Human trafficking: 350 victims rescued in Caribbean and Latin America

- Published

Operation Libertad saved victims in 13 different countries - all photos were taken on an operation in Guyana

Nearly 350 victims of human trafficking have been rescued by police in 13 Caribbean and Latin American countries.

The Interpol-coordinated Operation Libertad saved men, women and children trafficked abroad and forced into work.

Victims were found working in night clubs, factories, markets, farms and mines. Some worked in spaces "no bigger than coffins," said Cem Kolcu of Interpol's human trafficking unit.

Officers arrested 22 people and seized cash, mobile phones and computers.

The co-ordinated raids were the result of a two-and-a-half year project funded by the Canadian government, which also trained specialist officers for the team.

Police throughout the Caribbean were involved, including on the Dutch islands of Aruba and Curacao and the UK's Turks and Caicos islands, as well as in Brazil and Venezuela.

Operations were directed from Barbados and supported by Interpol command centres in Lyon, France and Argentina's capital Buenos Aires.

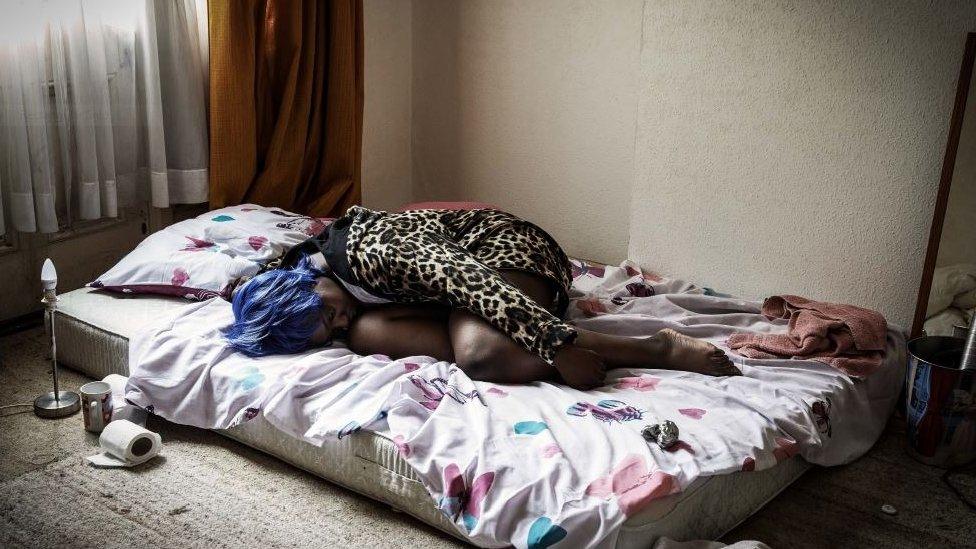

Trafficking victims are forced to work in dangerous conditions

Tim Morris, Interpol's executive director of police services, told the BBC conditions in Guyana were "particularly horrific".

There, investigators rescued young women who were forced to work as prostitutes near remote gold mines - locations from which they cannot escape and which are hard for investigators to find.

"Isolated locations make it difficult for officers to avoid detection," said Diana O'Brien, Guyana's assistant director of public prosecutions, explaining that often, by the time they can act on intelligence, traffickers have moved their victims.

Women victims were forced into prostitution in remote locations

Meanwhile, bosses at a factory in Saint Vincent and the Grenadines stripped Asian trafficking victims of their passports and forced them into total dependence, taking all their money and means of transport from them.

"To all intents and purposes, you enslave the person," Mr Morris said.

'Such a widespread crime'

Traffickers target vulnerable people seeking to cross borders for work or a better life, or even moving from a poorer to a richer region in their own countries.

Mr Morris explained that this often makes it harder to prosecute the perpetrators. "Some people don't acknowledge they are being exploited," he said, so they can continue to earn cash or stay in their new country.

Others still are intimidated into lying to investigators, complicating prosecution further.

Officers confiscated fake and real travel documents from those arrested

NGOs and social services were on hand to give support to the rescued and to ask them about their experiences to further the investigation.

"We don't just leave them be," Mr Morris said. "[Victims] get the proper social support they need."

Local authorities will decide whether to care for trafficking victims in dedicated facilities, release them or send them home.

"It all depends on the particular person's circumstances," Mr Morris said. "And often on the country's resources."

You may also be interested in:

This is one of several Interpol projects under its global human trafficking task force, which is backed by G7 security ministers.

Africa is a particular concern, although central and south America, the Caribbean and Asia all have problems with trafficking.

"It's such a widespread crime," Mr Morris said. He said the task force will operate "indefinitely" to try to eradicate the problem.

"We want to make a meaningful impact," he said, "and raise the profile of this crime."

Traffickers target those people seeking work or a better life in a new country

- Published25 February 2018

- Published3 January 2018