Left behind: How Venezuela crisis is tearing families apart

- Published

After a mass exodus of 2.3 million, many Venezuelan families can only communicate via phone

According to United Nations figures, 2.3 million people left Venezuela between 2014 and up to June 2018. Thousands continue to flee.

With 7% of the population having left nearly every family has been affected.

Development charity Cafod, which forms part of Caritas International, has spoken to some of those left behind.

María Teresa Jiménez, 85

A retired seamstress and mother of nine, María Teresa Jiménez has watched five of her children and nine of her grandchildren leave Venezuela.

"I worked for 38 years as a seamstress, and it went very well, my children wanted for nothing. Now, we don't even have money for medicine," she says of the shortages which have hit Venezuela for the past years.

Read more about Venezuela's crisis:

"Fortunately, I didn't have my children now, I had them at a time when they could succeed.

"I'm happy that my children are in a place where they don't face danger. I wish I were 20 years younger, so I could go with them."

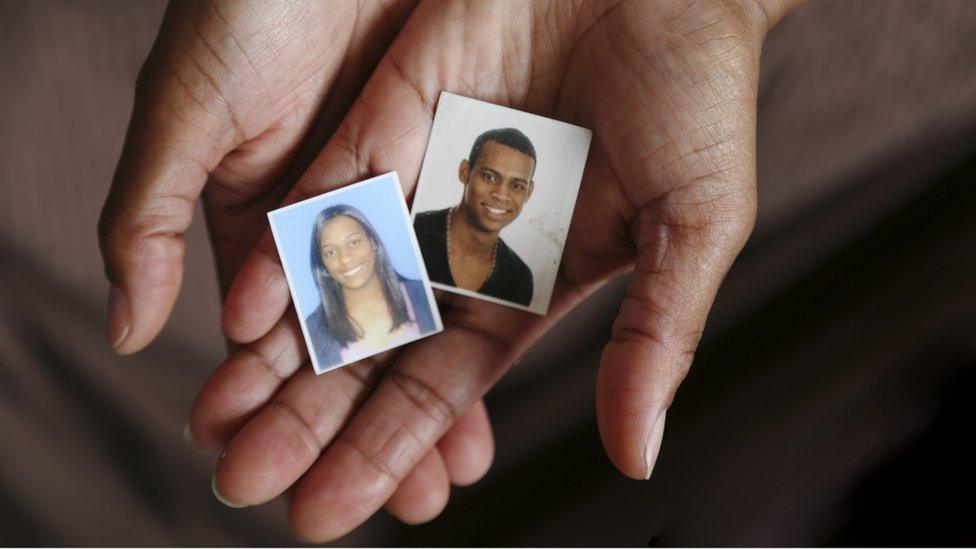

Magaly Henríquez, 58

Magaly Henríquez is a mother of five. She has stayed behind while her two youngest children, María Eugenia, a special education teacher, and Junior, a businessman, have immigrated. "It is really painful," says Ms Henríquez.

"My son had so many dreams. He started a paint supply business (which was forced to close due to rising prices). My daughter was working two jobs, and that wasn't enough for her to survive here. Many of the teachers in Venezuela had to leave."

Junior has now found work in Peru as a physical trainer and María Eugenia works as a housekeeper.

"I grew up in a free Venezuela," says Ms Henríquez "We didn't have these limitations with money. We could afford things. We had what we needed to live."

Maribel Pérez, 62

Ms Pérez has been caring for her grandchildren Naile, 12, Naiberli, 7 and Naire, 13, for a month, after her daughter went to seek work in Colombia.

"She'd been looking for work for over two years and nothing. I told her to take advantage of the fact I still have the strength to look after them," says Ms Pérez.

"It's hard on the girls. They've had birthdays, graduations and their mum isn't there. But when she calls they just tell her not to worry that they are fine and love her very much."

School enrolment is fast approaching, and registration requires that each child submits ID photos. The photographs cost a little more than a quarter of the average monthly salary.

If she doesn't get the images taken the girls will not be able to go to school.

