Argentina sub: What happens when a submarine vanishes

- Published

A search is under way for the ARA San Juan

A submarine with 44 crew on board remains missing after disappearing off the Argentine coast on 15 November.

In the last reported contact with the ARA San Juan, the sub's captain reported a breakdown relating to a "short circuit" in the sub's batteries.

On Thursday, eight days after going missing, the Argentine navy said an event consistent with an explosion was recorded near where the submarine disappeared.

Why can't subs be detected?

Submarines are built to be difficult to find. Their role is often to participate in secret surveillance operations.

Dr Robert Farley, a lecturer at the University of Kentucky who has written on the subject, says that a sub is very hard to trace if resting on the seabed because under such circumstances it will not be making any "noise".

"Noise, which would otherwise be picked up by what is known as passive sonar, is distorted and [the sub] looks - to active sonar pings - like the sea bottom," he says.

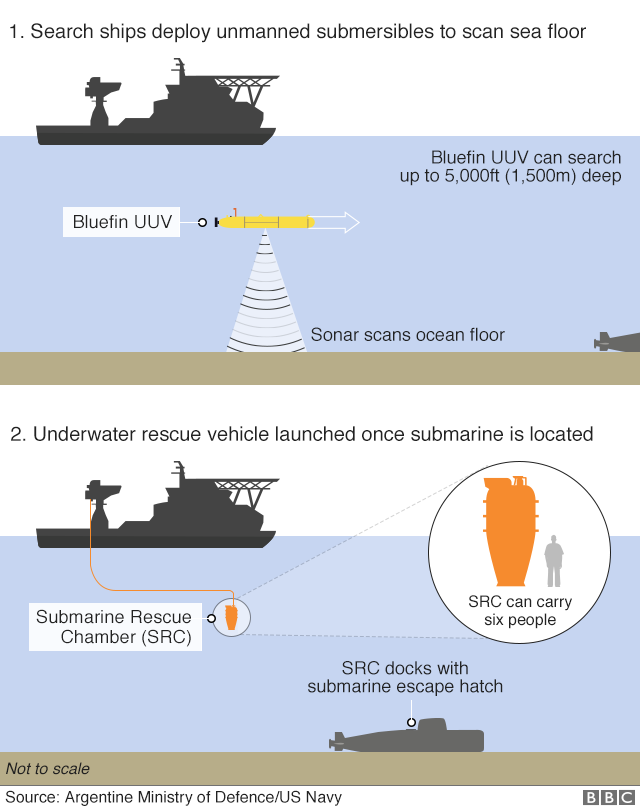

So how can subs be found?

There are a number of ways that the captain or crew can make their location known if in distress.

These methods include sending signal calls to contacts at naval bases or allied ships, or releasing a device that floats to the surface but remains attached to the submarine.

Stewart Little, a submariner with the Royal Navy for several decades who now runs the Submarine Rescue Consultancy, says that the standard searching protocols provide two phases in each hour when searching forces go silent and listen out for signals.

"Those submariners will be furiously making those signals when called to do so," he told the BBC.

What do we know about what happened?

Before the submarine went missing, the crew had reported a malfunction in the vessel's batteries caused by an intake of water through the snorkel system (by which it renews oxygen), reported Argentina's La Nacion newspaper. However, the commander reported that the problem had been resolved.

On Wednesday, the navy said there had been a loud noise detected about 30 nautical miles (60km) north of the last-known location of the submarine. A spokesman called this a "hydro-acoustic anomaly". On Thursday, the same spokesman - Capt Enrique Balbi - said there was an event consistent with an explosion nearby but the cause was not known. He called it an "abnormal, singular, short, violent, non-nuclear event" and said the search would continue in the same area.

What if it has sunk?

"If it had sunk in waters of less than about 180m (600ft) it's likely that someone would have tried to escape from the submarine," speculates Mr Little. "As that hasn't happened, it's probably in waters deeper than that.

"I'm hopeful that it's less than 600m - because that's the depth at which the assembled rescue forces are capable of operating. If they were to search at contours between 180m and 600m... that would give them the best chance of finding the submarine."

Rescuers can't reach below 600m, Mr Little said - and below that, each submarine has a "crush depth" at which point its structure will not be able to withstand the water pressure.

