Venezuelans contemplate their future after Maduro's win

- Published

Venezuelans of all ages are leaving the country

The scene at Caracas bus stations tell you all you need to know about what people think of politics here. Every day, families are packing up their lives in search of some kind of future abroad.

Claudia Blanco hugs her parents tightly. Goodbyes are never easy, but if you do not know when the next hello will be, it is all the more painful.

After dropping her off at the bus station, her parents drive off, their eyes red from crying.

Ms Blanco is a 29-year-old nurse. She left Venezuela for Panama two years ago with her husband Víctor but came back to get her younger sister Coraima who has just graduated as an industrial engineer.

New life awaits

The three are on their way to the Colombian border. From there, they will travel on to Chile. They think with a strong economy, they will have more luck finding work there.

Victor, Claudia and Coraima are leaving Venezuela for what they hope will be a better life in Chile

"Our family understands," Claudia says, between tears. "They support us 100%. They know it's better to leave because there's no future for us here."

Read more about Venezuela's crisis:

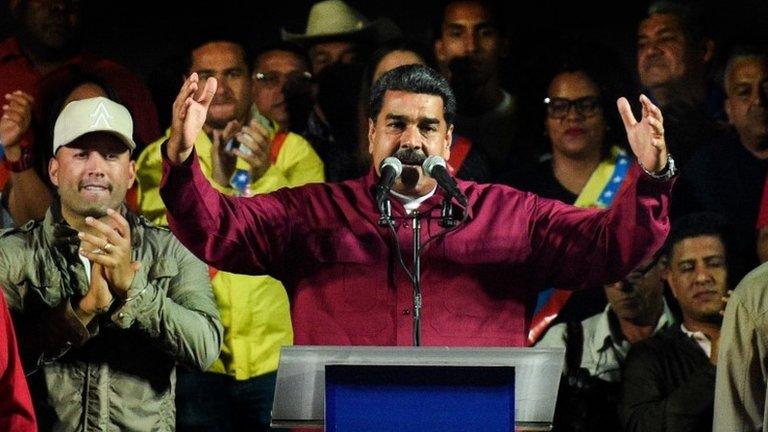

Her husband Víctor is angry about Sunday's presidential election which saw the incumbent president, Nicolás Maduro, elected to another six-year term amid allegations of fraud by the opposition. "It was a farce," he says.

Víctor says that Venezuela's economic crisis and the shortages of staple goods have affected directly him and Claudia. "We can't have a baby because we can't afford nappies or milk - we've delayed our future because of the situation here."

Destination unknown

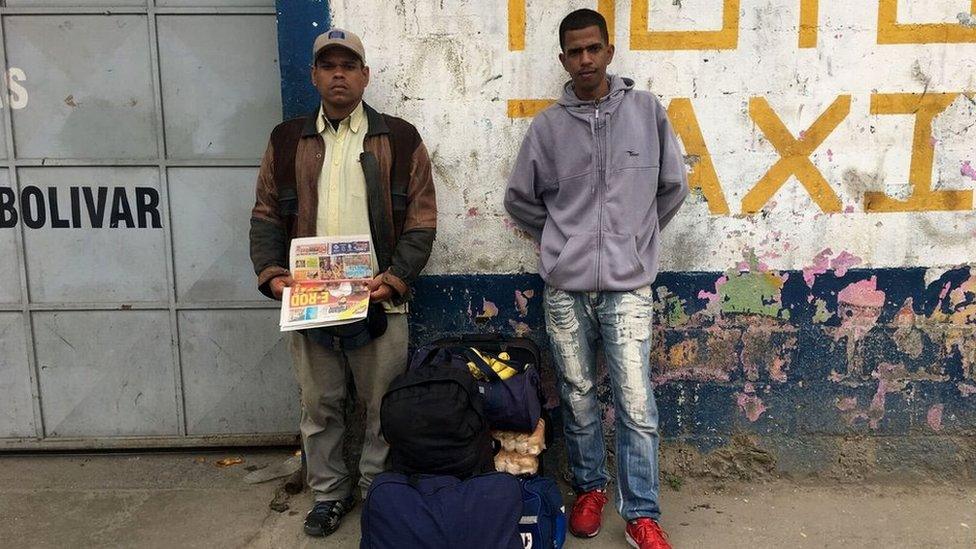

Across the road, Chreison Berros and his cousin Arturo are sitting reading the paper with their bags beside them.

Chreison and Arturo are heading to Colombia

They say that they do not know where they will go but neither do they care: they just want to head to the border but all the tickets are sold out.

I ask Chreison how he feels about President Maduro's victory. "Mr Maduro won and now we're leaving, how do you think I feel?"

He has left his mother, wife and three children behind to see if he can find work in Cúcuta, a city just across the Colombian border and the entry point for hundreds of thousands of Venezuelans leaving their country.

"The hardest part of this for me is not being able to hug my three kids - seeing pictures just isn't the same," he says.

María Becerra has been working outside the bus station for years. She has a little stand with four telephones that she rents out to people who need to make a call.

María Becerra says she has never seen so many people looking to leave the country

She says she has never seen so many people coming to the terminal.

"This isn't Narnia, this is Venezuela," she says.

"People wait for three, four, five days to get hold of a ticket. They sleep in the streets. I wish a country would come along and take them [the government] out in one go. If you kill the dog, the rabies stops."

Demise of an oil giant

While it is estimated that 5,000 Venezuelans are leaving every day, many more do not even have that option.

In a country where vast oil wealth once flowed, many people are trying to eke out a living from what is left.

The muddy grey waters of the River Guaire run through Caracas and in them, an increasing number of people searching for treasures.

Douglas Guevara sifts through the silt looking for anything valuable he can sell

Douglas Guevara has been working in this river for 14 years. "When I started, there were about six people, now with the crisis, there are 100," he says.

With the head of a broom, he scoops up handfuls of rubble from the river bed. It is thin pickings though.

There are lots of coins among the material he has got in his hand. They used to be worth something but with hyperinflation of more than 13,000%, they are probably worth less than the sediment itself.

Douglas is on the lookout for silver and gold instead. Another boy points out an earring backing he has found. It is a piece of metal that could change his day.

On a good day, Mr Guevara can earn as much as 1m bolivares. But what sounds like a fortune is only worth $1.30 on the black market.

Bleak future

With no change in government, the downward slide into greater economic and social misery is only expected to quicken and those at the bottom of the pile will suffer the most.

Groups of boys survive on the streets of Caracas by begging for food

I meet a group of boys waiting outside a pharmacy in the neighbourhood of Las Mercedes. The youngest is just seven years old.

When dusk falls, their work begins, begging for something to eat. "Lots of people used to come in their cars to drop off food," says eight-year old José Ángel.

He is wearing a baseball cap, shorts and t-shirt and has not had a wash for days. "With the crisis, fewer people can afford to be generous," he explains.

Every month their little group is joined by new boys, 10-year-old Rafael tells me. They are all friends but there are invisible boundaries here and straying across one can be dangerous.

Just a few weeks ago, one of their group was killed when he strayed into the Chacao neighbourhood. He was beaten to death. He was just 11 years old.

For a boy of his age, Rafael knows a lot about politics. "People are going hungry and Mr Maduro doesn't help them," he says. "People just vote for him for the benefits they get," he says referring to the socialist government's programmes which provide housing to the poor, among other things.

But how long those benefits will last, with international pressure and sanctions building up, is hard to guess.

What is certain though is that these little boys never had much of a future, and it is looking far less hopeful now.

- Published21 May 2018

- Published12 August 2021

- Published28 January 2019