Guatemala volcano: Search after deadly eruption

- Published

Video shows Guatemala's most violent volcano eruption in more than a century

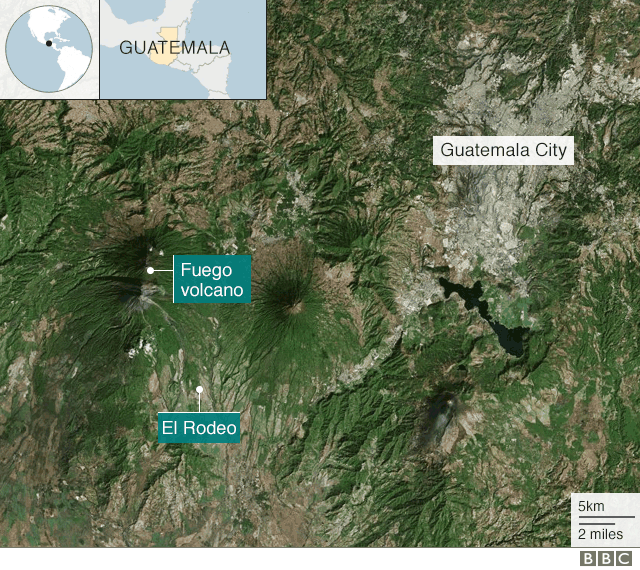

Soldiers are helping firefighters search for missing people after Sunday's horrific volcanic eruption in Guatemala, when torrents of superheated rock, ash and mud destroyed villages.

The official death toll from the destruction at the Fuego volcano has risen to 69, the authorities say.

Thousands of people are being housed in temporary shelters.

Volcanologists report the eruption, which sent ash up to 10km (33,000ft) into the sky, is over for the moment.

"It is evident that the volcano's energy has decreased and its tendency is to continue decreasing. That is to say that there will be no imminent eruption over the next few days," said the head of Guatamala's National Institute of Seismology, Eddy Sanchez.

The eruption generated pyroclastic flows - fast-moving mixtures of very hot gas and volcanic matter - which descended down the slopes, engulfing communities such as El Rodeo and San Miguel Los Lotes.

Eufemia Garcia (centre) escaped but is searching for her children

Eufemia Garcia, from Los Lotes, described how she narrowly escaped the volcanic matter as she walked through an alley to go to the shops. Though she had found two of her children alive she was still searching for two daughters and a son and a grandson, as well as her extended family.

"I do not want to leave, but go back, and there is nothing I can do to save my family," she said.

Efrain Gonzalez, who fled El Rodeo with his wife and one-year-old daughter, said he had had to leave behind his two older children, aged four and ten, trapped in the family home.

Local resident Ricardo Reyes was also forced to abandon his home: "The only thing we could do was run with my family and we left our possessions in the house. Now that all the danger has passed, I came to see how our house was - everything is a disaster."

Volcano survivor: "I think my family was buried"

Firefighter Rudy Chavez descried how he was searching affected areas for survivors and also for those who had died.

"We were about to evacuate the area when we found an entire family inside a home," he said.

" We worked to remove their bodies from the house. Someone raised the alarm that the area was very dangerous and we evacuated but thank God we met with our objective of recovering the bodies of those people."

'Day turned to night'

Jorge Luis Altuve, part of Guatemala's mountain rescue brigade, told the BBC how he and his colleagues had been up on the mountain searching for a missing person when they realised that the volcano's activity had suddenly increased.

He heard something hitting his safety helmet and realised that it was not rain that was falling but stones.

"We'd already started our descent... when the ash cloud reached us and day turned into night. From daylight it went to being as dark as at 10pm," he said.

Firefighters are searching for survivors and bodies

Soldiers were brought in to help emergency workers

Volcanologist Dr Janine Krippner told the BBC that people should not underestimate the risk from pyroclastic flows and volcanic mudflows, known as lahars.

"Fuego is a very active volcano. It has deposited quite a bit of loose volcanic material and it is also in a rain-heavy area, so when heavy rains hit the volcano that is going to be washing the deposits away into these mudflows which carry a lot of debris and rock.

"They are extremely dangerous and deadly as well."

What is a pyroclastic flow?

By Paul Rincon, science editor, BBC News website

A pyroclastic flow is a fast-moving mixture of gas and volcanic material, such as pumice and ash. Such flows are a common outcome of explosive volcanic eruptions, like the Fuego event, and are extremely dangerous to populations living downrange.

Just why they are so threatening can be seen from some of the eyewitness videos on YouTube of the Guatemalan eruption. In one, people stand on a bridge filming the ominous mass of gas and volcanic debris, external as it expands from Fuego.

Some bystanders only realise how fast it is travelling as the flow is almost upon them.

The speed it travels depends on several factors, such as the output rate of the volcano and the gradient of its slope. But they have been known to reach speeds of up to 700km/h - close to the cruising speed of a long-distance commercial passenger aircraft.

In addition, the gas and rock within a flow are heated to extreme temperatures, ranging between 200C and 700C. If you're directly in its path, there is little chance of escape.

The eruption of Vesuvius, in Italy, in 79 AD produced a powerful pyroclastic flow, burying the Roman towns of Pompeii and Herculaneum under a thick blanket of ash.

Are you in the area? Share your experiences by emailing haveyoursay@bbc.co.uk, external.

Please include a contact number if you are willing to speak to a BBC journalist. You can also contact us in the following ways:

WhatsApp: +447555 173285

Tweet: @BBC_HaveYourSay, external

Send pictures/video to yourpics@bbc.co.uk, external

Send an SMS or MMS to 61124 or +44 7624 800 100

Please read our terms and conditions and privacy policy

- Published4 June 2018

- Published4 June 2018

- Published27 May 2018