Venezuela's irreconcilable visions for the future

- Published

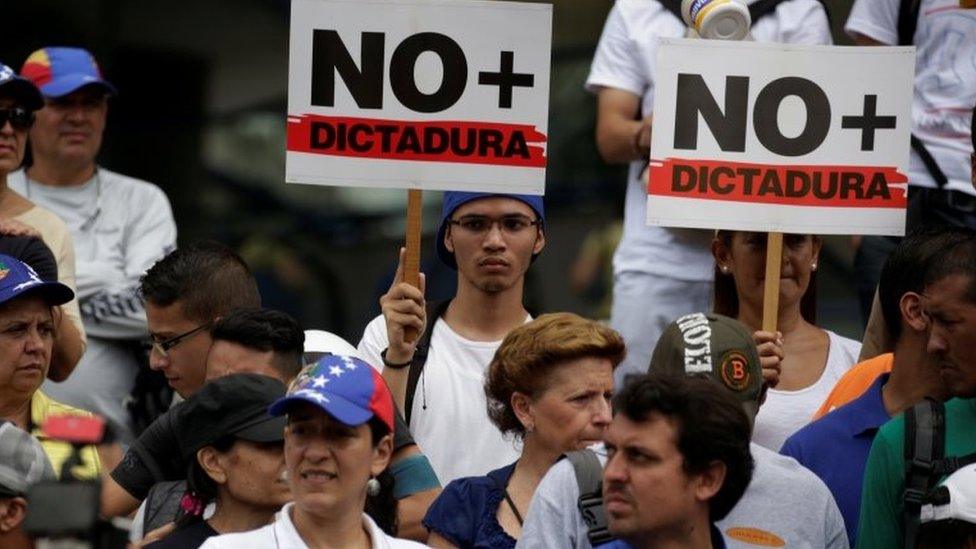

Signs reading "No more dictatorship" are a common sight at anti-government protests

"Venezuela is now a dictatorship," says Luis Ugalde, a Spanish-born Jesuit priest who during his 60 years living in Venezuela has become one of the South American nation's most well-known political scientists.

A former rector of the Andres Bello Catholic University in Caracas, Mr Ugalde does not mince his words.

He compares Venezuela to an ailing patient who is on the brink of being killed off by well-meaning but incompetent doctors.

Venezuela's problems are not new, he says. At their heart is the mistaken belief that it is a rich country.

He argues that while it may have the world's largest proven oil reserves, Venezuela should be considered overwhelmingly poor because it hardly produces anything except oil.

The curse of oil

A lack of investment in anything but the booming oil industry in the 20th Century meant that its human talent was never really fostered and its economy never diversified, resulting in an absolute reliance on imports.

Venezuela's late leader, Hugo Chávez, further compounded the illusion of Venezuela's wealth to the detriment of the country, Mr Ugalde argues.

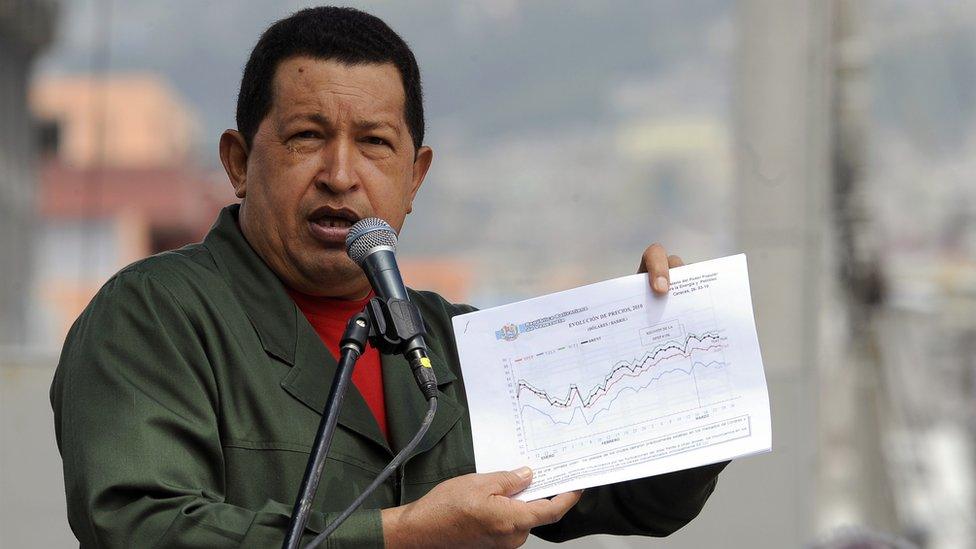

While oil prices were high, Hugo Chavez could afford to fund social programmes

"He told the Venezuelan people that there were three things standing between them and prosperity: the US empire, the rich and the entrenched political elite, and that he would deal with all three so that the people could enjoy Venezuela's wealth."

