Brazil's rising tide of young conservatives seeks change

- Published

Young Brazilians, including former feminist activist Sara Winter, are embracing right-wing politics

Sara Winter has always had strong views.

As an activist, she used to chain herself to fences in protest at chauvinism and sexual violence. She was, by her own admission, one of the most high-profile feminists in Brazil.

Sara is certainly striking. She has peroxide blonde hair, tattoos and a snappy dress sense.

But the thing that stands out the most is the badge she is wearing on her top. It is a picture of a skull with a knife through it and two guns.

"It's my favourite police organisation, Bope," she says, proudly referring to the logo of Brazil's Special Police Operations Battalion.

"They climb into the favelas and kill the bad guys. They put their lives at risk all the time to save the population of Rio."

It is not the sort of comment you would expect from a liberal activist. But Sara has had a political about-turn in recent years.

'Second chance'

Six years after having an abortion, Sara became pregnant again. Between the two pregnancies, she had regained her faith in the Catholic Church and her views on pregnancy - and politics - changed radically.

"I was so happy because I felt that God was giving me a second chance to be a mum," she recalls.

"I decided to come back to the Church and I think I can help women much more with conservative politics than feminism.

"[I spent] five years being the most popular feminist in Brazil and I did nothing for women," she says. "I just spent this time talking about abortion and legalising drugs and communism and I called that empowering myself."

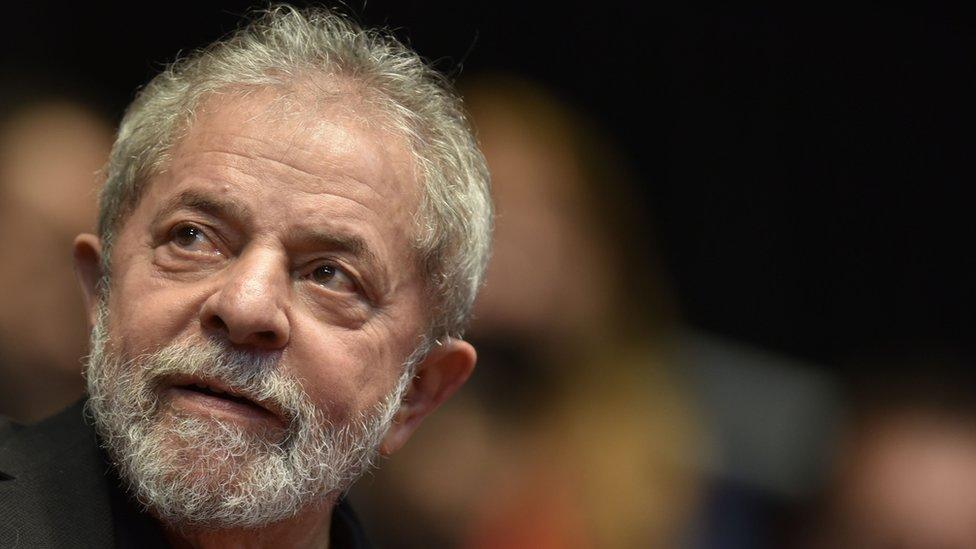

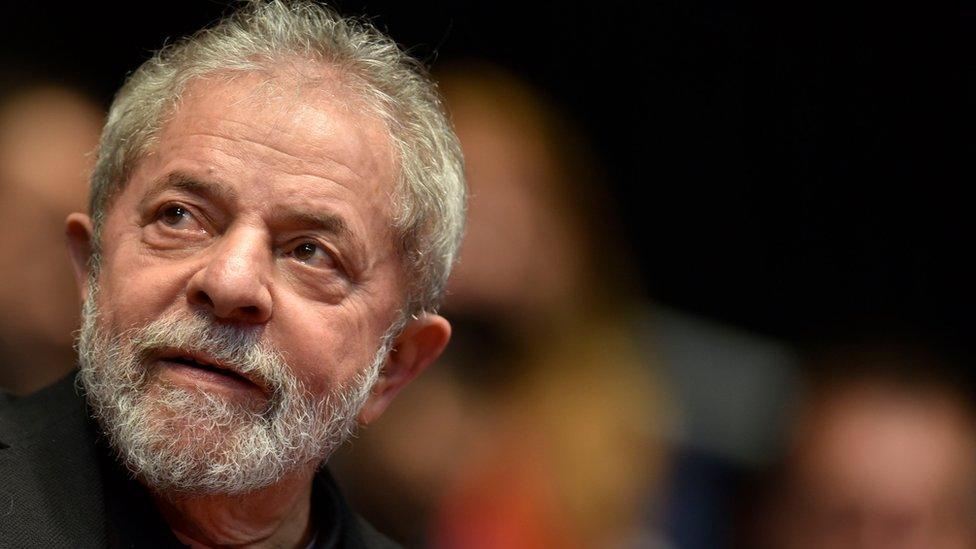

Ex-President Lula da Silva has been convicted of corruption and faces 12 years in prison

Sara's U-turn is unusual but it mirrors to some extent what is happening in Brazil.

