Mexico students: Pegasus spyware 'used on foreign investigators'

- Published

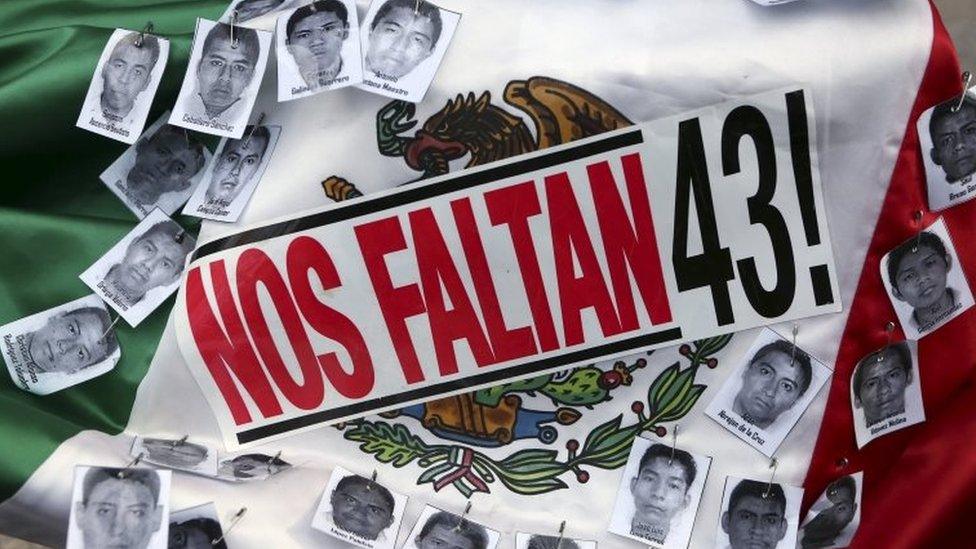

A march in Mexico City in June marking the 33rd month since the 43 students disappeared

International experts investigating the suspected abduction and murder of 43 students in Mexico three years ago were targeted with government spyware, an internet watchdog says.

The Israeli-made spyware was only sold to governments, according to Citizen Lab, which is based in Canada.

Mexican journalists, human rights activists and opposition politicians have made similar allegations.

Mexico's government denies using the spyware to snoop on its opponents.

It says it has only used intelligence tools in the interest of national security or to fight organised crime.

The students, from an all-male college in the southern town of Ayotzinapa, were declared dead after disappearing in 2014 in the south-western state of Guerrero.

Their relatives have accused the authorities of a cover-up. Some Mexicans have held out hope that members of the group may yet be found alive.

Who are the latest alleged targets?

The foreign experts, convened by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, were called in to investigate the disappearance of the students.

The team has repeatedly accused the Mexican government of blocking their work.

Citizen Lab, which is based at the University of Toronto, says in its analysis, external that it has found forensic evidence to show that the investigators' mobile phones were being targeted by Israeli-made spyware.

One member, Spanish investigator Carlos Beristain, said the attempt to install spyware could be a "more serious crime given the diplomatic protected status" the group held.

Attempts to infect their devices reportedly took place in March 2016, shortly after the group accused the Mexican government of hampering its inquiry, and as they were preparing a final report.

How does the spyware work?

The software, known as Pegasus, was sold to Mexican federal agencies by the Israeli company NSO Group on the condition that it only be used to investigate criminals and terrorists.

It is usually sent in a text message to a smartphone.

If the person taps on it, the spyware is installed, and huge amounts of private data - including text messages, photos, emails, location data, the device's microphone and camera - are hacked.

Mexican journalist Carmen Aristegui is another alleged target; she says her investigative team and under-age son also received messages

One message sent to investigators in March was from someone pretending to pass on personal information about a funeral. "Here are the details. I hope you can come," it read.

According to the New York Times, external, the same link was sent last year to an academic trying to impose a sugar tax in Mexico and, in that case, the message was confirmed as a Pegasus trick.

Mr Beristain said he had received the message but had not opened it as he suspected some form of espionage.

Who are the missing students'?

On the evening of 26 September 2014, a group of 43 Mexican students disappeared in Guerrero.

They had been studying at an all-male teacher training college that has a history of left-wing activism.

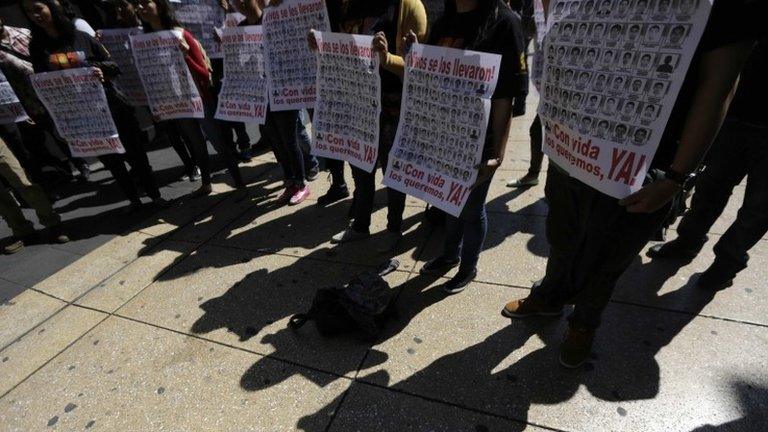

Relatives and activists holding up portraits of the missing at one of the many protests

Before they disappeared, the students reportedly clashed with municipal police while on their way to a protest. Police opened fire on their buses.

According to the official government report, the group was then handed over by corrupt officers to members of a local drugs gang.

The government version of events says their bodies were burnt in a fire at a rubbish dump. Authorities identified one student, Alexander Mora, from charred bone they said they had found at the site, and they partially identified another.

The international investigators have disputed the fire theory, saying they have yet to find sufficient evidence.

The Mexican attorney general has declared them all dead but their relatives still want proof of what happened that night, and justice.

The case is so well known in the country and across Latin America that the students are widely known simply as "The 43".

- Published27 February 2015

- Published29 June 2017

- Published20 June 2017

- Published25 August 2022