On the run: How one opposition mayor fled Venezuela

- Published

"I shaved off my beard, wore glasses and a flat cap, and they did not recognise me"

David Smolansky prepared himself for his escape. The mayor of the pretty El Hatillo neighbourhood in Caracas had been threatened with arrest for three years and he had seen other mayors detained.

So in August when he was removed from office and sentenced to 15 months in prison for failing to prevent anti-government protests, it did not come as a big surprise.

On 9 August, the day Venezuela's Supreme Court was due to hear his case, Mr Smolansky went into hiding. The mysterious disappearance of a security camera at his apartment made him suspect his time was up and authorities were closing in on him.

Rehearsing for exile

"I knew that sooner or later the dictatorship could have me arrested so I got organised," he said. None of his family knew his plans but he had done his homework.

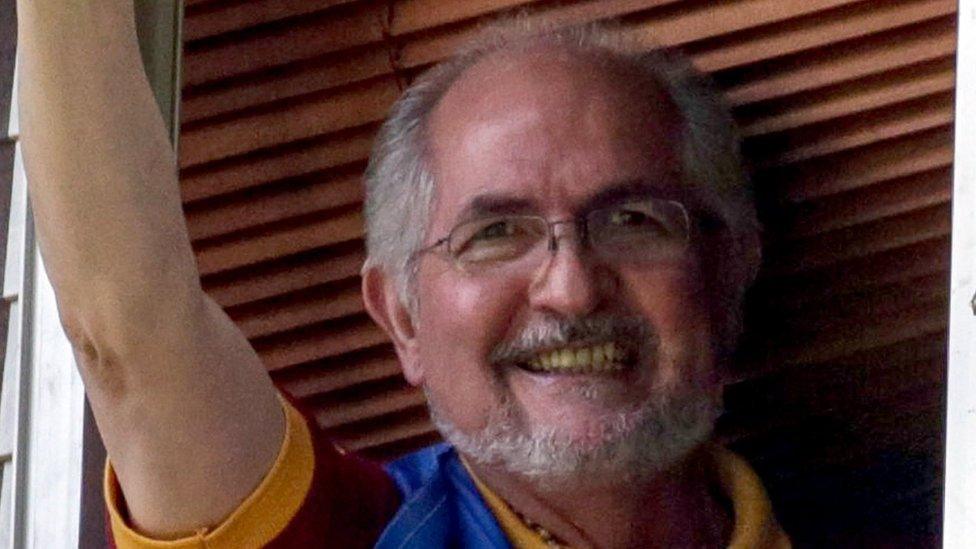

David Smolansky often spoke at opposition protests

He had rehearsed this before. His original plan had been to take a boat. During one practice run, the boat could not set sail. On another, the coastguard allowed it to sail for just 10 minutes. So he knew leaving Venezuela by sea would be impossible.

The authorities had banned him from flying so that was not an option either.

He chose not to head to Colombia because other persecuted leaders had fled the country that way.

"I thought of Brazil because it would be a surprising move for the regime," he said. "And Brazil is a strategic ally that Venezuela needs to have when we have democracy again."

So he crossed Venezuela by car, driving more than 1,200km (750 miles) to the border with Brazil.

New identity

"I shaved off my beard, wore glasses and a flat cap, and they did not recognise me," he said. He stayed in different places, across different states, all the time lying low.

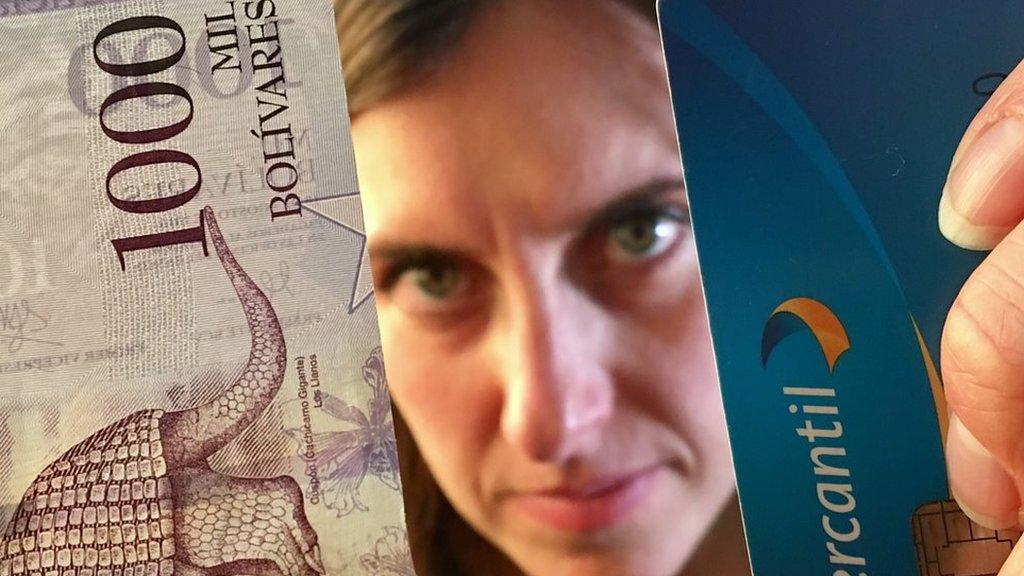

The past few months have seen a crackdown on political opponents of the government

With a new look and a Bible to give the impression he was a religious man and to avoid lots of questions, he passed through 35 checkpoints. At four of them, they checked the car.

