Nicaragua crisis: The people caught in the middle

- Published

Nicaragua is in crisis. During five months of anti-government protest and the government crackdown that followed, hundreds of people have been killed. Local photographer Carlos Herrera has been on the streets to see how the unrest has been affecting people.

'It was like a pressure cooker'

"It was like a pressure cooker. We exploded after living under an authoritarian government," says Reyna Rodríguez, who has joined the protests in the country's capital, Managua.

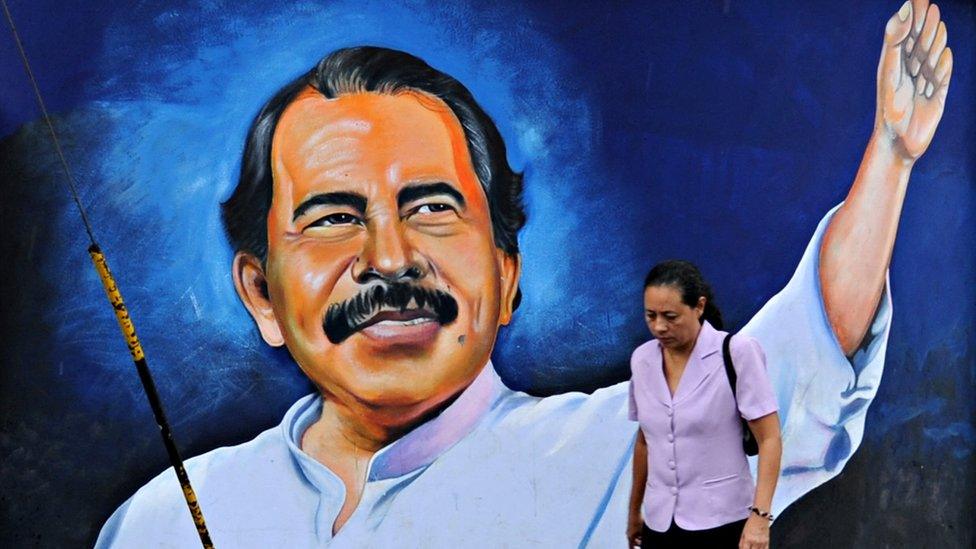

Demonstrators - who often dress in blue and white, the colours of the national flag - are calling for an end to the government of President Daniel Ortega.

They first took to the streets in April, with the more modest aim of wanting to see pension reforms rolled back, but their discontent became more vehement after 30 people were killed during those five first days of clashes.

Ms Rodríguez says she decided to join what she calls the "fight for freedom" after seeing so many young people among the dead.

Since that first week, the death toll has continued to rise. Pro-government militia have been blamed for much of the violence. The masked groups have been seen roaming the streets, dismantling demonstrators' roadblocks, firing live ammunition and making arrests.

President Ortega has denied backing the groups, but he told Euronews that "volunteer police" are sometimes masked. He insists the protests are being led by terrorists who want to stage a coup against him.

Of the pro-government gangs, Ms Rodríguez says: "If we stop, they win. If we separate, they will be sent after us. But if we stand together, they can't kill us."

'Sandinistas want peace'

State employee Edy Luz Tellería Lanuza is a long-time supporter of the governing left-wing Sandinista Liberation Front (FSLN) and its leader, President Ortega.

The arts teacher says the violence has been driven by "right-wing vandals and coup-mongers, being supported by drug traffickers, gangs and imperialists", which is what the government also says.

At least 22 police officers died between April and July, according to the UN.

Ms Tellería Lanuza says protesters are creating instability in the country, a culture of hate on social networks and grief in Nicaraguan homes.

"We had peace," she says of Nicaragua's recent decades, following civil war in the late 1970s and 1980s. "Comandante Daniel Ortega has been doing a good job with the right-wing opposition - but that's now ruined."

Mr Ortega originally rose to power off the back of the left-wing Sandinista revolution, which was launched to bring down the Somoza dynasty, but later also defeated the rise of US-sponsored rebels, the Contras. He served one term as president from 1984, but then lost his bid for re-election numerous times before regaining power in 2006.

"We want want peace. We want Nicaragua to be free," says Ms Tellería Lanuza. "Just as long as no one tries to eliminate Sandinismo. Our children will be Sandinistas, our grandchildren will be Sandinistas. Sandinismo will never end. Viva la revolución!"

'They are rounding people up'

Elizabeth del Rosario Cano Molina holds up a picture of her detained husband

Elizabeth del Rosario Cano Molina is a 20-year-old textile worker. In July, her husband, a barber in the central city of Diriamba, was on his way to work when he was captured by hooded paramilitaries.

When shooting broke out, she says, Henry López Mora got caught in the middle. He is not a follower of any political party and only intervened to help a drunk man move out of the line of fire, she says.

Mr López Mora is being held in El Chipote prison in the capital, Managua, where detainees are reportedly being tortured, according to accounts collected by the UN, external. President Ortega has insisted the report is biased and ignored attacks by protesters on members of the governing Sandinista party. He has expelled the investigators from the country.

People gather outside the jail daily, waiting for information on relatives, many of whom are unaccounted for.

"I have faith in God that he is ok," says Ms Cano Molina, who is pregnant with the couple's first child. "No one tells me anything. I wanted to pass some clothes to him. They won't even let me give him some flip-flops."

"It is a lie that they are peaceful," she says of the paramilitaries. "[They] are rounding up people as if they were enemies. One day when I was coming back from work, a boy came up to me and asked me to protect him. I asked him what was going on and he said: 'Those men want to take me'.

"Maybe he was not taken because they saw him with me."

'The country is sliding backwards'

"All I want is peace and normalcy," says Mendieta Murillo, a small businessman from the Masaya area, who does not not support any political party.

The city of the Masaya was a stronghold of the protest, brought to a standstill by roadblocks built by anti-government supporters. After violent clashes, the government declared it back under state control in July.

Mr Murillo says that from his town, Nindirí, it was impossible to get into the city centre, which hugely impacted lots of small traders. "When they put up roadblocks, they charged people to pass. That is not right. That won't bring about change. Dialogue is what is needed."

He supports peaceful marches, but not the roadblocks or the violence. "It's making the country slide backwards... We are all Nicaraguan brothers. We should not be killing each other."

'We are killing all our young'

"Claudia" is scared to show her face or give her real name, out of fear of repercussions. However, she says she wants the world to know that she cannot be silenced.

She is vehemently opposed to President Ortega and his wife, Rosario Murillo, who is also his vice-president. They are the real terrorists, she says, not the protesters.

She is convinced that the only solution is for the couple to step down. She would even welcome an intervention from US President Donald Trump.

"At this rate we are going to kill all our young people," she says, noting that the protests have been largely student-led. "We are nothing without our students, nothing. We need to let a free Nicaragua shine again."

All photographs by Carlos Herrera and subject to copyright.

- Published1 September 2018

- Published6 August 2018

- Published16 July 2018

- Published10 January 2022

- Published19 July 2018

- Published31 December 2024