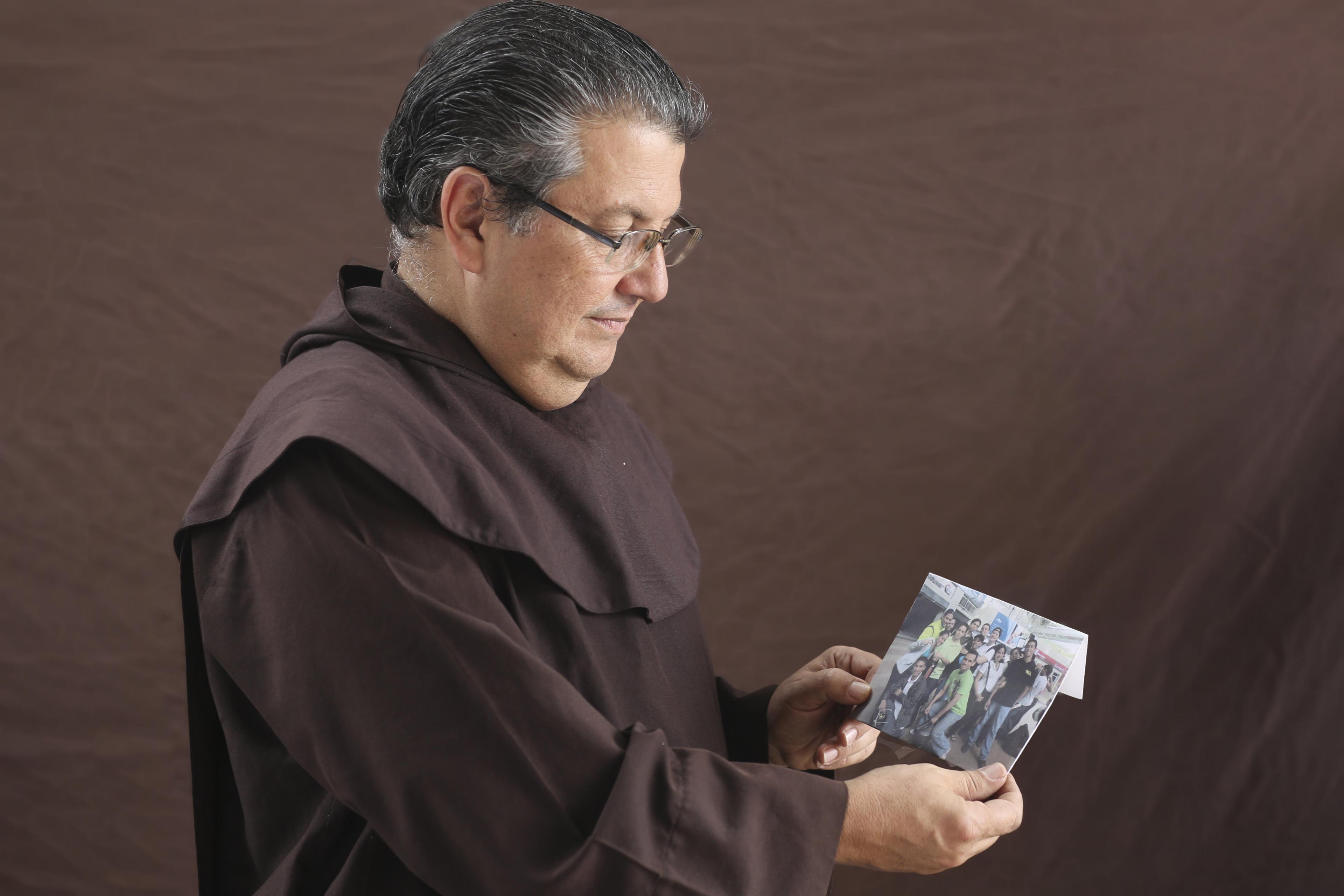

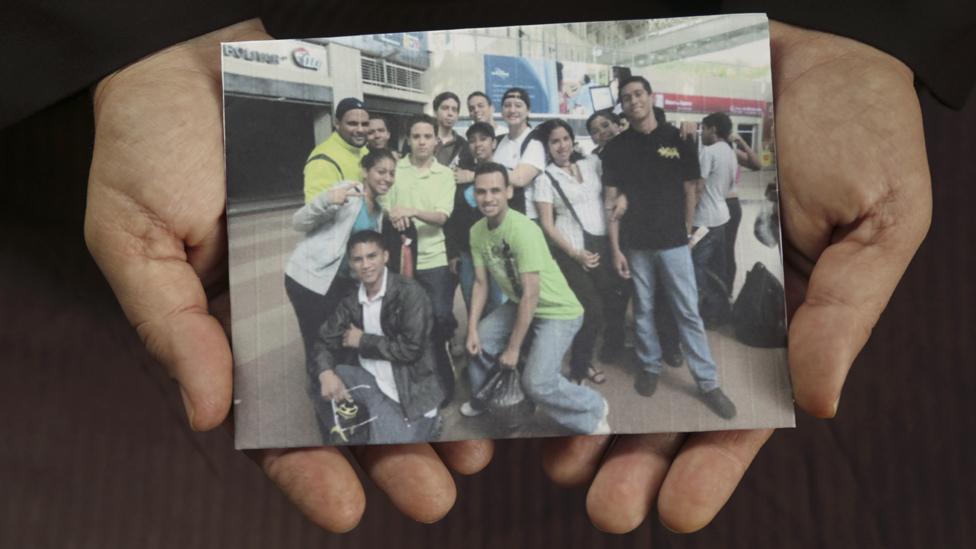

Father Cristóbal Domínguez

Fr Cristóbal Domínguez has seen a mass exodus of youth from his parish - in the first half of the year, 17 youth ministry members migrated.

"We suffered the loss of the entire parish choir, which was made up of young adults who migrated last December," he says.

"We're now trying to form a new choir, but the topic of conversation is always about what other countries they can go to, which one offers more opportunities.

"Sadly, many of them feel that to find brighter horizons their only option is to migrate."

Working alongside Caritas Venezuela, Fr Cristóbal's parish runs an "olla comunitaria", a soup kitchen providing food for more than 500 people every week.

With the new school year only weeks away, he fears that many classes will be without teachers as they will have migrated.

All photographs by Caritas International.

- Published26 August 2018

- Published25 August 2018

- Published25 August 2018

- Published22 August 2018