Why Pope Francis's trip to Chile poses a challenge

- Published

Pope Francis is likely to face hostility on his official visit to Chile

When the Vatican Secretary of State Cardinal Pietro Parolin said that Pope Francis's trip to Chile would not be an easy one, it was no exaggeration.

In the pontiff's 22nd overseas visit, he will meet an unprecedented degree of hostility on his native continent.

When asked to evaluate Pope Francis on a scale of 0 to 10, Chileans gave him a score of 5.3, the lowest ranking for any Pope.

Trust in the Catholic Church as an institution fared even worse, polling at just 36% - the lowest in Latin America.

With such a low rating, it is not surprising that before boarding his plane from Rome, Pope Francis asked his congregation to pray for him.

Chile is a land of contrasts. It is estimated that more than 60% of the population identifies itself as Christian, and 45% belongs to the Catholic Church. But it is also the second most secular country in Latin America.

Some 38% of Chileans regard themselves as agnostic, atheist or non-religious.

So what are the three main challenges the Pope will face on his Chilean trip?

1: Corruption and poverty

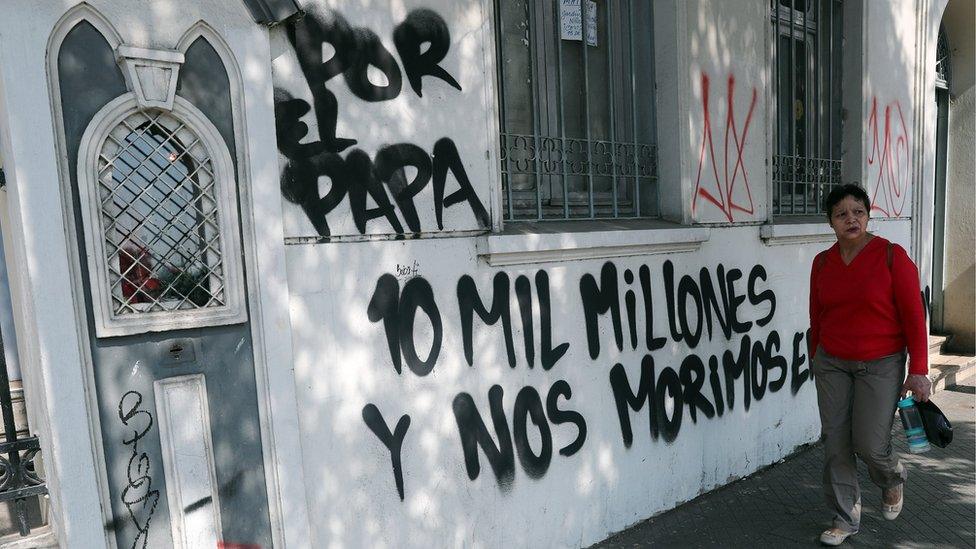

In the days before Pope Francis was due to land in Chile, the visit came under criticism for the costs involved while so many people were struggling under the poverty threshold.

Catholic churches in the capital, Santiago, were firebombed, causing minor damage but sending a clear message.

Three churches caught fire after they were targeted with homemade devices. A fourth church was spared any damage after an explosive was defused, but a message left on a wall nearby read: "The poor are dying."

Flyers were also left at the properties, warning that the next target would be the Pope.

Police take pictures at the Santa Isabel de Hungria Church in Santiago, which came under attack

The Apostolic Nunciature was also occupied briefly with protesters complaining about the expense of the pontiff's trip.

The lack of initiative in fighting against corruption is also seen by many Chileans as a way of slowing down development and keeping poor people from prospering.

2: Resentment after sexual abuse scandal cover-up

The Catholic Church in Chile has yet to recover from the downward spiral that began with the so-called Karadima abuse case.

For more than a decade, local church leaders ignored complaints against the highly influential Fernando Karadima, a Roman Catholic priest accused of molesting children.

When the victims went public, the Vatican finally investigated the affair and Fr Karadima was found guilty in 2011.

Protesters tried to stop the ordination of Juan Barros as bishop

Pope Francis has made clear his "zero tolerance" for abuse, but his appointment of one of Fr Karadima's protégés - Juan Barros - as the bishop of Osorno in southern Chile has reopened old wounds.

According to Fr Karadima's victims, Bishop Barros was aware of the abuse but allowed it to happen, although he denies knowing of the crimes.

In an open letter, James Hamilton, one of Fr Karadima's best-known and outspoken victims, said: "I still don't understand how we, the thousands of victims of abuse, were not protected by our priests, who were silent witnesses to what was happening to us."

3: Indigenous discontent

On Wednesday, Pope Francis will visit Temuco, a city in southern Chile that acts as the de facto capital for the indigenous Mapuche people.

The Mapuche community has opposed colonisation for 300 years - fighting against Spanish colonisers first, then the Chilean nation-state - in what is considered one of Latin America's longest-running conflicts. It is a conflict that erupts in violence periodically.

The Pope will visit Temuco, the de facto capital for the Mapuche community

The Pope is to celebrate a mass for "the progress of peoples" followed by lunch with Mapuche representatives.

There are longstanding issues for this community - among them, ancestral land ownership, and legal recognition for the Mapuche language and culture.

Leaders hope that Pope Francis can help them end decades of discrimination, and bridge differences.

- Published12 January 2018

- Published15 January 2018

- Published11 December 2023