Colombia hopes a referendum will help root out corruption

- Published

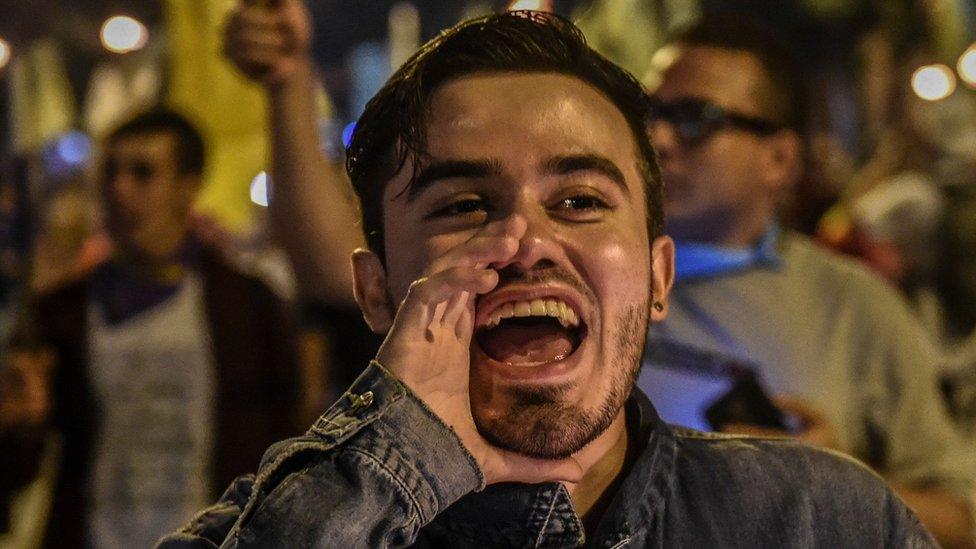

Supporters of the referendum hope for a turnout of 15 million voters

Mention corruption and most Colombians will agree that it is a massive problem.

Fifty trillion pesos ($16.8bn, £13bn) have been lost from public resources to corruption, according to Colombia's comptroller general, Edgardo Maya Villazón.

There have been attempts to tackle the problem through laws, more thorough investigations and even by raising public awareness through campaigns.

On Sunday, Colombia is going to try something different. Voters will head to the polls in a referendum that its supporters hope will bring about tougher anti-corruption legislation.

But even though polls suggest that corruption is Colombians' top concern a "yes" vote is not a foregone conclusion by any means.

What are people being asked?

Voters will be asked whether they agree to seven measures:

Recent corruption scandals have re-ignited the debate on the issue

1. A pay cap limiting salaries of members of Congress to 25 times the national minimum wage

2. That individuals convicted of corruption serve their full sentence in jail

3. That public entities be open and transparent when hiring contractors

4. Letting citizens have a say on the budget

5. Require members of Congress to be open about which bills they proposed, how they voted and who lobbied them

6. For elected officials to disclose their assets, income, and the taxes paid

7. To restrict elected officials to three terms in the same legislative body

What happens next?

Congress has one year to write the proposed measures into law

The referendum is binding but it is only valid if a third of all voters take part - just over 12 million.

For each individual measure to be adopted, it needs to receive 50% of valid votes plus one.

Congress then has one year to turn the measures into law and make them legally binding. If that does not happen, the president has 15 days to do so through a decree.

Can the measures really curb corruption?

Non-governmental organisation Transparency for Colombia, says some of the proposed measures would go some way towards rebalancing the ethical relationship between elected officials and the people.

Despite adopting international norms, there is no evidence that Colombia has successfully curbed corruption according to recent research

But the country's prosecutor-general, Nestor Humberto Martinez, said the steps were "limited and insufficient".

He has called on President Iván Duque to appoint special anti-corruption judges to handle the growth in the number of corruption cases.

Senator Claudia López - one of the proponents of the referendum - argues that the initiative was "not intended as the sole solution against corruption".

"We need political-electoral reform and judicial reform. But [the referendum] is a start," she said.

Who opposes the measures in the referendum?

All parties say they support fighting corruption - the referendum bill cleared the Senate with an impressive 84-0 vote.

However, six out of the seven questions had previously been introduced in Congress and defeated in the lower chamber.

Transparency International says people's voices 'have been heard' on corruption

Germán Manga, a columnist with weekly Semana, has called the questions "irrelevant, anodyne, almost childish".

He says most of the measures proposed are already covered by current laws.

Joaquín Vélez Navarro, a columnist with El Tiempo, has branded the proposals "pure populism".

His criticism of the referendum includes an attack on the measure to cut the salaries of state officials - which in his view could backfire.

"Such a law could generate incentives for some officials to 'adjust their salaries' through corruption. Or they could put off honest people from dedicating their professional life to public service."

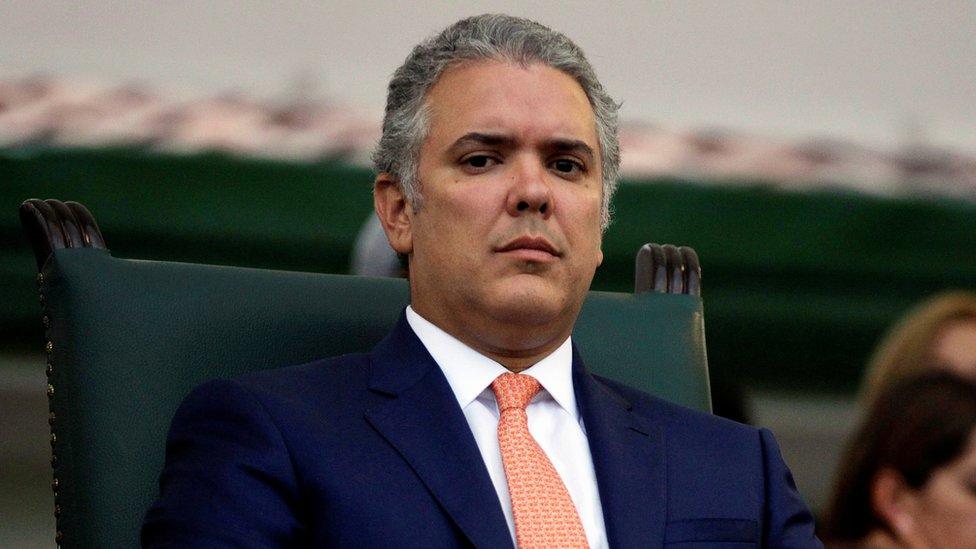

President Iván Duque entirely eschewed the issue in his inauguration speech on 7 August.

Two days later, he presented to Congress a package of four legislative bills aimed at fighting corruption - three of which were included in the points of the referendum.

Mr Duque now says he will vote on Sunday - but his governing Democratic Centre party is not actively campaigning for it.

Will the referendum succeed?

Supporters of the referendum want voters to come out in numbers exceeding 15 million. But that turnout will not be easy to achieve.

Last June, 19.5 million - or 53% of voters - took part in the second round of presidential elections but turnout at elections tends to draw many more voters than referenda.

Meanwhile, Colombian social media is awash with fake news aimed at undermining the vote.

Newly elected Colombian President Iván Duque, says he will vote in the referendum

One widely circulated myth is that the proposal to lower the salaries of members of Congress would result in a pay cut for ordinary Colombians and pensioners.

"Many [people] are trying to discredit the referendum with fake news," Ms López tweeted. "Do not believe in lies!"

She has urged voters to come out to support the proposals.

"The referendum would be unnecessary if they didn't steal 50 trillion [Colombian pesos] from us."