Breaking barriers: The female mountain guide battling machismo

- Published

Juliana García passed her exam on the Antisana volcano

It is just a little metal pin, but for Juliana García its significance is as great as the tallest mountain.

It shows that the bearer has been internationally certified to guide tourists on mountains all around the world.

It was awarded to the 32-year old Ecuadorean on Friday, making her the first female mountain guide in Latin America to be officially certified by the International Federation of Mountain Guides Associations (IFMGA).

Juliana García is proud of the pin which shows she is an officially certified mountain guide

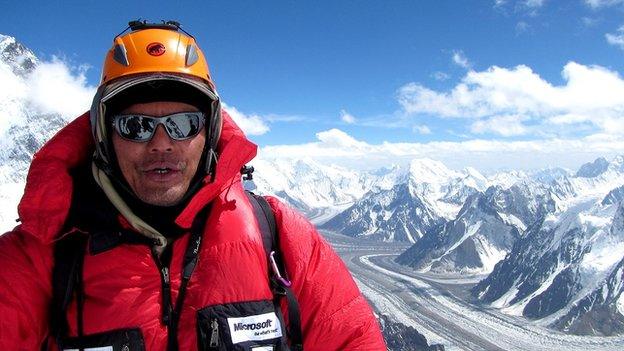

She had to demonstrate her skill on the slopes of the Antisana

Part of the exam took place on the glacier of the 5,758m-high Antisana volcano, south-east of the capital, Quito.

Under the scrutiny of national and international instructors, Juliana García and six male fellow mountaineers had to show their skills using ropes, crampons and ice axes, and demonstrate their capability to self-rescue.

Male terrain

Ever since she started practising mountaineering as a young teenager, Juliana García has been stepping onto what in Latin America and also the rest of the world is still widely considered a male terrain.

Juliana García says her path has not been easy

Years ago she attended a course at an international guiding school in Bolivia, but failed the IFMGA exam at the end of it.

She witnessed a strong culture of machismo among the instructors and her fellow students.

Laughing, she recalls how the month-long experience almost made her give up on her great dream of becoming an officially certified mountain guide.

But she persevered and in 2015 became the president of the Ecuadorean Mountain Guide Association.

As one of only two women in the world - the other is from the US - to lead a mountain guide association, she has won the respect of fellow mountaineers.

"I'm so proud to be a part of an association that has a woman representing us at the international assembly," says Joshua Jarrín, technical director of the guide school in Ecuador.

'Women aren't trusted'

But for Juliana García that distinction was not enough and she set out again to try to get the mountain guide certificate.

Juliana García did not give up after failing the exam the first time

She found that the machismo in her homeland of Ecuador was just as strong as what she had encountered years previously in Bolivia.

"It is difficult in a society that has never trusted women to do such work," she says.

The job carries great responsibility as climbers trust guides with their lives. If a climber falls, it is the guide's job to stop that fall.

Decisions taken by the guide - for instance judging the weather and snow conditions - can determine whether the party gets safely down the mountain.

In some cases women are more cautious when making these decisions.

"Some clients have told me to my face that they don't trust female guides."

The number of female mountain guides is low in other countries, too

Since she passed the exam, many of her colleagues have come out to say how proud they are of her achievement, and not just in her native Ecuador.

Francois Marsigny is in charge of the alpinism department at France's National School of Alpinism and Ski.

He thinks it is "very important" that more women follow in Juliana García's footsteps.

Juliana García hopes others will follow in her footsteps

"Women bring new attitudes to the job such as communication, client care and risk management," he says.

Mr Marsigny wants to drive up the percentage of female guides in France from its current 2% to at least 10% over the next five years.

That is a figure which in Ecuador still seems far off but Juliana García's passion for making mountaineering accessible to everyone regardless of gender is overriding.

"It's not about what's possible or not. The mountains are for everyone," she says.

- Published12 September 2016

- Published21 November 2015

- Published12 July 2015