Colombia prisoners regain self-esteem through theatre

- Published

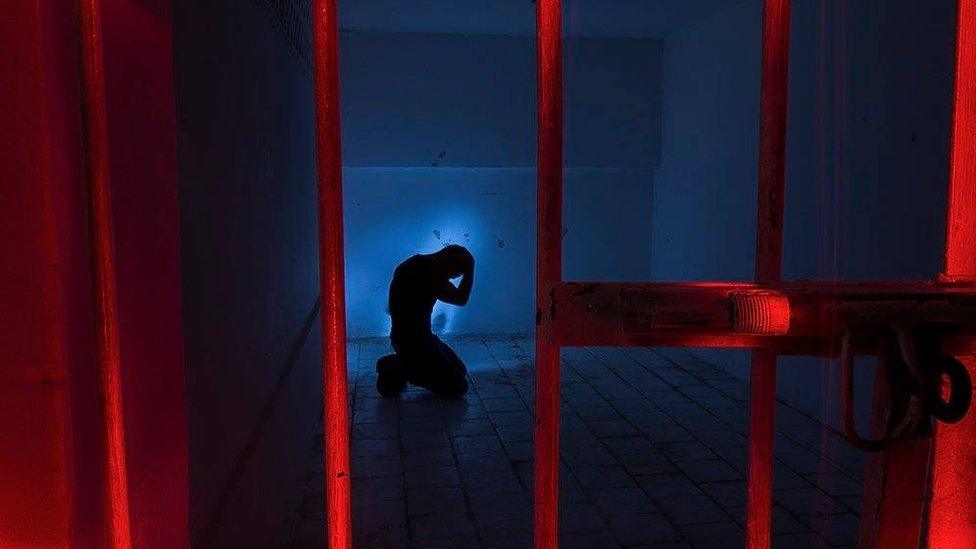

Theatre became a way to escape the drudgery of the prison routine for Mario Salazar

Mario Salazar never imagined he would one day be grateful for the time he spent in prison.

The Colombian investor was arrested in Bogotá as he was about to board a plane to the city of Cali in 2012.

He was convinced the authorities had made a mistake but, as it turned out, it was he who had made the mistake.

Eleven years earlier, he had been summoned to court on fraud charges. He attended the first hearing convinced the case would soon be dismissed.

So nonchalant was he, that when he moved home, it never occurred to him to register his change of address with the authorities. Subsequent court summons did not reach him.

Since he never again showed up at court, the Colombian justice system sentenced him in absentia to six years in prison, and issued his arrest warrant.

Six-year sentence

It was only when he was taken to La Picota, one of Colombia's most infamous prisons, that he remembered the fraud case which had landed him there.

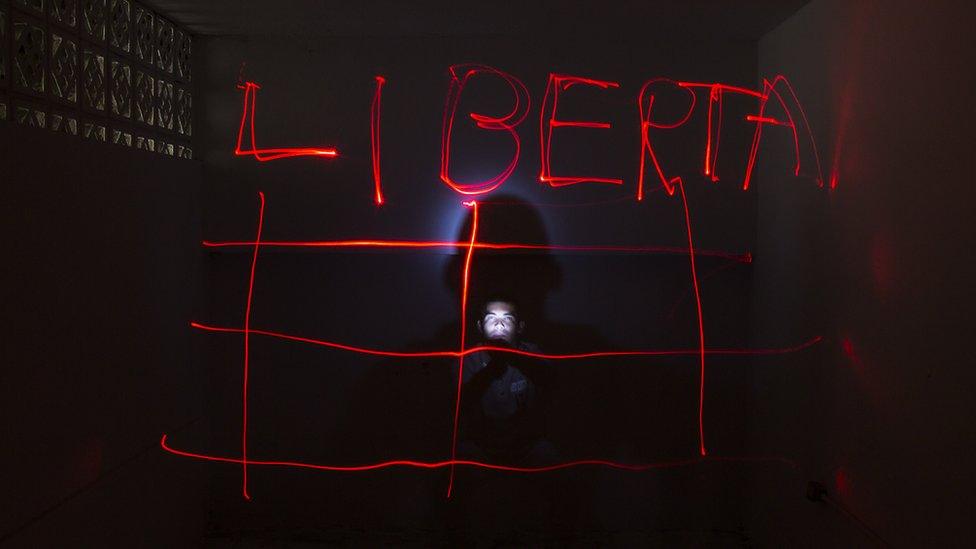

Mario Salazar was dreaming of "libertad" (freedom), something he would achieve earlier through the workshops he taught

Keen to escape the confines of his prison cell from day one, he asked to be allowed to go to the prison library.

Read more stories like this:

There he saw a piano which gave him an idea. He knew how to play piano and maybe giving lessons to other inmates could help reduce his sentence?

He approached the prison authorities and while they did not agree to his plan for piano lessons, they proposed an alternative.

They needed someone to lead a project backed by the justice ministry to create theatre groups in prison.

Salazar agreed to found a troupe in La Picota.

