Why Guyana's rainforests are a scientist's dream

- Published

Andrew Snyder came across an electric blue tarantula in the rainforest of Guyana

When herpetologist Andrew Snyder's flashlight landed on something bright blue in the rainforests of Guyana, South America, he stopped and took a closer look.

It turned out to be a blue tarantula of the Ischnocolinae subfamily, a species most likely unknown to science.

"It was very exciting to say the least," says the PhD candidate from the University of Mississippi.

"I had no idea that it would turn out to be such a stunning tarantula but I'm glad that I went with my instincts to double check."

Mr Snyder made the discovery during a biodiversity assessment team survey led by World Wildlife Fund (WWF) Guianas and Global Wildlife Conservation.

In total, the researchers found more than 30 species that are likely to be new to science.

Guyana is home to many unusual species such as Stefania evansi, also known as the Groete Creek Carrying Frog, which rears its offspring on its back until they are ready to fend for themselves

These include six species of fish, three plants, 15 aquatic beetles and five odonates, better known as dragonflies and damselflies.

The Kaieteur Plateau-Upper Potaro region, where the survey took place in 2014, is a rich habitat for spectacular and endangered species such as the Tepui swift, the jaguar, the Guianan cock-of-the-rock, the white-lipped peccary and the golden rocket frog.

It is also home to many species that are endemic to the Guiana Shield and Guyana specifically.

Sharing expertise

The team behind the research comprised scientists, field support assistants and experts from Brazil, Canada, the US and, of course, Guyana.

The survey was all about team work. Here they discuss where to set up camera traps.

In this survey, for example, the lead of the water-quality team and one of the senior members of the fish team were Guyanese while the community field assistants included residents of Chenapau, an indigenous village located near to the research site, as well undergraduate students from the University of Guyana.

One of those students was Nelanie La Cruz, who recently returned to Guyana after completing a Master's degree in aquatic science at University College London.

"They asked if I wanted to assist the scientist studying water beetles and I was really excited by that," she said.

"I and another student worked with him for about three days or so, then he left us to continue doing the collection. It was very cool, a definite boost to the confidence."

"We're investing in bringing in new blood and expertise to organisations like ours," explains Aiesha Williams, WWF Guianas country manager for Guyana.

"Working in partnership with other scientists from different parts of the world can help build the capacity that we have here and ensure a kind of exchange."

Experts in their field

Without expertise and logistical support from local residents, navigating the remote Kaieteur National Park, the oldest protected area in the Amazon, and the Upper Potaro region would have been near impossible.

"People on the ground know a lot more than you going in [to the field]," says Ms Williams. "They know a lot about the area, the biodiversity, its uses… it is part of their lives and livelihoods."

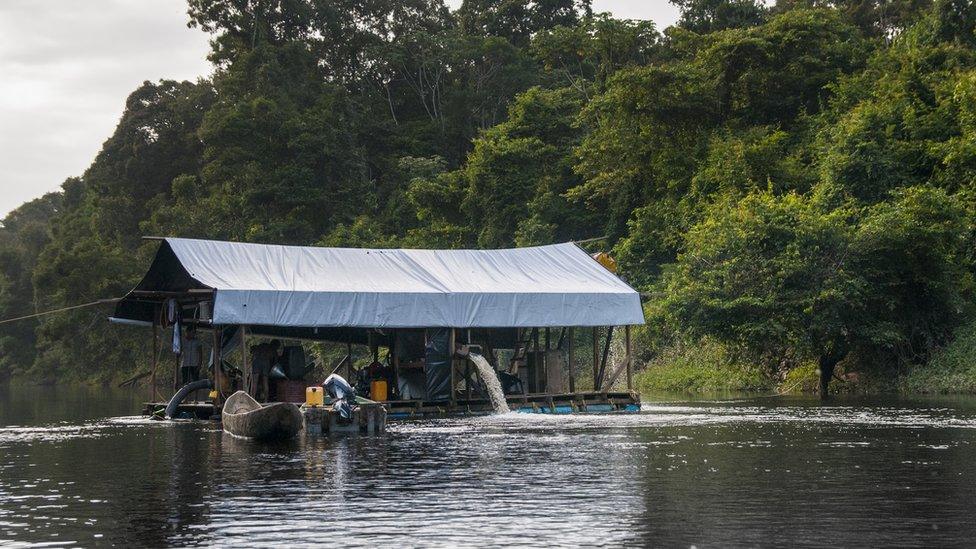

Through these local partnerships, WWF Guianas also plans to address environmental concerns such as the impact of gold and diamond mining on the water and biodiversity of the region, often a heated topic given the reliance of many residents on natural resource extraction.

The researchers are worried about the impact mining could have on aquatic ecosystems

It is hoped that the documentation of the biological diversity will allow Kaieteur National Park wardens, officials from Guyana's Protected Areas Commission and residents themselves to make more informed decisions about land use and management of natural resources.

Due recognition

Although WWF Guianas says it recognises the important role of indigenous people, equal status is not always given to non-academic scientists by environmental and conservation groups both inside and outside of Guyana.

The spectacular Kaieteur Falls, where the Potaro River cascades down 741 feet, is located within Kaieteur National Park

"Academics have used our knowledge of our lands and living things in them to promote themselves and the general science," says Laura George, governance and rights coordinator of the Amerindian People's Association in Guyana.

"It is time that they acknowledge indigenous peoples as the first and true scientists."

One way to involve indigenous science, suggests Ms George, is to give space in official reports for local names, such as Camaliya, the word for Tepui swift in the Patamona language of Chenapau.

Another, she says, is providing more opportunities in higher education.

"While the report makes mention of residents who contributed to the expedition, there is no substantial sustainability to support indigenous peoples in being recognised or towards becoming 'academic scientists'."

"These researches must support outcomes that support and respect indigenous peoples as the true and first knowledge holders and the true protectors of the lands."

- Published19 December 2017

- Published31 August 2017

- Published18 May 2017

- Published19 March 2017

- Published29 January 2017

- Published6 November 2016