Haitian Oxfam workers tried to warn of sex scandal before

- Published

For an industry that generally operates in the shadows, prostitution in Haiti is barely hidden from view.

On certain street corners of Pétion-Ville, an upscale suburb of the capital, young sex workers huddle in groups, hoping to persuade one of the scores of SUVs driving around the hillsides to pull over.

It is no coincidence that many of the bars popular with expats are nearby.

From Save the Children to the Caris Foundation, some international aid agencies have traditionally tried to help to Haiti's sex workers through sexual health clinics or HIV/AIDS-testing programmes for mothers and infants.

However, it appears that instead of offering unconditional support to these women, in 2011 several members of Oxfam's team in Haiti preyed on them.

Various senior aid workers, including the disgraced country director Roland Van Hauwermeiren, allegedly paid local prostitutes for sex.

That men could be exploiting some of the most vulnerable people in the poorest country in the Americas, all the while being paid to advocate for their wellbeing, is a hypocrisy not lost on Josefine.

The former Oxfam employee, whose name has been changed, worked under Mr Van Hauwemeiren at the time and said there was a culture of abuse, which included sexual harassment, in the Port-au-Prince office.

"Powerful people did whatever they wanted and they got away with it," she tells me in a hotel cafe in the capital, kneading her hands anxiously.

"That's what I would say, there was no protection for victims."

Another Oxfam employee Widza Bryant has also spoken to the BBC

Josefine is still too scared to talk freely. She said she raised her concerns once and it cost her her job. It was enough to put her off from trying again.

"People did try [to speak out], there were some good people who tried. But something bigger should have been done so they didn't go on to get jobs in other places."

She is referring to the fact that Mr Van Hauwermeiren ended up taking another high-profile position, as the head of mission for Action Against Hunger in Bangladesh. What angers her most though, is that it appears allegations of misconduct about the men had been raised before they even arrived in Haiti.

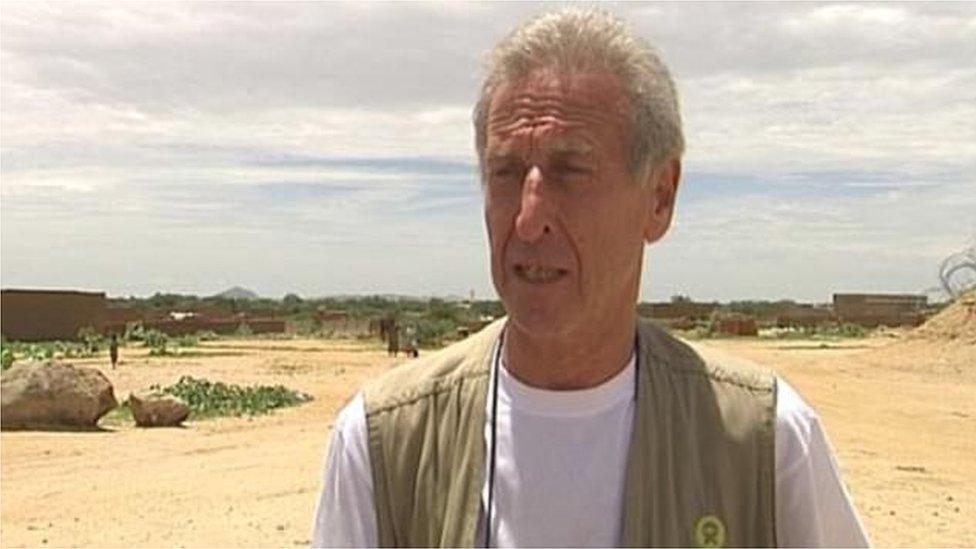

Roland Van Hauwermeiren worked in Chad in 2008 and moved to Bangladesh after his time in Haiti

"If they did that in other countries before coming here, then they're probably going to continue to do it here," she says, her frustration and anger undimmed seven years on.

Then she repeated one of the key accusations, one that Oxfam has said was unproven in its investigation into the scandal: that some of the victims were underage.

Over the past few days, I have spoken to several former Oxfam employees in Haiti. Like Josefine, they were also so concerned about the potential repercussions of talking to the press that they asked not to show their faces on camera.

Edelson, an ex-security guard at the charity, echoed her allegation about minors.

Several former Oxfam workers in Haiti were afraid to talk to me openly about the allegations, for fear of repercussions

"I can tell you for sure there were sex parties at the house," he said in carefully delivered Creole, speaking through a translator.

"Young people would often come to the office, looking for the director and I am sure these people weren't there for work. Underage girls, maybe 16, 17 years old, used to come to the office and ask for him all the time."

In part, the reaction in Haiti was initially one of resignation. The allegations against former Oxfam staff reminded many Haitians of numerous past cases of abuse and rape by UN peacekeepers.

However, that resignation has hardened to anger as more and more details of the sex scandal have emerged. Plus many Haitians in the charity sector think it is also unlikely to be limited to just one organisation.

"I'm sure that if you really ask around you would find skeletons in other organisations too," says Josefine.

Impunity is a long-standing issue in the impoverished country, and she says many foreigners have exploited that problem over the years: "There are people in these organisations who have this culture and this mentality that they can be predators and get away with it."

For some Haitian charity worker, the issues with aid agencies like Oxfam in Haiti should not be separated from the devastating earthquake in 2010.

Pierre Esperance, the head of the country's main human rights NGO, said he used to work with overseas organisations regularly before the quake. However, afterwards, he said these organisations used billions of dollars in aid money earmarked for Haiti to become "operational" and manage their own programmes without Haitian partners. He believes that a lack of local alliances has been key.

Many camps were set up after 2010's earthquake

"Oxfam, after the earthquake, became like a factory," he says over strong Haitian coffee.

"A big organisation with a lot of people and bad management. There were people who didn't have any skills regarding development, with a lot of money. And this is the result."

On Tuesday, Haiti's president, Jovenel Moise, has called the scandal "outrageous, dishonest" and "an extremely serious violation of human dignity". His staff has indicated that a full investigation of its own is imminent.

In a statement, Oxfam said it launched an investigation in 2011, "as soon as it became aware of the allegations". It denies covering up the findings, and says it has created new safeguarding policies and a confidential "whistleblowing" hotline as a result.

However, as I am talking to Josefine, the news reaches us that Oxfam's deputy chief executive, Penny Lawrence, has resigned. Josefine whistles, long and low, in genuine surprise.

Still, she wasn't going to change her mind about protecting her identity, no matter who steps down in the UK.

"This is Haiti," she reflects dryly. "Anything can happen here."

Some of the names in this article have been changed.

- Published12 February 2018

- Published12 February 2018

- Published13 February 2018