Peru's Amazon: Where roads change lives

- Published

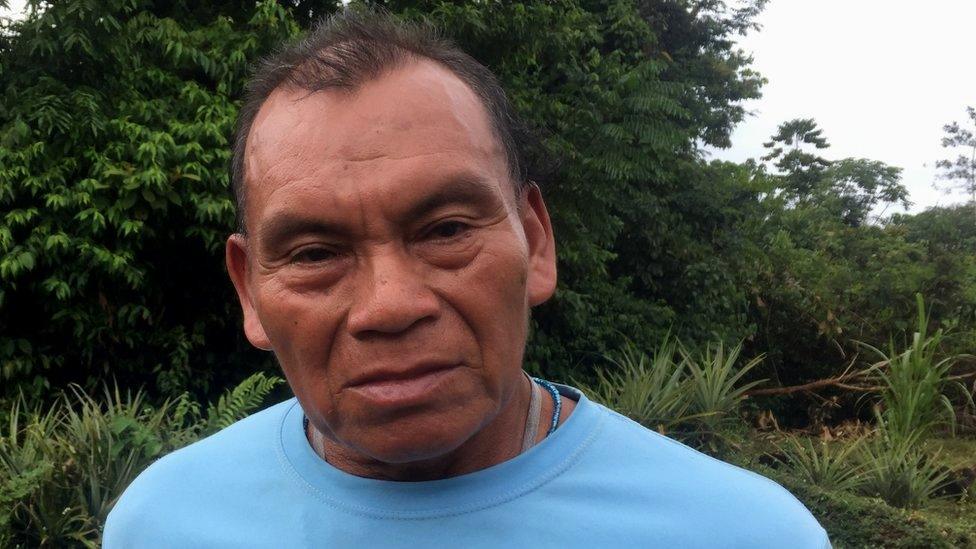

The new road is good news for farmer Raúl Andrés Condori Ypanki

Raúl Andrés Condori Ypanki sits on the veranda of a wooden house, sipping coffee, with the television blaring in the background.

He is a small-scale farmer with 15 acres of banana plants who moved to this Amazonian region of Madre de Dios 22 years ago. In the past few years, the local government has built a new road that connects this informal settlement, Puerto Shipetiari, with the nearest town, Salvación.

"Thanks to the construction of this road, the lives of local people have changed," he says.

Local shops have benefitted from the road

"Before they lived in extreme poverty. Now everyone who lives alongside this river can sell their agricultural products. Traders have come with their cars and they buy their goods. Tourists come and buy fruit and other things. We farmers live from agriculture and trade."

Unexpected consequences

Across the muddy Madre de Dios river lies the indigenous community of Shipetiari, where 24 families harvest Brazil nuts and grow bananas, yucca and maize.

Shipetiari used to be very isolated but with the new road came new challenges

Canoes used to be the main mode of transport

Romelia Rivera Italiano teaches at the community's small school. She originally supported the idea of the road, but, she says, it has led to an influx of people, some of whom have encroached on their communal lands.

"They have been cutting down trees illegally when they should be conserving the forest," she says.

Ms Rivera says the growth in population has even changed the way of life within the indigenous community,

"Before, we shared everything, we helped each other, we ate together. Now each person just works on his own farm," she said.

Romelia Rivera Italiano says she initially supported the road but has since changed her mind

Mateo Augusto Mavite said there has been an influx of people since the road was built

Mateo Augusto Mavite is president of the Shipetiari indigenous community. He, too, says that the road has brought unexpected consequences.

"Before it was built we thought the road was a good idea," he said.

"We thought it would help us sell our agricultural goods. We thought it would be helpful in medical emergencies and improve the education of our children, but we didn't realise the impact it would have. Lots of people have come to live here. Some of our people have been threatened."

Roads as political football

Amazon roads are a political battle in Peru. When the environment ministry objected to the local governor building a road here, the opposition-controlled Congress passed a law supporting it. The law called for the road to be extended deeper into the rainforest to Boca Manu and Boca Colorado.

