The caravan of mothers looking for their lost children

- Published

Every year for the past 13 years, a group of women have travelled 4,000km (2,485 miles) across Mexico searching for their children who went missing while migrating through the country from Central America. Photojournalist Encarni Pindado has spoken to some of the women about their plight and what they aim to achieve with their Caravan of Mothers of Missing Migrants.

The caravan brings together mothers from El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua.

They cross the border between Guatemala and Mexico on inflatable rafts to symbolise the risks the migrants face when crossing into Mexico.

They then travel together across Mexico in search of their relatives who disappeared.

In the 13 years since the caravan was first organised by the Mesoamerican Migrant Movement, 270 missing migrants have been located.

Part of the idea behind the caravan is also to denounce and highlight the issue of disappearances of migrants in transit through Mexico.

Of the 270 missing migrants who have been found, 90% are men. Women are much harder to find, especially when they have been forced into the sex trade. In order to boost their chances of finding those women, the movement has forged links with organisations run by sex workers.

They place pictures of the missing migrants in brothels in the hope someone will recognise their loved ones.

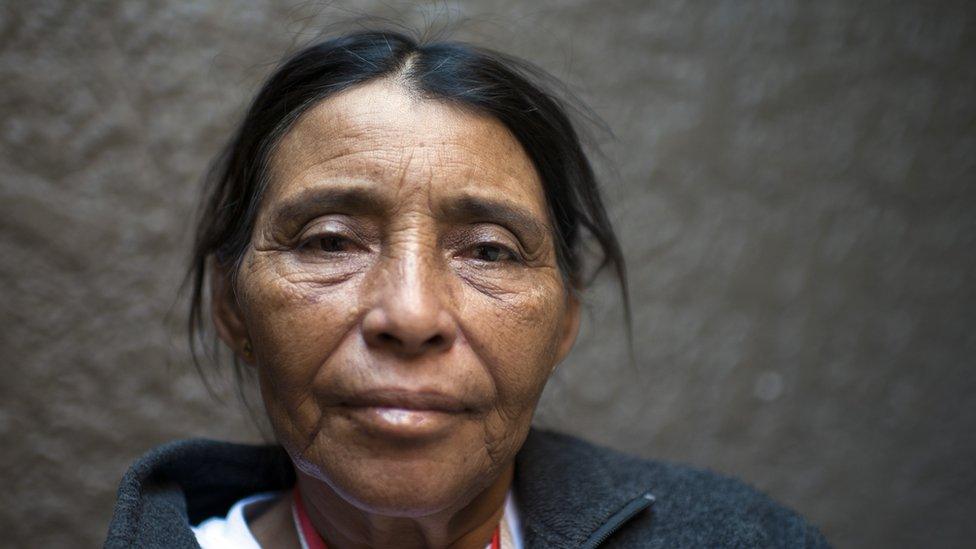

Clementina Murcia González has been part of the mothers' caravan for the last five years. Two of her sons went missing: Jorge in 1984 and Mauricio in 2001.

With the help of a a local radio station, Radio Progresso, she recently managed to track down Mauricio and will be reunited with him in the Mexican city of Guadalajara as part of this year's caravan.

"Sixteen kisses and 16 hugs is all I want from my son," she says about the impending reunion.

Her search for Jorge continues.

Edit Gutierrez's son left Honduras twice.

The first time he was kidnapped by Mexico's infamous drugs cartel, the Zetas, and witnessed how they killed and burned some of the other migrants he had travelled with.

The army eventually rescued him and deported him back to Honduras.

In August 2012, he left Honduras for the second time, paying a people smuggler $3,000 (£2,250) to reach Reynosa, in the north of Mexico.

There he lost all communication with his family.

Isidora de Jesus Zuniga Colindres from Honduras is searching for her son Josue Ildefonso Molinas Zuniga.

Josue last called from the US-Mexican border town of Nuevo Laredo on 15 December, 2013.

