How Chilean fishermen adapted to protect marine life

- Published

Mr Vergara says things have changed on Isla Choros since it became part of a national reserve

Chile created one of the world's largest marine protection areas earlier this month off the coast of Easter Island after the indigenous Rapa Nui population voted in favour of the scheme. Before their vote, a delegation from Easter Island visited Punta de Choros on the Chilean mainland. As Jane Chambers reports, the fishing village is a pioneer in diversification.

"We used to camp on Isla Choros, because it was the best place to dive for locos [Chilean abalone]," Salvador Vergara says about the island just off the Chilean coast from where he lives.

The locos he talks about are large edible sea snails, a highly sought after delicacy in Chile which also fetches high prices at seafood markets in Japan.

"We even had a football pitch, but now only scientists and park rangers can go there," he recalls.

Salvador Vergara is a third-generation Chilean fisherman.

The fishing village of Punta de Choros where he lives is located in one of the world's biodiversity hotspots. The coastal waters are home to blue whales, 80% of the Humboldt penguin population, bottlenose dolphins and countless seabirds.

The fishermen now use their colourful boats to ferry tourists around the islands

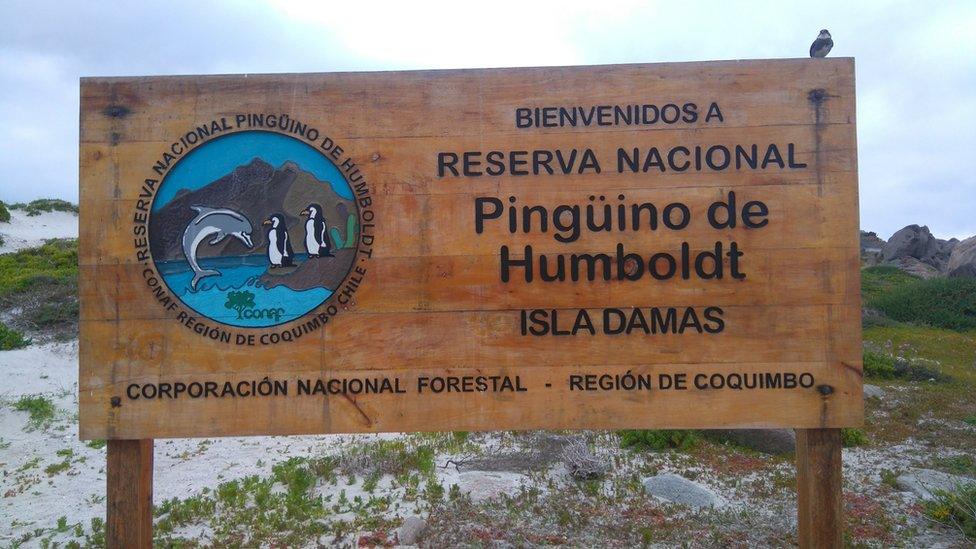

The three nearby islands of Choros, Damas and Chañaral were declared a national reserve in 1990 and named Humboldt Penguin National Reserve after their most famous residents.

Much of the surrounding area is a marine reserve.

Local fishermen are only allowed to dive for locos and other seafood at certain times of the year and have to have licences to be allowed to fish for their allotted quota.

The Humboldt National Reserve was created in 1990

Faced with these restrictions, the local fishing community has had to look for alternative ways to make a living during the times when they are not allowed to fish or dive for seafood.

Mr Vergara and other fishermen are part of a collective which owns sixty boats. For $12 (£9) they take tourists on a tour around the islands.

Dressed in orange lifejackets tourists ooh and aah at bottlenose dolphins jumping alongside the boat in the choppy dark blue waters. If they are very lucky, they might even spot a blue whale, the largest mammal on earth.

But the little Humboldt penguins are the star attraction.

Humboldt penguins breed in coastal Peru and Chile

They are named after the cold Humboldt Current which runs from the Island of Chiloe in the south of Chile all the way up to Peru and provides an abundance of krill for the penguins.

Guilty secret

Mr Vergara is passionate about nature. His eagle eyes spot plump brown sea lions feeding their babies, sea otters slithering across the rocks in search of penguin eggs and sleek black cormorants diving from the grey rocky cliffs.

But he has a guilty secret. He says he and his fishermen friends were not always as careful around the area's wildlife as they are now.

"Humboldt penguins get stressed quite easily," he explains.

"When we used to camp on Isla Choros, they would get frightened and run away from us. Sometimes they would even jump off the cliffs to their death."

Mr Vergara has also eaten penguin. "My father was also a fisherman and when penguins got trapped in the fishing nets he cooked them with onions," he says.

"They have black meat. At first I thought they were delicious, but then I got ill and of course now I would never eat one!"

Eco-tourism is not the only business the fishermen have become involved in. A group of them has also set up a small seafood processing plant in the village where they pre-cook and freeze crab claws.

The seafood processing plant is providing jobs to locals

"It's much better now we are running our own plant. We can add value to the product and sell it at a better price to our market in the United States," explains one of the owners, Oscar Aviléz.

Many of the local fishing villages have also opened small restaurants.

"We began cooking out of necessity," explains Doña Juanita who owns a restaurant in a village called Caleta San Pedro.

Doña Juanita started by selling homemade food at the markets and now she owns a restaurant

"Our husbands are saltwater clam collectors and the beach that we have just outside this restaurant had lots of clams," she says.

But Doña Juanita says that because too many have been collected, they have disappeared altogether. "So we had to stop being house wives and go out to work" she says.

She and other fishermen's wives began by selling their homemade specialities such as clams with parmesan cheese and empanadas (pasties) at the local market.

Their food proved so popular they earned enough money to open their restaurant in a bright, spacious building on the clam beach.

'Tough at first'

She says it was not an easy transition for the women to make, especially not for their husbands. "They didn't like us being out at work, but now they are proud of us," she says.

The food on offer at the restaurant is simple but locals say it is both good and cheap

"It was tough at first to leave our children at home and work such long hours. But now we make more money than they [our husbands] do."

Mr Aviléz agrees with Doña Juanita that life in the fishing communities has improved since they started diversifying.

"We want to make this work for future generations," he says. "Our children need to be able to make a living from the sea, just like we have. But one needs to learn how to treat it properly as a resource.

"We have had to learn to live in harmony with the sea," he says.

- Published22 August 2017

- Published16 March 2017

- Published23 January 2016

- Published5 October 2015