The island where 19th Century land ownership is at risk

- Published

Changes to the Barbuda Land Act dominate every conversation, even this game of dominoes

Around the dominoes table, spirits appear high but faces are weary. It is not long before the light-hearted banter is replaced by the topic currently dominating every conversation in Barbuda.

Islanders say that government plans to overturn a centuries-old system of communal land ownership will destroy their unique way of life and erase their cultural identity.

The controversial bill introducing the freehold sale of land would revoke this 19th Century practice, which was enshrined into law in 2007.

It is now gathering pace after being passed by both chambers of Antigua and Barbuda's parliament.

Communal ownership

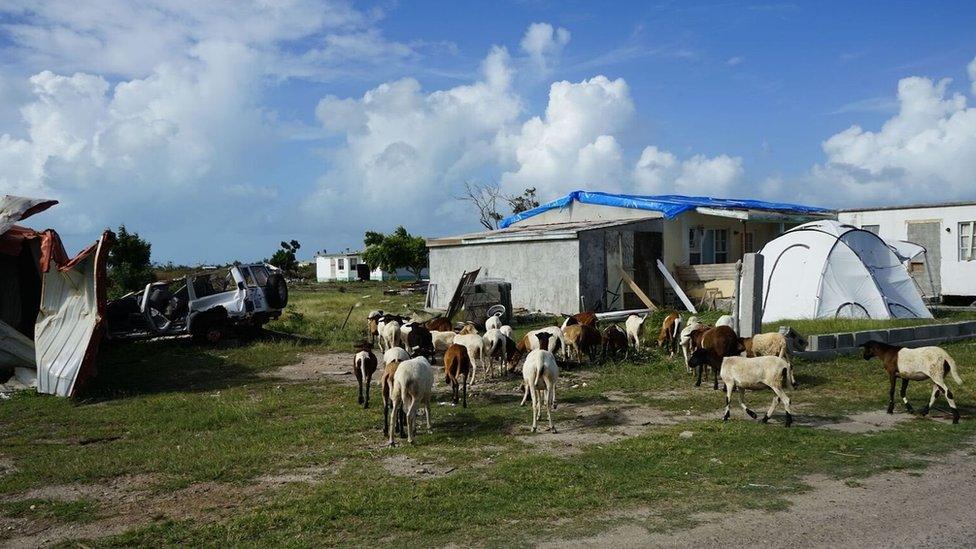

Here, in this makeshift bar amid the ruins of Barbuda's once charming capital, people are still reeling from the wrath of devastating Hurricane Irma.

Almost five months after the monster storm ripped the tiny Caribbean island apart, destroying homes and vital infrastructure, depression is setting in.

Electricity and running water have yet to be restored to individual homes, though running water is available intermittently via standpipes.

Schools remain closed and less than 400 of Barbuda's 1,800-strong population have returned home following September's mandatory evacuation to the sister isle of Antigua.

Prime Minister Gaston Browne says allowing parcels of land to be sold will raise the revenue Barbuda needs to rebuild.

Under the existing system, Barbudans govern all land communally with no private ownership.

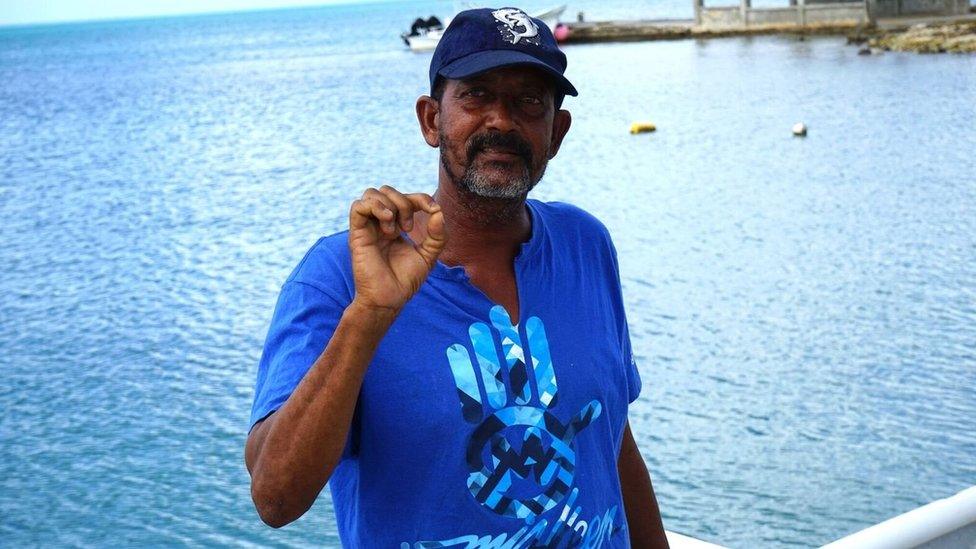

Barbudan fisherman Devon Warner says that "the government is kicking us while we're down"

Residents can identify parcels for residential, commercial or agricultural use which are then approved by the Barbuda Council and can be passed on to their heirs.

