Venezuela's polling day: 'Wake up and sort it out'

- Published

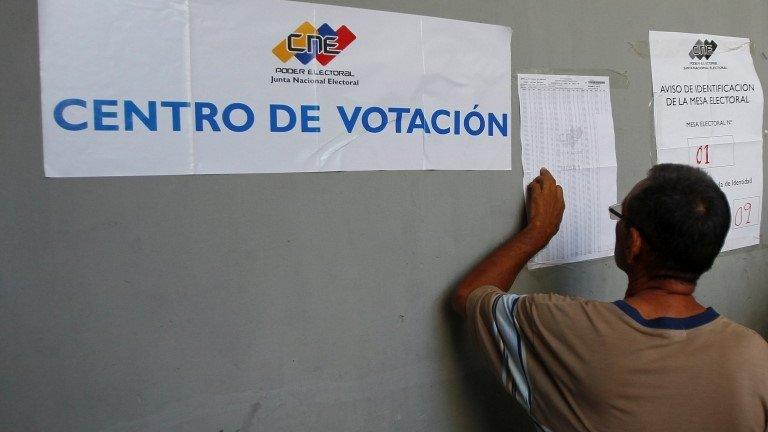

Venezuelans look for their names on electoral rolls before Sunday's mayoral polls

On Sunday, Venezuelans turned out to vote in mayoral elections, the result of which was easy to predict, as opposition parties had boycotted the vote in protest at the government. The BBC's Latin America correspondent Katy Watson reports from Barquisimeto.

At a voting centre in a poor neighbourhood in the municipality of Iribarren, government candidate Luis Jonas Reyes has come to cast his vote. People line up to meet him and give him a hug.

One woman slips a note into his pocket with a wish-list of things she needs from the government. She tells him she's not had any help from them in 18 years. He promises her that will change.

Now more than ever though, the government is struggling to deliver on its promises. That, says Mr Reyes, is not Venezuela's fault.

"We are rising to the challenge of the demands imposed on us by international governments as well as the opposition," he says. "They are imposing sanctions to damage and bloc our economy."

It's a well-used argument that's wearing a little thin among many Venezuelans.

As the queue for the voting centre dies down, another one is forming on the opposite side of the road: people are lining up to register their Carnet de la Patria, a form of identity card that the government says helps them manage welfare benefits more efficiently.

People waiting in line for cooking gas

They're outside the voting centre to try and get as many people signed up as possible. Those in the queue are eager to register for the promised benefits, although not everyone waiting in line is sure what they'll get.

Critics of the government think the card is just another way for the government to control the population. They're sceptical about the registration points placed outside the polling station, believing they could coerce people to vote for the government.

The day before the elections we came across far bigger queues than those at the voting centre. Hundreds of people waiting in line for a delivery of cooking gas.

Queuing from six in the morning, they had to wait eight hours in the heat, hoping for a delivery. They were fed up. They hadn't had cooking gas for two months.

At one point, people blocked the road with tyres in protest.

"We don't have gas, is that fair in an oil rich country?" says Alberto Jose Quintero. "We are the richest country in Latin America, we are suffering from gas, oil, diesel and food shortages - and these problems aren't going anywhere."

Another woman starts shouting.

"The politicians need to wake up and sort it out," she tells the crowd. "I might get in trouble for saying that but I'm Venezuelan and I have needs as does everyone here."

The crowd gives her a round of applause.

Down the road I meet Jose Bolivar. He's a nurse in a public hospital during the week but he can't make ends meet. He earns more with his weekend job as a barber.

Jose Bolivar cuts a customer's hair

Pinned up on the mirror of his simple barbershop is a piece of paper saying haircuts cost 10,000 bolivares (10 US cents on the widely used unofficial exchange rate). Until last week they were half the price but the cost of his hair products has meant he has had to put up prices.

He didn't vote on Sunday because he's angry with the government and he thinks the opposition is a farce. He does say he'll vote if they hold presidential elections. But not for the government.

"I'll vote for anyone who runs - even my neighbour!"

Builder Bernardo in the barber's chair agrees with Jose.

"It's chaos - we're manipulated and treated like puppets."

In the local market nearby, a Venezuelan hit plays out at one of the stalls. It's a love song about a man admitting his faults, claiming he's not perfect. Humility that people would be keen to see from the country's politicians.

- Published11 December 2017

- Published30 October 2017

- Published9 September 2024