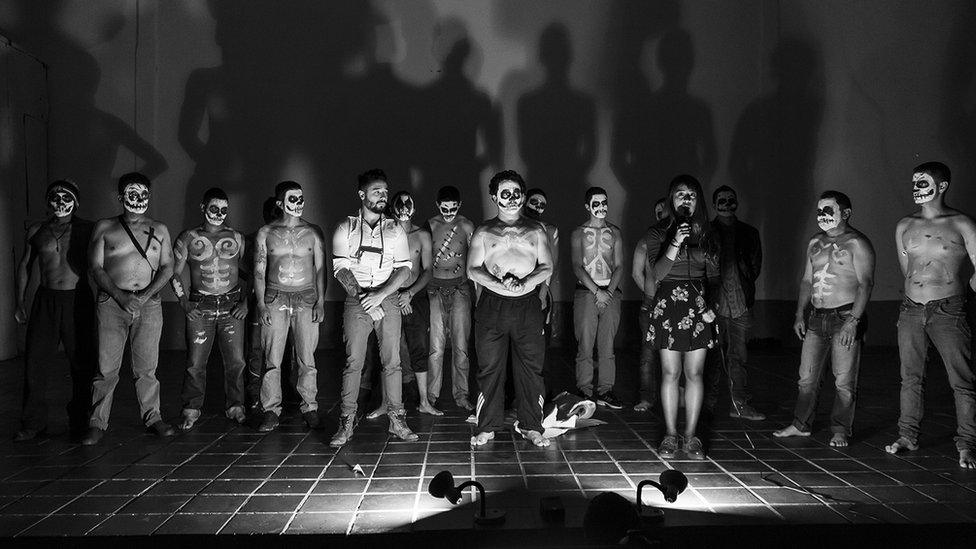

At first, 10 inmates joined La Picota's theatre group

He held an audition amongst the prisoners and chose 10 out of the 50 who presented themselves.

They began to study screenplays and staged Roberto Zucco, a French comedy based on the real-life story of a young man who murdered his father, was locked up and escaped.

Life-changing

For Salazar, the theatre group became a respite from the depression caused by prison life. He made new friends and it made him reflect on his life, he says.

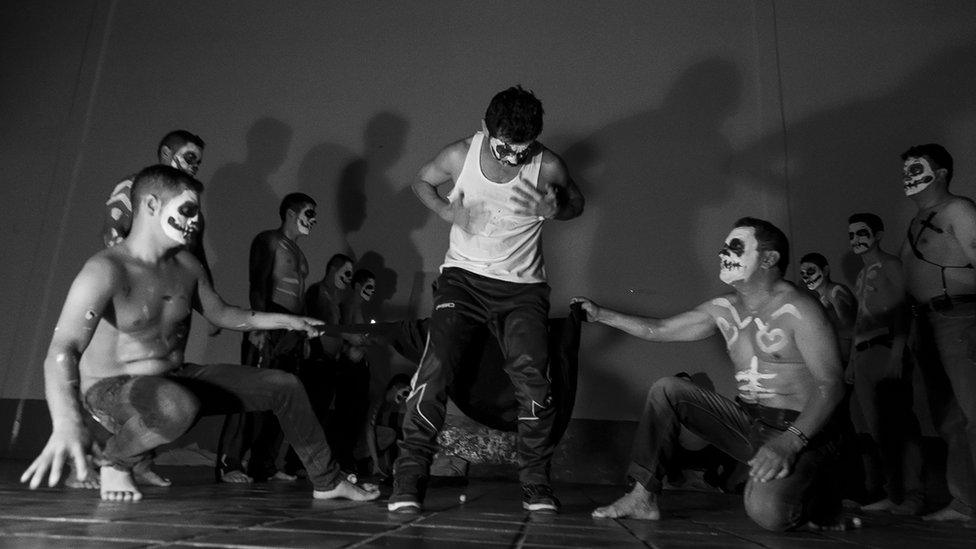

Inmates have performed both inside and outside of the prison

He began to see his prison term as something positive, as something that grounded him.

He says he wished he had been a better father to his 11-year-old daughter and a better husband to his ex-wife.

"Life billed me for my errors with prison," he concludes, now 44 with greying hair but a still youthful face.

Salazar's dedication to the theatre project was recognised by the authorities with a reduction in his sentence from six years to three.

But with his life thoroughly changed, returning to his job as an investor was not an option for Salazar.

'Not like university'

During his time in La Picota he had also met a woman who shared his passion for prison education.

