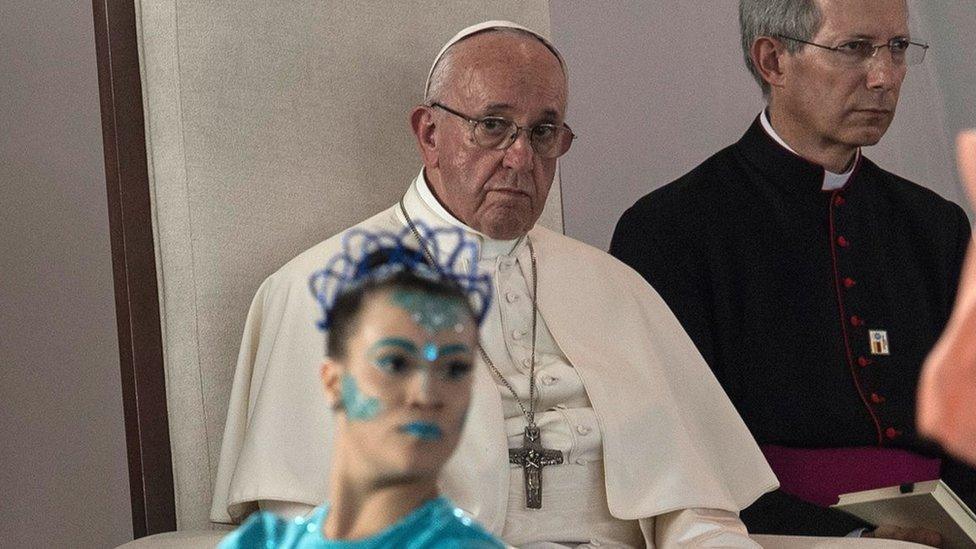

Victims and perpetrators gather for Pope's Colombia visit

- Published

Villavicencio was full of Pope memorabilia during Francis' visit

Pope Francis is the most illustrious visitor to have ever visited the city of Villavicencio.

In the main square, the excitement was clear to see.

Dotted along the side of the square, in front of the cathedral, dozens of stalls were selling Pope memorabilia.

From T-shirts to key rings; special edition coins to plastic ponchos, people wanted a piece of him to take home.

"I'm so happy he's come," says 22-year-old Mauricio Rodriguez. "He needs to come more often, he drove past far too quickly."

Villavicencio was chosen as part of the pontiff's Colombia tour because it was at the heart of the conflict that this country faced for more than five decades.

Villavicencio has been scarred by the conflict - but is now trying to recover

"Every day, there would be a new story in the papers: a local town being taken over, a mine, a mass kidnapping or extortion," says Villavicencio's Mayor Wilmar Barbosa, who admits that his generation knows nothing else.

"It's a city of 500,000 people, and 146,000 are registered with the victims' office - that's more than a quarter of the population who've been victims of the armed conflict," he says.

"After the signing of the peace deal, that encouraged us to not just reconcile but to pull ourselves together."

'What happened to my dad?'

Reconciliation has been the theme of the Pope's visit, and Villavicencio was seen as the pinnacle of his tour.

The open-air mass in the morning felt like a music concert. Cheering, singing and excitement. People had their mobile phones out, recording it all to capture this moment.

Virginia Bermudez says she has "lots of hope for the peace process"

Virginia Bermudez was one of about 5,000 victims who were invited to a prayer event with the Pope.

Perpetrators of the violence were also present in the ceremony preaching forgiveness.

Virginia's mother was enlisted into the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Farc) when Virginia was six.

She tells me she sacrificed herself because the Farc threatened to take Virginia and her siblings. Then 13 years later, Virginia's father was disappeared by the group too.

She's given up expecting her mother to return. Part of Virginia feels her mother didn't want to come back. But she's not giving up on her father.

"I've got lots of hope for the peace process - people call me a dreamer," she says.

"I want to know what happened to my dad. Where's his body? Is he dead? If he's alive, do they have him?"

She thinks the peace process means she could get answers to those questions.

Window-dressing

Sat next to her is another victim, Luz Angela Giraldo Serrato.

Farc guerrillas took over her family's cattle farm in Miraflores, in the state of Guaviare. Her step-father and brother were killed because the family didn't pay bribes in time.

Luz Angela Giraldo Serrato says nothing has changed since the peace process

Luz was studying in Bogota at the time - but lack of finances meant she had to stop. Her family moved from city to city, trying to escape the Farc who were chasing them for the farm's documents.

"Nothing's changed since the peace process," says Luz. In the neighbourhood she now lives in, many still face extortion.

"I think the process is window-dressing," she adds.

Luz and Virginia highlight the challenge facing Colombia.

Everyone wants peace, but people are divided as to how best to achieve it.

The Pope's message here was that reconciliation was the only way to ensure the success of the peace process.

He told Colombians to rise from the "swamp" of bitterness.

Easier said than done after half a century of conflict.

Johana Jimenez sees herself as both a victim and a perpetrator

But 37-year-old Johana Jimenez says Colombians have to work at it.

Johana runs a little beauty parlour on the outskirts of Villavicencio. A simple salon with a mirror, a hairdressing chair and a row of bright coloured nail polish bottles on a shelf.

Johana was given eight million pesos (£2,090; $2,760) by the government to help her get her business off the ground.

It was a grant aimed at reintegrating former fighters because up until a few years ago, she was a Farc member.

When her 12-year-old sister decided to sign up, she said she had little choice but to join too, to protect her.

To do that, she had to leave her two daughters with her parents-in-law.

"I had to make a decision. My sister needed me at the time," she tells me. "My daughters had stability, they had someone to look after them."

New beginning

Nearly four years later, they escaped and sought refuge in a church.

The priest handed them over to the army and from there, she was integrated back into society. But two of her sisters have died.

"I am a victim but I am also a perpetrator - so I'm in both camps," she says of the divisions in Colombia.

"I want the Pope's message of peace to lead to less judgement and more understanding about people who used to be guerrillas or paramilitaries."

She tells the story of some boys who found their mother mutilated by paramilitaries. They joined up with the Farc to take revenge.

"These people were angry," she says. But the boys are now part of the 7,000 former fighters who are being reintegrated back into society.

The deal struck between the government and the Farc last year made this possible, so Johana backs it, despite having reservations at first.

"It's the best way of achieving peace."

- Published8 September 2017

- Published7 September 2017

- Published6 September 2017

- Published6 September 2017

- Published28 October 2022