Why donkeys are a reminder of one island's 'sweet' old days

- Published

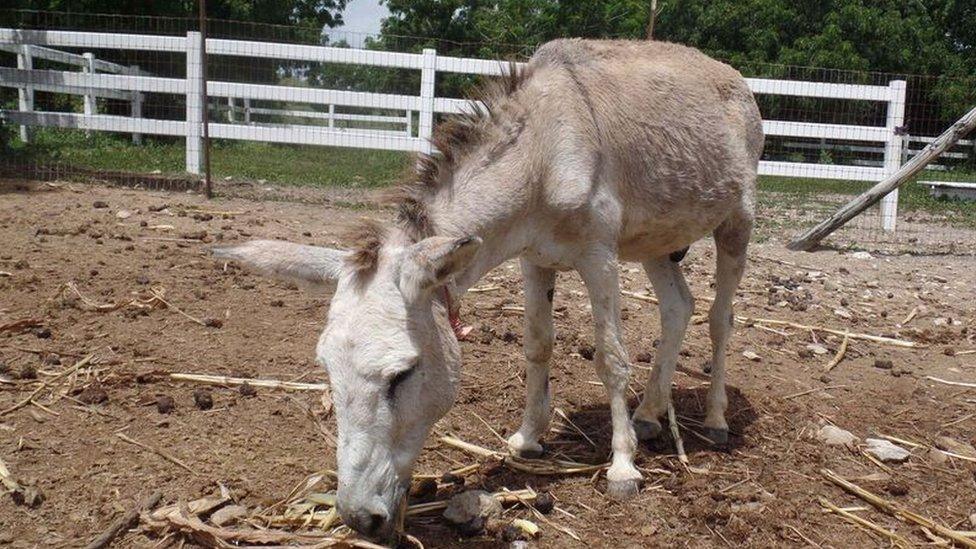

The sanctuary in the town of Bethesda has become home to 150 donkeys

Early morning visitors meander around the Vivian Richards stadium in Antigua.

But none though, as you might expect, are dressed in white and brandish cricket gear.

In fact, the pastoral surrounds of the legendary cricketer's eponymous venue are a popular hangout for the island's donkeys too.

Once the lifeblood of the sugar industry, these gentle equines helped put the Caribbean country on the map well before the "Master Blaster".

Donkeys are a common sight in Antigua

It is not just outdoor arenas they like. They can also be seen careering through crops, gate-crashing gardens, or just plodding serenely along roads in their constant hunt for food.

The decline of the sugar industry, and increase in modern transportation, may have rendered Antigua's donkeys redundant but that has done little to curtail their population.

While some continued to be used on farms and to lug produce to and from market, they were largely left to fend for themselves after the doors closed on the last sugar factory in the 1970s.

Today, the donkeys are one of the last vestiges of the roaring industry which helped build the British Empire, along with the dozens of centuries-old sugar mills which pepper the landscape.

Donkeys have lived on the island for centuries

These leftovers from the sweet old days have called the island home for almost 400 years, says local historian Reginald Murphy.

"Donkeys and horses would have arrived with the first English settlers in the 1630s, and were likely bred to get mules," he tells the BBC.

"They were beasts of burden, used to carry sugarcane on the plantations and they may have been used to power certain kinds of cane-crushing mills too."

Save for a minority that still use them for cheap transportation, most people have little use for donkeys these days.

"As a kid I remember people in the villages loading up their donkeys with produce from their farms and sending them back home; they knew the way all on their own," Mr Murphy recalls.

"Now everybody has a pick-up truck."

A dentist guides one of the visitors through a routine

One place the amiable creatures can find refuge is at Antigua's Donkey Sanctuary in Bethesda, external, which has become a popular tourist attraction.

The 43-acre site is home to 150 jacks, jennies and foals. Its executive director Karen Corbin estimates up to 400 more are roaming wild, breeding at will.

"They cause a lot of trouble for crops," she says. "Farmers work very hard; 10 donkeys can destroy that in minutes."

The shelter's Carol-Faye Bynoe agrees: "They also break irrigation lines, crash through people's gardens and overturn garbage bins looking for food.

"And they're smart too; they know how to turn on standpipes to get water. Unfortunately, they neglect to turn them back off again."

On top of the impact on the human populace, the vagrant lifestyle is tough for the donkeys too.

Many arrived at the sanctuary as a result of injury or mistreatment.

The donkeys offer animal therapy to visitors from local schools

"Some came in with deep lacerations from being slashed with a cutlass or a rope embedded in the neck," Ms Bynoe says.

"One had a broken hip from a car accident and one female had a severe limp from being tethered so tightly with nylon her foot was almost amputated."

Stevie, one of the sanctuary's long-term residents, is totally blind following a collision with a car.

Staffs think he may have been ridden into the capital by children.

"Kids like to ride donkeys but they can be cruel, flogging them, not hydrating them properly and tying them without shade," Ms Bynoe says.

"But Stevie copes just like a blind person; all his other senses are heightened. He's a marvel."

Donkeys can live to be as old as 50 and with each one costing $250 (£191) a year to care for, the charity-run sanctuary is under constant pressure to fundraise.

Staff at the sanctuary describe Stevie, who was left blind after a collision, as 'a marvel'

Collectively, the animals consume 750 gallons of water and a lorry-load of guinea grass every day.

One way they earn their keep is offering free "animal therapy" to visitors from local special needs schools and community groups.

To stem their numbers, male donkeys at the sanctuary are castrated from the age of three and plans are afoot to extend that to those in the wild too.

Mobile catch pens are set to be placed in the most donkey-dense areas for a castrate-and-release programme funded by UK firm Animal Friends Insurance, which recently sponsored a visit by two equine dentists.

"We can't take them all in but we need to stop the population exploding," Ms Corbin adds.

"Antigua owes a lot to its donkeys; it's only right we take care of them in return."

- Published2 October 2017

- Published25 August 2023