He was headed to New York to join his father, who had received temporary protected status in the US years earlier, while his mother stayed behind in Honduras.

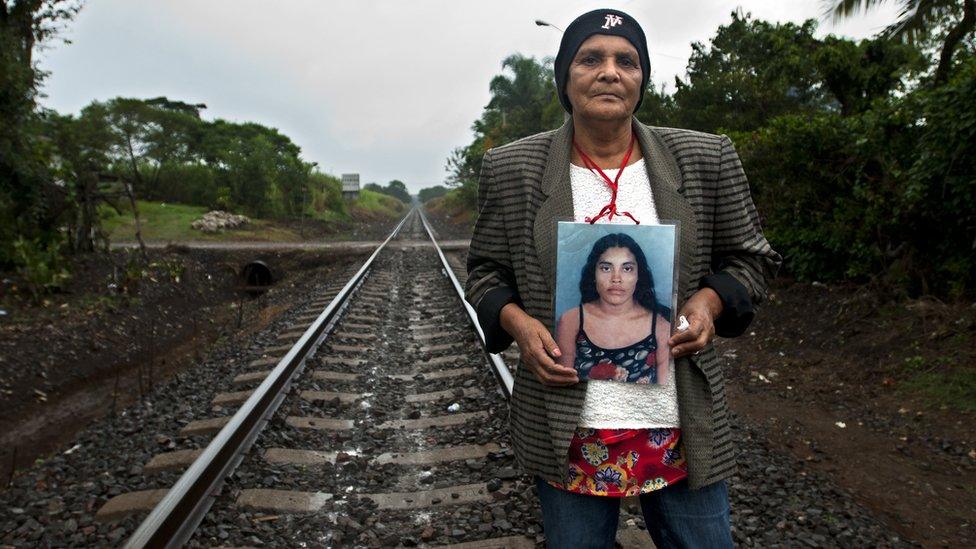

María Clementina Vásquez Hernández is from Honduras. She is looking for her daughter María Ines who emigrated in 2002, leaving behind her infant son.

María Clementina has been raising her grandson in María Ines's absence.

"I'm not even sure what her face looks like now," she says about her daughter.

María Elena Larios has been looking for her son Heriberto, who disappeared on 6 March, 2010.

He left La Libertad in El Salvador, to find work in the United States, but as far as María Elena knows, he never made it.

In the southern Mexican town of Huixtla people tell her to look for her son at a Christian CD stand along the train tracks.

But when she arrives, she finds a slender young man from Honduras who resembles the photograph she carries of her Heriberto but who is not her son.

Pilar Escobar Medina from Honduras is searching for her daughter Olga, with whom she has had only very intermittent contact.

One day in September 2009, Olga did not return to her home in Honduras.

Fifteen days later she called her mother from the city of Tapachula on the Guatemala-Mexico border, saying she had "ended up there".

Ms Escobar did not hear from her again until earlier this year, when they planned a reunion. But in the months before they were due to meet, Olga's phone line went dead.

"Before migrants died of thirst, or were bitten by a snake while crossing the desert. Today they die at the hands of organised crime, and our girls, are raped by [people linked to] organised crime" says Rosa Nelly Santos, who heads a committee for disappeared migrants in Honduras.

Mercedes Lemus (left) is searching for her daughter Ana Victoria, who went disappeared on 16 April, 2010.

Last year, a woman in Huixtla told her that she had seen her daughter in a local bar.

Neighbours confirmed that the picture of Ana Victoria resembled a woman they had seen around town with the bar's owner.

But when Mercedes asked for permission to enter the bar, the bouncer warned her that if she went in, she would not come out alive.

Along the way, the caravan meets local communities. In La Ceiba, a cultural and educational centre working with indigenous communities in Chiapas, the mothers are invited to a Mayan ceremony, a pre-hispanic ritual to connect with ancestors.

All photographs by Encarni Pindado.