The road makes it possible for timber lorries to reach Puerto Shipetiari

The president of Peru at the time, Ollanta Humala, formally objected to the law in December 2015 and it was eventually shelved, but satellite images suggest the road continues to be extended regardless.

Congress has since passed an even more controversial law calling for road building in one of the most remote areas of the Amazon, in Ucayali state on the border with Brazil.

The law states that it is a "national priority" to build roads in this frontier region.

It was ratified by Peru's president in January 2018 despite concerns expressed by the ministries of environment and culture that it could affect several national parks and uncontacted indigenous tribes.

But this does not mean that it is automatically legal to build roads in Ucayali. Any construction project still needs to comply with legislation to protect indigenous rights and the environment.

Roads as a matter of life and death

Congressman Carlos Tubino, who represents the state of Ucayali, is a prominent supporter of the road-building law.

Carlos Turbino says balance is needed between connecting remote communities and protecting the environment

"We need to protect biodiversity, but we also need to be aware that in these areas of Peru there is a lot of poverty," he says.

"There are people who die because of the lack of connectivity, people who die of simple medical problems.

"We have to strike a balance and say, OK, we're going to conserve these forests as best we can, but not at the cost of extreme poverty, chronic malnutrition, lack of education and disconnection from the rest of the world," he argues.

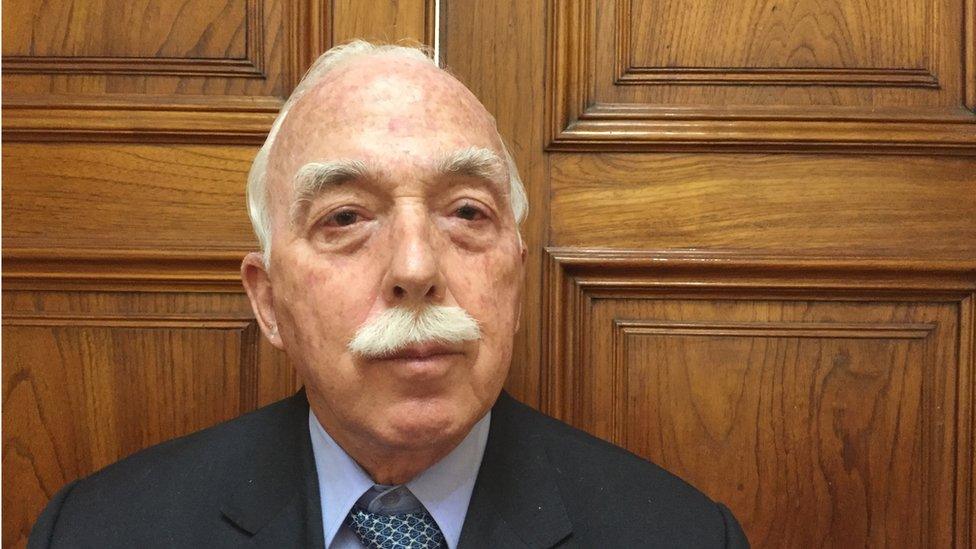

But Lizardo Cauper, president of the Inter-Ethnic Association for Development of the Peruvian Rainforest which represents all the indigenous groups of the Peruvian Amazon, says roads have not helped local people.

Lizardo Cauper says experience shows that roads lead to the destruction of forests

"Roads are synonymous with all types of impacts on human rights and collective rights," he says.

"From all our experience in Madre de Dios and other parts of the Amazon region, they haven't meant development, they have only meant the destruction of the forest," he warns.

"In some areas we have seen illegal mining. Roads have also led to an influx of other actors such as drug traffickers and people traffickers."

Anyone seeking to build a new road in the Amazon will still need to seek approval from the ministry of the environment but local politicians who start building illegally often find support among small farmers, like Mr Condori, who insist that new roads have transformed their lives.

- Published19 January 2018

- Published20 July 2018

- Published20 April 2018