Guatemala's Fuego volcano: How the tragedy unfolded

- Published

Guatemala's Fuego volcano erupted at about noon local time (18:00 GMT) on Sunday.

It is one of Central America's most active volcanoes but Sunday's eruption caused more fatalities than any of those previously recorded at Fuego.

At least 69 people are known to have died.

Most of them lived in villages on the slopes of the 3,763m-high volcano and were killed by what is known as pyroclastic flow, a searing cloud of debris.

What type of volcano is Fuego?

Fuego is a stratovolcano or composite volcano. Its steep, conical shape, which is typical of this type of volcano, can be seen from the capital, Guatemala City, 44km (27 miles) south-west of Fuego's summit.

Fuego is a stratovolcano

Fuego sits on the Ring of Fire, a horse-shoe-shaped string of volcanoes, earthquake sites and tectonic plates around the Pacific, which spreads across 40,000km (25,000 miles) from the southern tip of South America all the way to New Zealand.

Stratovolcanoes are usually formed over a period of tens to hundreds of thousands of years and commonly produce highly explosive eruptions.

Fuego regularly erupts but usually these are smaller events which pose little risk to surrounding villages.

So what happened this time?

Stratovolcanoes are made up of alternating layers of lava, ash and rock.

When a stratovolcano erupts, the rock layer is smashed into tiny dust particles.

Video shows Guatemala's most violent volcano eruption in more than a century

These particles mix with the hot ash and gases to form a giant cloud.

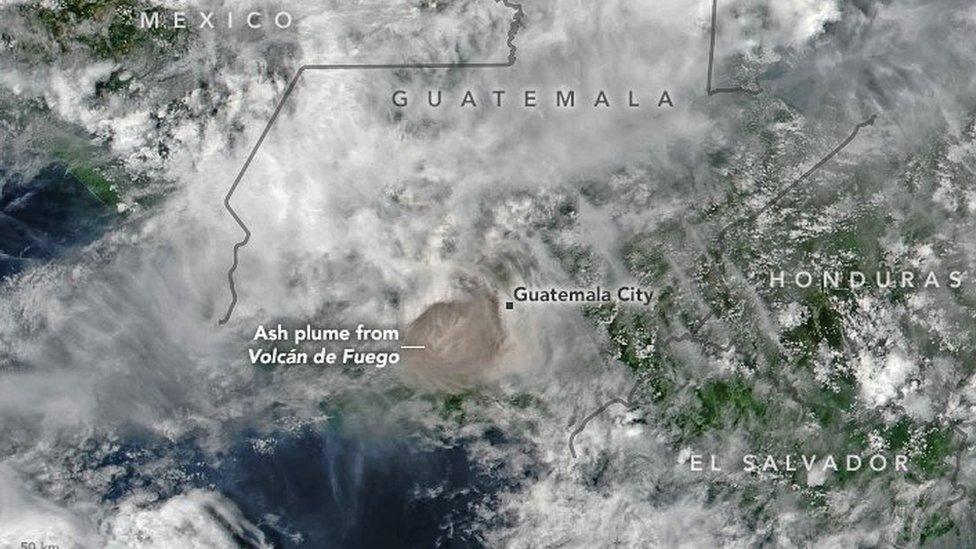

Volcanologists say the ash plume from Fuego reached a height of 10km (33,000ft). It could be clearly seen from space, as this image taken by Nasa shows.

Nasa's Earth Observatory published an image of the ash plume seen from space

As the eruption weakened, the ash cloud collapsed under its own weight and cascaded down the side of the volcano as a pyroclastic flow.

Pyroclastic flows contain a high-density mix of hot lava blocks, pumice, ash and volcanic gas. They move very quickly down volcanic slopes, typically following valleys.

Fuego's pyroclastic flow is the reason why so many people died in the volcano's most recent eruption compared to the last major eruption in 1974, when no deaths were officially recorded.

They can reach a speed of up to 700km/h (450mph) and are considered to be the most deadly volcanic event because they are impossible to outrun and can travel for miles.

Temperatures inside pyroclastic flows can range between 200C and 700C (390-1300F) and can ignite fires. They destroy everything in their path.

How did residents respond?

Locals living on the slopes are used to smaller eruptions but the virulence of Sunday's event caught them by surprise.

Aerial photos show the path of destruction created by the pyroclastic flow

Many of the victims were found near their homes, indicating that they did not have time to flee. Others managed to save themselves but are still searching for members of their families.

The villages worst affected were San Miguel Los Lotes and El Rodeo. Aerial photographs show how they were covered by pyroclastic flow which rushed down the slopes of the volcano.

Video footage showing people gazing at the pyroclastic flow coming down the mountainside, external suggests they were not aware of how fast it spreads and the danger it poses.

Continuing risk

Volcanologists warn that while the eruption has seized for now, the danger is not yet over. If heavy rain were to fall on Fuego's slopes, it could cause deadly mudslides carrying ash, boulders and debris down the mountainside.

The Guatemalan authorities calculate that 1.7 million people have been affected by the eruption and large areas remain covered in ash.

Houses and trucks were covered in ash in Escuintla, to the south of the volcano