Brazil's samba schools go political as funding cuts bite

- Published

Samba schools hope to rise like a phoenix from the ashes of funding cuts

Rio de Janeiro's top 13 samba schools are gearing up for carnival and the parade at Rio's Sambadrome where they will compete on 11 and 12 February to be crowned carnival champions.

Ninety-thousand people will be watching the colourful spectacle from inside the vast Sambadrome, with millions more expected to tune in on TV.

Despite the event's enduring popularity, 2018 is proving a tough year for the leading samba schools after Rio's new mayor, Marcello Crivella, cut their public funding by half.

But the schools refuse to be disheartened. Mangueira, one of the most traditional samba schools, has even turned the funding cut into its main theme.

Its motto for this year's parade is: "With or without money, I will play."

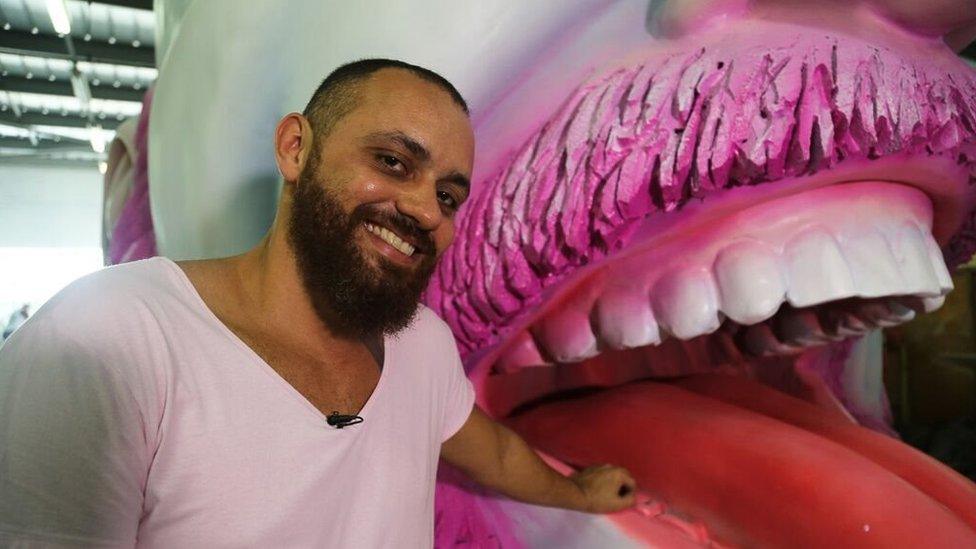

The school is preparing for the big event. Cherubs that will wave jauntily from the floats have been spray-painted gold and workers have also been busy putting the finishing touches to laughing polystyrene figures.

Mangueira's artistic director, Leandro Vieira, says the funding cuts aren't stopping them. "Our parade intends to reaffirm that we are carnival people given to joy, given to freedom," he says.

Beija-Flor samba school says it has been "inspired" by Brazil's dirty politics. Corruption has dominated the country's news, with former president Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva being sentenced to 12 years in prison and top business executives and dozens of politicians under investigation over a huge graft scandal.

Beija-Flor, which has won 13 championships, has chosen to portray the country's troubles by placing a huge rat on one of its floats.

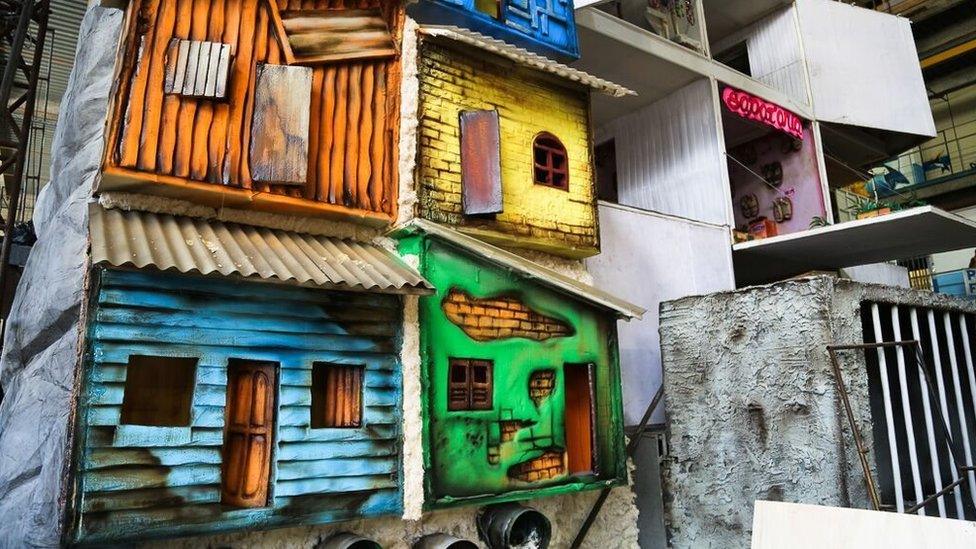

Beija-Flor has also built a colourful polystyrene version of the headquarters of Petrobras, the state-run oil company at the centre of one Brazil's biggest corruption scandals.

But instead of it looking like a gleaming, modern building, it has been made to look like a collection of ramshackle huts.

The school's artistic director, Marcelo Misailidis, says it is meant to show how corruption drives Brazilians into poverty and life in the favelas, the sprawling neighbourhoods where many of Rio's poor live.

Marcelo Misailidis says he wants Brazilians to examine their own conscience.

"We always point the finger at others. We say someone is ambitious and corrupt but who puts the politicians in power?

"Who is creator and who is the creation?" he asks. That, he says, is the question behind the theme the samba school has chosen for this year: a tribute to Mary Shelley's Frankenstein.

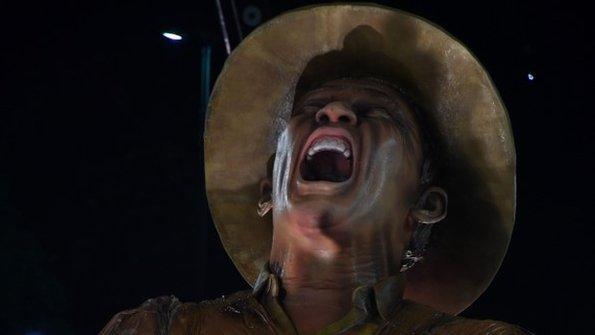

Paraiso do Tuiuti, another school, is also not shying away from thorny subjects. Its theme this year is "My God, My God, is slavery extinct?".

It looks not just at the history of slavery in Brazil, which was the last country in the Western Hemisphere to officially abolish the practice, but also at modern-day slavery.

Golden shackles, feathers and African-inspired headdresses will feature prominently, as the sketches for the school's costumes show.

But their parade will also feature more modern costumes criticising the lack of workers' rights in Brazil, such as suits with four arms to show how some people have to work four jobs to make ends meet.

While the samba schools have drawn inspiration from the funding cuts and Brazil's wider problems, those putting together the costumes worry about their future.

Flavia Jacob, 52, is one of eight members of her family who work at the Paraiso do Tuiuti samba school.

For her and her family, future funding cuts to the samba schools could do more than ruin carnival. If the money continues to dry up, Flavia may not be able to continue adopting Mangueira's motto of "With or without money, I will play".

- Published2 March 2017

- Published28 February 2017

- Published27 February 2017

- Published10 February 2016

- Published5 February 2016