But he said the first few hours were some of the hardest. At the first checkpoint, the soldier told him to lower the windows. There was nobody on the road, it was pitch black.

"When I planned this I had all the checkpoints on the map. But this one surprised us," he says, adding that he started off travelling with two other people. "I said we were on holiday and that we had left early to enjoy the day and avoid traffic. Then the soldier said: 'OK, you can go.' It was very tense."

Mr Smolanksy also carried false ID - something he does not feel proud about, but he said he had no option if he was ever to get out of the country.

During his 35 days in hiding, he was often on his own. He read, wrote many letters and managed to watch television from time to time. He had access to a mobile phone that the intelligence services could not trace, and at times also had access to safe internet.

He had a team who helped him but he was cautious about using them.

"They helped me with little things," he says. "Then I understood that most of the things I had to do on my own. It was the safest way to do it, not just for me, but so as not to put anyone at risk."

Eventually, on 13 September, he crossed into Brazil. Without specifying exactly where he crossed, he says he could not use an official border. When he got to the other side, the authorities were waiting for him. From there, he flew to Brasilia to meet the minister of foreign affairs.

"It was a very emotional moment for me," he says.

Political persecution

Mr Smolansky is one of several mayors to have charges levelled against them. The past few months have seen a crackdown on the government's political opponents.

"When you have hundreds of thousands of people protesting, that's what really annoys Maduro"

And the past few months have also seen several high-profile politicians flee. Most recently former Caracas mayor Antonio Ledezma fled to Spain via Colombia.

"No other authority has been more persecuted than mayors," he says. "If you represent 10 million people and those people now do not have the majority of the mayors they elected, this is very dangerous for a country, especially because local authorities are closest to people."

Does he expect to return soon?

"I have to prepare for the worst," he says. "My grandparents left the Soviet Union in 1927, my father left Cuba in 1970, so I am the third generation of Smolanskys who've have to leave a country because of a totalitarian regime."

"The difference I want to have from my father and grandfather is to go back to my country. My grandparents never went back to Kiev, where they were born. My father has not been able to go back to Havana, where he was born," he says. "But I hope I can return to Venezuela."

But he believes there is still a complicated future ahead.

"There's no guarantees right now in Venezuela to have transparent, clear and fair elections," he says.

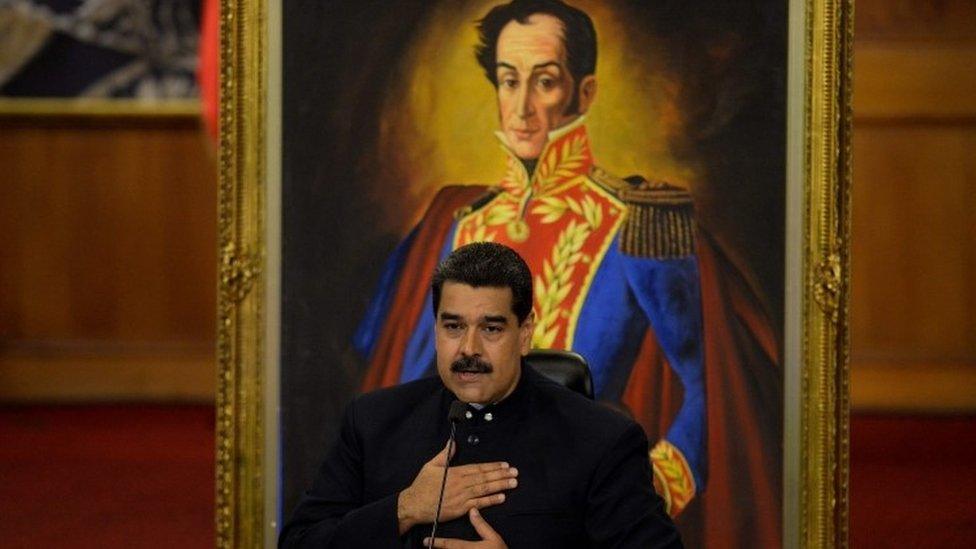

He believes people need to pressure the administration of President Nicolás Maduro more.

"There is a need to retake the streets, non-violently, pacifically," he says. "Right now, I am totally convinced. When you have hundreds of thousands of people protesting, that's what really annoys Maduro."

- Published3 December 2017

- Published18 November 2017

- Published9 November 2017

- Published8 November 2017

- Published15 November 2017

- Published5 November 2017

- Published3 November 2017