For more than 15 years, Brazil was governed by the left. Former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva rose to power in 2003 promising change.

But with the country's most loved politician now facing 12 years in prison for corruption, and with his successor Dilma Rousseff impeached, people are disillusioned. The left did not deliver, so people want change.

'Brazilian Trump'

Sara's political idol is the far-right presidential candidate Jair Bolsonaro.

Jair Bolsonaro is currently second in the polls

Many refer to Mr Bolsonaro as the "Brazilian Trump", the two are very different men in very different countries but the similarities, or rather the set of circumstances that allow them to both exist, are uncanny.

Mr Bolsonaro brands himself as different from all the rest, a clean candidate amid a sea of corrupt politicians that has been the talk of Brazil for the past few years.

He has been accused of being homophobic and told a congresswoman she was not worth raping. He has ranted against minorities and has called for looser gun laws.

Jair Bolsonaro does not hold back.

But Sara will not have a bad word said against him. "I know it sounds really awkward, but really, if any woman could see Bolsonaro's policies, she would be in love, like me!"

She gushingly talks about one of his proposals - chemically castrating rapists.

"We have so many feminist congresswomen, why didn't they suggest this before?" she asks. "Bolsonaro did it."

Growing right

While many people wince at Jair Bolsonaro's politics, he remains a popular figure.

He is currently second in the presidential polls after former President Lula, who may not even be able to run now because of his corruption conviction.

While Mr Bolsonaro is at the extreme end of the right, conservative politics more generally are enjoying a comeback in Brazil - this in a country that until 1985 was ruled by a military dictatorship.

Right-wing pressure groups like the Free Brazil Movement, or MBL in Portuguese, are finding big audiences.

The Free Brazil Movement (MBL) emerged out of mass anti-corruption protests in 2016

The MBL started its life on the streets, calling for then President Dilma Rousseff to be impeached.

It has since strengthened by going online. It has more than 2.5 million followers on Facebook who avidly watch their political videos criticising Brazil's left-wing politicians.

The MBL calls itself libertarian. It wants a freer country with a smaller state, its way. But its politics are hard to define because most members also hold conservative views on abortion and gun ownership.

"The problem is that some parts of Brazilian mentality, especially the left-wing mentality, say that the Conservatives are always totalitarians, always on the wrong side of things," says Pedro Ferreira, an MBL co-founder.

"Whenever they try to voice what they feel they are called fascists or Nazis." He says the internet has changed things. It has allowed people to find their own voice, to find their values.

"That is why we have Trump, that is why we have Brexit, that is why we have MBL. We have the common people's voice being heard," he says.

There is widespread discontent with politics in Brazil following high-level corruption protests

"That is scaring a lot of people but that is very democratic."

Experts say Brazil's corruption scandals have been fertile ground for this kind of politics.

"You have a total mistrust of every kind of authority in Brazil, so for these movements that propagate hell, that show that everything is wrong, this kind of scenario is very useful," says Prof Rafael Alcadipani.

"They pick up very small things in reality and try to magnify them as if these were the biggest problems in Brazil."

Prof Alcadipani accuses movements like the MBL of propagating fake news. But it is an accusation the right makes against the left, too.

A wider vision of the right?

While the MBL essentially remains a movement, some of its members have entered politics on other parties' tickets.

Twenty-one-year-old Fernando Holiday may be one of the MBL's leading figures but he ran for and won a seat as city councillor in São Paulo for the Democrats party.

Fernando Holiday, 21, says that the MBL is reshaping views on the right in Brazil

An unusual poster boy for conservatism, he comes from a poor family and is gay.

He thinks young Brazilians had, until recently, become disengaged with politics.

"The right became synonymous with more conservative politics, irrelevant for minorities," he says.

"It also became associated with authoritarian, even nostalgic feelings about the dictatorship, like Bolsonaro."

"But I think we bring a wider vision of what the right is," he explains. "Not everything fits into a standard box and is determined by rigid rules."

- Published25 February 2018

- Published25 January 2018

- Published11 June 2019

- Published6 September 2017

- Published2 June 2023