Many fear the changes will open the floodgates to wealthy foreign investors and transform the quaint, pristine isle into a tourism hotspot.

'No consent without consultation'

Earlier this month, an application for an injunction to put the brakes on the process was refused by the High Court.

The lawyer representing those behind the application, British QC Leslie Thomas, argues that the government has contravened laws which state that communal ownership can be repealed only with the consent of the majority of the Barbudan people.

Farming and fishing have been Barbuda's economic mainstay for centuries

Public meetings have traditionally been held to gauge consensus on various issues.

"You can't seek consent without consultation," Mr Thomas tells the BBC, adding that campaigners were prepared to fight all the way to London's Privy Council, the country's final court of appeal.

An early version of the bill sought to limit freehold titles to 10,000 sq ft (0.23 acre) per person with sale prices to be determined by government.

That caused fears among some residents as to what the government would do with the remaining land, which under the draft version it would have been free to dispose of as it saw fit.

Concerns also abound that introducing the sale of land will price future generations out of the market.

"As soon as the land is sold, it is lost to us," secondary school principal John Mussington said.

John Mussington (pictured here with his daughter) is one of six protesters who want to fight the plans through the courts

"Our traditional lifestyles of farming and hunting, which require large amounts of land and have been our economy for hundreds of years, will be completely disenfranchised. Our resources will be removed with one stroke of a pen."

The government said it was still "ironing out the mechanics" and the final version signed by the governor-general on 22 January no longer contains any reference to the 10,000 sq ft limit.

Upsides

Residents have welcomed some of the proposed changes.

Loosening the rules to allow those with one Barbudan parent, rather than two, to become landowners is fair, says local resident Goldie Harris.

But he, like many others, is angry about the lack of public consultation.

Resident Thomas Thomas fears the bill could be the end of Barbuda's close-knit community

"We were never notified, we never received a copy of the changes to the land act; they just rammed it down our throats," he alleges.

"This island is paradise for us but the government sees it as a money-maker for high rollers. I agree Barbuda needs development, but on a limited basis. Our children will never be able to afford land here," he adds.

Thomas Thomas, another resident, fears the close-knit community, where neighbours are considered family and doors are left unlocked, will change.

'Empowering move'

Arthur Nibbs is a strong supporter of the bill. Mr Nibbs, who is the minister for agriculture, lands, fisheries and Barbuda affairs, says islanders have been consulted, but "in batches, not in the regular form".

He says Crown land would only be available to Barbudans and foreign investors would continue to apply for leases.

"Barbudans have long been tenants of the Crown, with a right to occupy. This will empower them to become land owners," he adds.

Barbudans say the bill comes at a time when they are still recovering from Hurricane Irma

An earlier draft of the bill, which has since been revised, sought to replace the word "Barbudan" with "resident of Barbuda" in some places in the text.

This sparked fears the bill would pave the way for foreigners to acquire freehold titles, which are currently restricted to Barbudans.

"I want my grandkids to have the same privileges we had, to acquire land freely and do what they want to do," says farmer Shiraz Hopkins.

"If my son wants another piece of land it will be priced way too high for him," he says about the plans.

Island-wide, frustration is omnipresent. Not just at the looming changes to the way of life, but the minutiae of them too.

Many are angry that work to build a new airport runway is continuing while most Barbudans still have no home to return to

There is the daily trudge for water to bathe, cook and clean and the cost of running generators.

"We are tired and fed up," Kelly Burton says. "And on top of everything, this bill seeks to erase our heritage."

On the boat back to Antigua, a calypso song blasts out a nostalgic homage to yesteryear. With Barbuda's future uncertain, it is a poignant tribute to an island which, in a few years' time, might look very different.

Correction 14 February 2018: This article referred to the wording from an earlier draft of the bill and has been amended to clarify the contents of the final version.

- Published12 October 2017

- Published8 September 2017