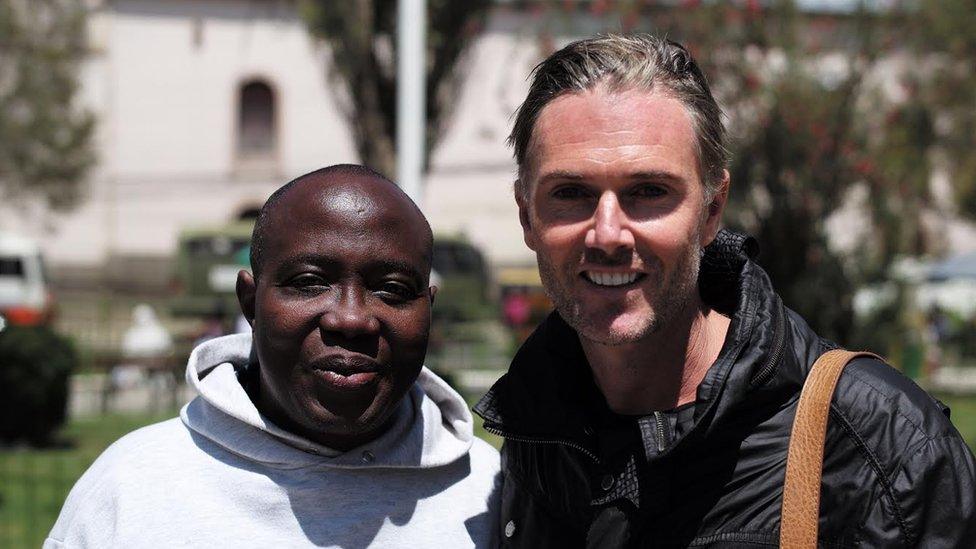

Mario Salazar teamed up with student Tatiana Arango to teach inmates workshops

Student Tatiana Arango taught a literature appreciation course in La Picota which the prison warden encouraged Salazar's theatre group to attend.

Salazar says there was immediate chemistry between the two but it took them almost a year to acknowledge their feelings for each other.

For her master's thesis, Ms Arango developed an educational model focussing on art and after Salazar's release the two set up a foundation to put her model into practice.

The Salazar Arango foundation now holds a wide variety of workshops in La Picota.

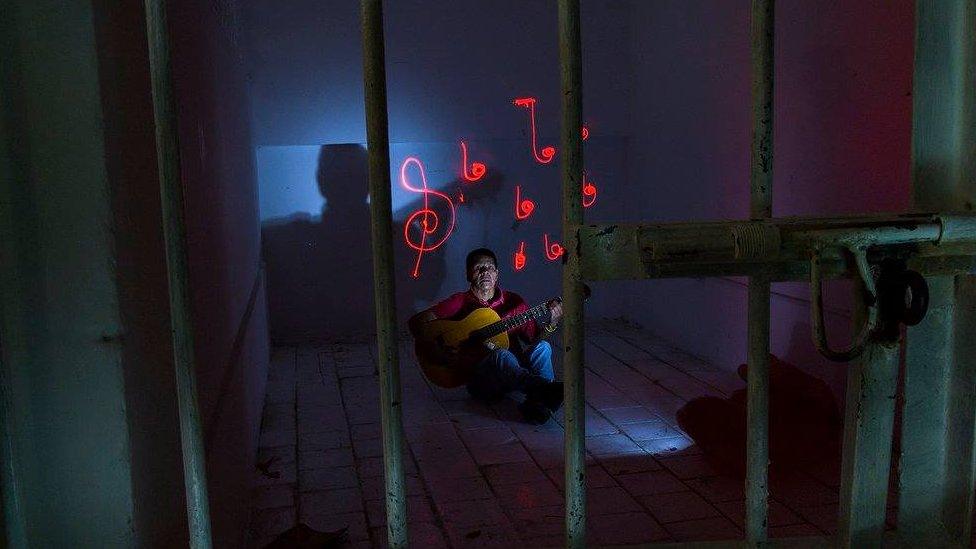

Colombian artist Antonio Galante runs light painting workshops with prisoners in La Picota

About 100 prisoners attend their twice-weekly theatre, music, literature, drawing, circus and radio workshops. Among those who take part are thieves, rapists, murderers, rebels and paramilitaries.

"This is not like teaching at university," Ms Arango says. She says that the instructors have to adapt the curriculum to tackle some of the extremely negative emotions inmates have.

She says that staff have found that theatre in particular does wonders for prisoners' self-esteem. Inmate David Gonzáles is a shining example of what the programme can achieve.

Gonzales was jailed for electronic theft after he and his gang of hackers stole from banks.

'Factory of monsters'

He first got involved with the Salazar Arango foundation through a photography workshop six months after he was jailed. But it was the theatre workshop where he really shone. He wrote his own play about the emotional stages many prisoners live through, ranging from depression to fear.

And with his newly found confidence he convinced the prison authorities to let him dust off the piano and a few guitars stored in the prison library to create La Picota's only rock band.

Abolition is a rock band made up of inmates of La Picota

With a drum set made of tambourines, congas and buckets, the band, called Abolition, performs inside La Picota several times a year.

In October, the foundation even managed to get permission for Abolition to perform in Bogotá's central Bolívar square.

Gonzáles says he burst with pride when he heard his fellow inmates sing his songs in front of thousands of people.

Prison, he says, has a dangerous dehumanising effect. "I see this system as a factory of monsters who sooner or later will be thrown into society," he says about the prison regime at La Picota.

But through the work of the foundation, he adds, inmates have regained some self-respect.

"They make it clear that, no matter how terrible our crimes, we are also worthy of standing on the theatre stage."

All photographs courtesy of the Salazar Arango Foundation.

- Published20 October 2017

- Published9 April 2017

- Published25 February 2017

- Published18 July 2015