Investing Venezuela's oil revenue in generous social programmes, building homes and health care centres, expanding educational opportunities and providing the poorest with benefits they did not previously have, gave the government of President Chavez a wide support base.

But with falling global oil prices, government coffers soon emptied and investment in social programmes dwindled.

The death from cancer of President Chávez in 2013 further hit the governing socialist PSUV party hard.

His successor in office, Nicolas Maduro, lacked not only the charisma of President Chávez but also his unifying presence at the top of the party and the country.

Mr Ugalde does not doubt that President Maduro came to power democratically in 2013.

Luis Ugalde says that Venezuela has become a dictatorship

But he argues that what he has done since - such as undermining Venezuela's separation of powers - has turned him into a dictator.

The Democratic Unity Roundtable opposition coalition won a landslide in the December 2015 election and yet it has seen almost all of its decisions overturned by the Supreme Court, a body which opposition politicians say is stacked with government loyalists.

An attempt by opposition politicians to organise a recall referendum to oust President Maduro from power was thwarted at every step by Venezuela's electoral council, another body opposition politicians say is dominated by supporters of Mr Maduro.

'Final straw'

But for many the final straw came on 29 March 2017, when Supreme Court judges issued a ruling stripping the National Assembly of its powers and transferring those powers to the court.

The opposition-controlled National Assembly is overlooked by a poster of Hugo Chávez

While the Supreme Court suspended the most controversial paragraphs just three days later, the ruling managed to unite the hitherto divided opposition and spur them into action.

There have been almost daily protests and more than 45 people have been killed in protest-related violence.

While many of those protesting against the government share Mr Ugalde's view, the government is adamant it is defending democracy in Venezuela.

It argues that the National Assembly was in contempt when it swore in three lawmakers suspected of having been elected fraudulently and that all of the decisions made by the legislative body since then are therefore invalid.

New constitution call

The government has responded to the most recent wave of protests by calling for a constituent assembly.

Drawing up a new constitution will bring together the people of Venezuela and create peace where there is now unrest, President Maduro argues.

He also says he wants to enshrine some of the social programmes created by the socialist government in the new constitution.

At a pro-government rally, a sergeant in the National Bolivarian Militia, a body created by the late President Hugo Chavez, says he whole-heartedly backs the idea.

Gerardo Barahona says he supports President Maduro's plans for a constituent assembly

"We're against terrorism, those people protesting violently who're burning buses, we support the constituent assembly," Gerardo Barahona says.

Marta Elena Flores, 60, says the opposition is "out to wreck everything" achieved under the socialist government.

"We need to protect all the benefits the government has given to the people," she says.

"We need to enshrine them in the constitution so that the opposition doesn't even have the chance to rob us of them."

Marta Elena Flores says the government's social programmes have made a difference to her life

"I personally have been able to have two operations thanks to the government's medical programmes. The opposition begrudges us those benefits."

Opposition politicians have been dismissive of the president's call for a constituent assembly, saying it is a ruse to delay overdue regional elections and further strengthen the power of President Maduro.

Representatives of the major opposition parties declined a government invitation to discuss the creation of the assembly and, three weeks after the idea was first mooted by President Maduro, little progress has been made.

Government critics say the constituent assembly is "a fraud"

Previous attempts at dialogue backed by former international leaders and even the Vatican have failed.

Anti-government marches meanwhile have been spreading throughout the country and clashes between protesters and the security forces have become more frequent and the number of dead has been on the rise.

Those opposed to the government say they are determined to keep the protests going until fresh general elections are called and the government is ousted.

Some analysts have said that what it will take for the government to fall is for the protests to spread to the "barrios", the poor neighbourhoods which have been the support base of the governing socialist party.

Miguel Pizarro, an opposition lawmaker who represents the barrio of Petare, one of the poorest in Caracas, dismisses that argument.

Miguel Pizarro is proud to represent Petare

"The only contact people who make that argument have with the barrio is through their cleaning lady," he says.

"There has been resistance to the government in the barrios for a long time, that is how I got elected!"

Others think that it will take the military to switch sides for the government to be ousted.

But with Defence Minister Vladimir Padrino taking to Twitter on 20 May, external to accuse protesters of fomenting anarchy and international organisations of being "immoral accomplices who don't denounce the violence" there is little sign of that happening any time soon, at least within the highest ranks.

In the short term at least, there seems little chance of the current deadlock in Venezuela being broken and every likelihood that the crisis will worsen.