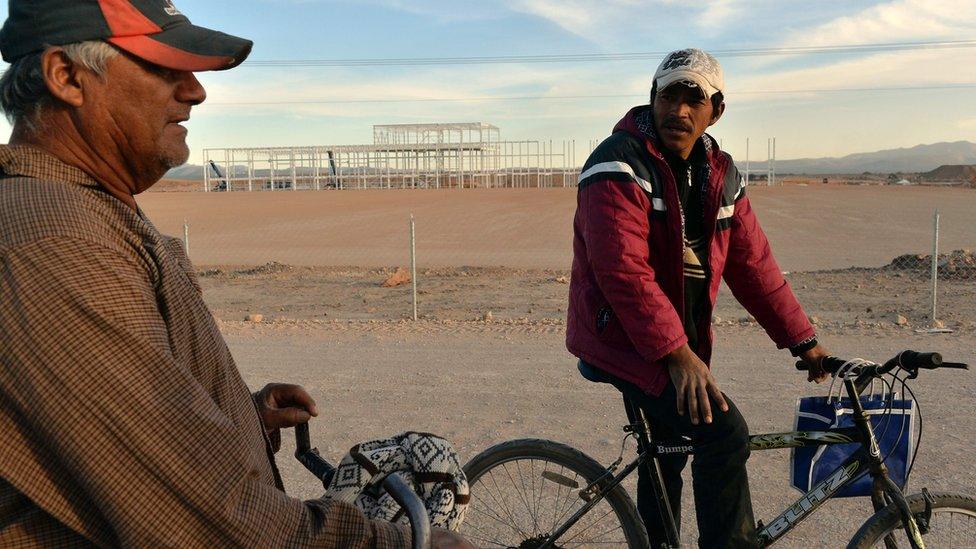

Jesus Oliva lost his job when Ford pulled out of Mexico in favour of the US

The arid desert landscape of Villa de Reyes is a world away from the glitz of the presidential inauguration on Capitol Hill.

Yet since Donald Trump was elected, the sparsely populated communities and dry valleys of Central Mexico have been inexorably linked to events in Washington DC.

Like so much with President-elect Trump, it began with a tweet.

"Make in U.S.A. or pay big border tax!" he tweeted at General Motors earlier this month.

The warning may have been aimed at GM but within hours, Ford, which had also been singled out for criticism during his campaign announced that it was withdrawing from a $1.6bn (£1.3bn) car assembly plant in Villa de Reyes.

Some of that money would be reinvested in Michigan in what the CEO of Ford described to the BBC as "a vote of confidence" in Mr Trump's business policies.

Donald Trump has promised to punish companies who put their factories in other countries

Today, that half-finished factory sits idle, gathering dust in the desert. The car plant has gone from a shining example of cross-border free trade to an eerie monument to Mr Trump's aggressive brand of economic protectionism.

Trump supporters heralded the move as evidence that his harder stance towards Mexico will boost US jobs.

'We need jobs to live honestly'

For Jesus Oliva, though, it was just evidence that the next four years will be tougher than he'd hoped. He had worked on the site for six months when the entire workforce was told they were fired one morning.

"It was a decent job," he says of his time as a night-watchman. "It was nearby so we could walk to work."

Jesus lives in the shadow of the abandoned Ford construction, in a community of around 500 families called La Presita.

Plus, of course, it was regular pay.

The factory now sits half-built and abandoned

Jesus now harvests cactus to make a living from selling a fermented alcoholic beverage called aguamiel and a typical Mexican food, nopales. At 58, he has few other options, but he fears for the younger generation.

"Many will immigrate north or go to other places to try to build their lives. We need jobs here too so people can live honestly. I think that's where the delinquency and crime comes from - having no work."

The state authorities in San Luis Potosi admit that Ford's decision was "not good news".

"It was very good news nine months ago when we signed the agreement and announced that Ford was coming to San Luis Potosi," said Gustavo Puente Orozco, the state's secretary for economic development.

Still he refrains from criticising the company - at least in public.

Gustavo Puente Orozco, the state's secretary for economic development, has not criticised Ford for its decision

"Beyond being disappointed, I have to be very professional and I have to respect what the companies do and the decisions they make. As a former businessman I understand that markets and strategies can change."

"We have to work with them to find the best solution for both parties," he adds, before underlining that Ford have not pulled out of Mexico altogether.

Far from it, in fact.

Keeping positive

Their assembly plant in Hermosillo could even end up benefitting from these international movements of investment and capital that have accompanied Mr Trump's arrival in the White House.

The local authorities insist that San Luis Potosi is still in good shape, with or without Ford, ranking fifth out of 32 states in terms of GDP growth per capita.

"We grew 5.4% in 2015 compared to the Mexican average of 2.5," said Mr Puente, which he attributes to a range of industries from mining to food production.

Nevertheless there are likely to be complications ahead.

Ford's chief executive says the move was a "vote of confidence" in Trump

One of Mr Trump's key election promises was to renegotiate the North American Free Trade Agreement, or Nafta. Added to that is the thorny question of more walls - both "real and through taxes" as Secretary Puente puts it.

As the Trump administration prepares to take office, the idea that Mexico will pay for an extended border wall is roundly dismissed by ordinary Mexicans and politicians alike.

"Mexico isn't going to pay for that wall. Not today, not ever, not even on credit," Senator Luis Humberto Fernandez said in a statement in the final days before Mr Trump's inauguration.

Still, in San Luis Potosi, many fear the worst from the incoming administration. Among them is the community leader at La Presita - an aged rancher called Gregorio Flores, known locally as Don Goyo.

People here are fearful of a Trump presidency

He can see the empty structure from his patch of land as he feeds his pigs every morning.

"We'd hoped to build a school and we urgently need a road as we're so cut off," he says, lamenting the loss for the village.

His neighbour, Jesus Oliva, perhaps one of the first casualties in a US trade conflict with Mexico, says he'd urge the president-elect to "play fair".

"They accuse Mexicans of taking their jobs. But now they're coming in and taking away ours."