It is extremely rare for submarines to sink, Mr Little points out. It last happened in 2000, when the Russian submarine the Kursk sank in the Barents Sea, killing all 118 crew on board.

How long can a crew survive submerged?

The number of days that a crew can survive depends on how long they have already been performing duties underwater and how well prepared they are for losing power.

"If batteries were charged and air refreshed," Dr Farley says, "then outlook is hopeful".

In relation to the Argentine sub he adds: "Outer range appears to be 10 days if they were well prepared."

How is the crew trained for this?

One of the most important practices is for trapped crew members to slow down their breathing rates in order to conserve oxygen.

Dr Farley says that this it is a hard thing to train people to do, adding that in such circumstances: "My guess is that they would be cautioned to reduce activity and reduce speaking in order to save oxygen."

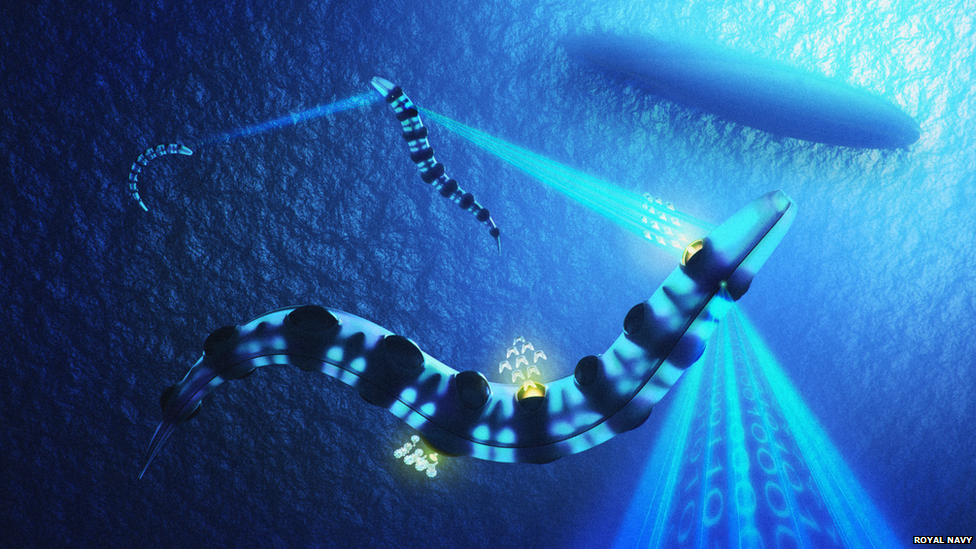

An underwater rescue module has been deployed in the hunt for the missing Argentine vessel

The conditions, likely to be cold and damp, may well have a detrimental impact on morale, but the personnel on board will be well trained and disciplined.

They will likely establish routines, making themselves as comfortable as possible while minimising their movements and supporting one another as they await rescue.

The response to these emergency incidents has also been improved at the international level since the Kursk disaster.

An organisation called the International Submarine Escape and Rescue Liaison Office, based in Northwood just outside London, co-ordinates all international response and is playing "a key role in this operation", Mr Little says.

What are the main dangers?

With a possible shortage of oxygen and a build-up of carbon monoxide, suffocation is the number one risk.

Oxygen can be supplied either through canisters or generators that perform a process called "electrolysis" - which effectively separates components such as water and oxygen. However a lack of power will hinder this process and the supply may gradually run out.

There are other dangers that could also come into play.

Dr Farley points out that if a compartment within a trapped sub becomes flooded, this can lead to "flash fires and other nastiness" as the air gets further compressed.

Is there a plan for such accidents?

In the event that a submerged vessel suffers problems in returning to the surface, procedures can be implemented to help raise it.

To control buoyancy, the fuel or ballast tanks - which can add weight - can be emptied and used to lift the sub. To achieve this, the diesel fuel or ballast is released, emptying the tanks, and the chambers are then filled with air.

Subs also have small hydroplanes; wings that are adjusted to allow water to travel in different directions as the vessel pitches its bow and stern up or down to assist its movement.

- Published21 November 2017

- Published29 August 2017