A little corner of Brazil that is forever Okinawa

- Published

In the Sao Paulo neighbourhood of Liberdade, samba and Japanese tradition often mix

Who would have known that the Okinawan language found a home in Brazil just when it was fading back in Japan? BBC Brasil's Leticia Mori has this report from Sao Paulo.

Walking around Liberdade district, you would be forgiven for thinking you were in Tokyo. Nowhere in Brazil are the influences of Japanese immigration more visible than in this bustling part of Brazil's biggest metropolis.

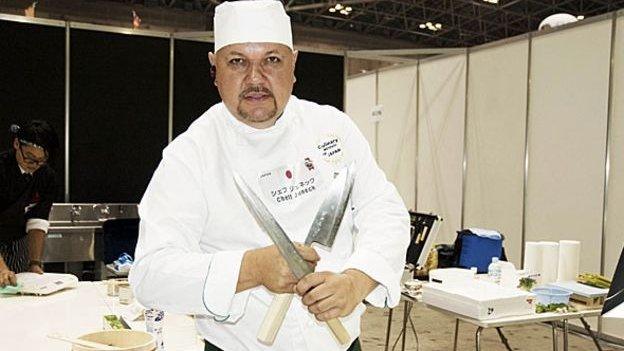

Japanese food is popular in Brazil

Typical Japanese archways span streets in Sao Paulo

The names on shop fronts are in Japanese and they sell everything from Japanese food and kitchen utensils to traditional home decorations.

Red painted archways and a Japanese garden delight visitors venturing to this little Japanese corner of Brazil.

Japanese migration to Brazil is celebrated annually on the anniversary of 18 June 1908, the date when the Japanese ship Kasato-Maru arrived in the port of Santos, south of Sao Paulo, carrying the first 781 people to take advantage of a bilateral agreement promoting migration.

Half of them were from the southern part of the island of Okinawa, located about 640km (400 miles) south of the rest of Japan, which had its own distinct language and culture dating back to before the island's annexation by Tokyo in 1879.

Today, Brazil is home to the world's largest community of Japanese descendants outside of Japan, numbering about 1.5 million people.

Why did they come from Okinawa?

Japanese authorities promoted emigration as a national policy until the late 1960s to alleviate poverty and overpopulation and encouraged people from rural areas in particular to seek work abroad.

Brazil has a large community of people descended from Japanese immigrants

There had been earlier policies to send migrants to work as labourers in the Hawaiian sugarcane fields, on the US mainland and Canada's West Coast and, to some extent, in Mexico but they proved short-lived as those countries adopted restrictions on immigration.

Tokyo soon started looking for opportunities further south.

Brazil, where slavery had been abolished in 1888, was looking for cheap labour to work in the coffee plantations of its south-east.

Japanese migrants filled that gap but quickly many realised they could earn more by working their own land.

The community soon prospered working the rich, arable lands of Sao Paulo state, where they revolutionised agricultural techniques, growing a variety of vegetables, rice and greens, some of which they introduced to the country.

Unlike in their homeland, where the Japanese authorities banned the Okinawan language following the islands annexation, Okinawans living in Brazil were free to speak their language and celebrate their culture.

What happened to their language?

Yoko Gushiken, 70, came to Brazil when she was 10.

Yoko Gushiken (top row, far right) continued to practice traditional dances after she emigrated

"If we spoke Okinawan at school, we'd be punished but at home I spoke it secretly," she says about her childhood back home.

She says that she and her older brother, both of whom settled in Brazil, still speak Okinawan fluently.

But back in Japan, its speakers are few and far between, prompting Unesco to add it to its list of endangered languages.

Ms Gushiken says her sister, who stayed in Japan, struggles to understand it.

"Once I went to visit her and we went to the theatre," she recalls. "The play was in Okinawan. I understood everything, and she didn't."

Roots music or pop?

The fact that Okinawan culture has thrived in Brazil is now attracting university students like Mei Nakamura and Momoka Shimabukuro, who have travelled to Sao Paulo all the way from Okinawa to get in touch with their roots.

Momoka Shimabukuro (left) has come to Brazil to explore her identity while Mei Nakamura is studying psychology

Ms Nakamura studies psychology and says she wants to understand how early migrants organised themselves in their new homeland.

Ms Shimabukuro says she came for personal reasons: "I was born and raised in Kin, a small town in Okinawa. I want to try and see things from a distance to try and find my own identity.

"Perhaps I'll find happiness through this external viewpoint."

Things back in Okinawa have changed, too, since the days of its annexation, with Tokyo now trying to showcase Okinawan culture.

"They are trying to portray a 'pop' Okinawa, with music and animes," historian Ricardo Sorgon Pires explains.

"More people are interested in understanding their [Okinawan] roots and that has translated into more interest in Brazil," the academic from the University of Sao Paulo says.

Who sings in Okinawan?

Another young Okinawan who has come to Brazil to learn about her culture is singer Megumi Gushi.

Megumi Gushi plays the sanshin and sings in Okinawan

Ms Gushi is in Brazil on an exchange programme and her aim is to improve her pronunciation so she can better sing in Okinawan.

During her stay in Sao Paulo, she has spent time with elderly migrants as well as folklore groups which still play the sanshin, a traditional snakeskin-covered string instrument.

Terio Uehara is the president of the Okinawa Association of Vila Carrao, which forms part of the exchange programme.

He argues Okinawan culture is so vibrant here precisely because it has had to survive so far from its homeland.

"In Okinawa, family roots are highly valued," says. "Most descendants know what town their family is from, and even what district. Okinawans are very united and they need to be even more so when they go abroad."

- Published17 July 2015

- Published19 July 2016