Mexico students v the state: Anniversary of 1968 massacre reopens recent wounds

- Published

The plaza where the students were killed as it looks today

Student leader Myrthokleia González was addressing the crowd in the square from an apartment balcony when she heard the first shots. She thought they were blanks at first and tried to calm the panicking protesters below. But Ms González realised what was happening when she saw the first activists drop.

Fifty years on, the Mexican media is paying tribute to the student protesters who died during the 1968 Tlatelolco protests in Mexico City. The death toll has never been clear: an official report from the time put it at 26, while student leaders estimated it at 190.

However, last week a Mexican government body finally recognised the state was behind the massacre - something many Mexicans had insisted for years.

The anniversary of the 2 October killings has also raised uncomfortable questions for the outgoing administration, which has been accused of other rights abuses.

"Similar situations are still happening," Ms González told the BBC. "Although many things have improved, we still see terrible human rights crimes in Mexico."

Ms González, then aged 22, was a member of the National Strike Council, the student collective that brought some 4,000 activists to the Plaza de las Tres Culturas in the capital's Tlatelolco district that evening.

The students wanted the government to free political prisoners and respect their right to protest.

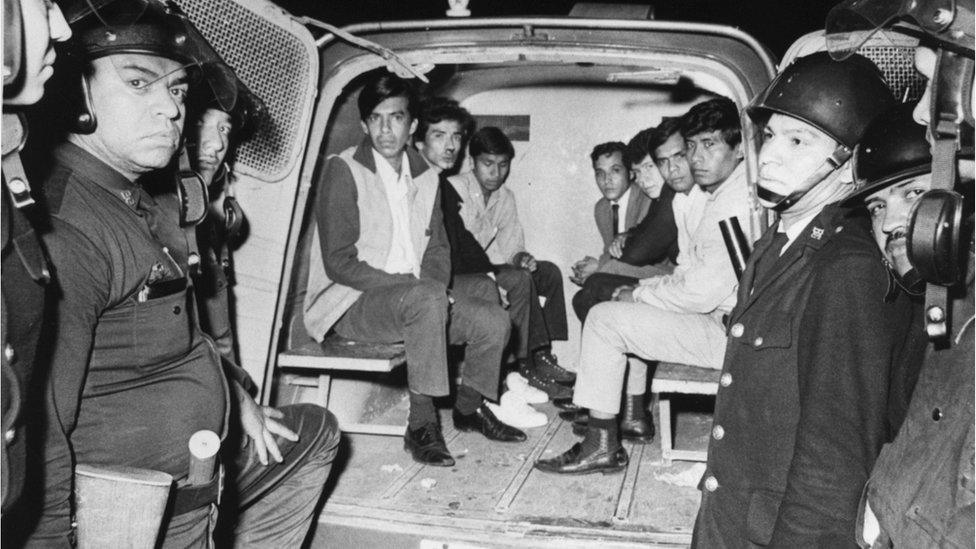

Police in 1968 show off a van full of captured students in Tlatelolco

But authorities feared the student movement would disrupt the Olympic Games, which Mexico hosted 10 days after the massacre.

The ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI, had kept a tight rein on the country for nearly four decades. Its politicians have been accused of controlling the press and manipulating elections to keep opposition parties out of power.

A new president will take over in December and will be under pressure to deliver on campaign promises to transform the country.

No one has ever been jailed for the government's brutal treatment of students in 1968.

A state crime

After the massacre, authorities said leftist radicals in surrounding buildings had shot down at soldiers in the square, prompting them to return fire.

But half a century later, a government official finally called the Tlatelolco massacre a "state crime".

Last week, Jaime Rochín, the head of the Executive Commission for Attention to Victims, said the government used "snipers who fired to create chaos, terror and an official narrative to criminalise the protest".

A monument to the students stands in the plaza

In 2006, the United States' National Security Archive (NSA) released records confirming 44 deaths, although many eyewitnesses believe the toll was higher.

The NSA has also revealed that the US government played a role in the tragedy. Declassified cables show the Pentagon gave Mexico weapons and ammunition to quash unrest.

Arrests and hunger strikes

The repression also continued after the massacre. Security forces arrested more than a thousand survivors. Ms González was held for more than a week in police cells before she escaped during a hospital transfer.

Male student leaders were held in Mexico City's Lecumberri prison. Many inmates launched a six-week hunger strike in protest at their treatment. In response to the strike, prison authorities encouraged other convicts to attack the students with pipes and sticks.

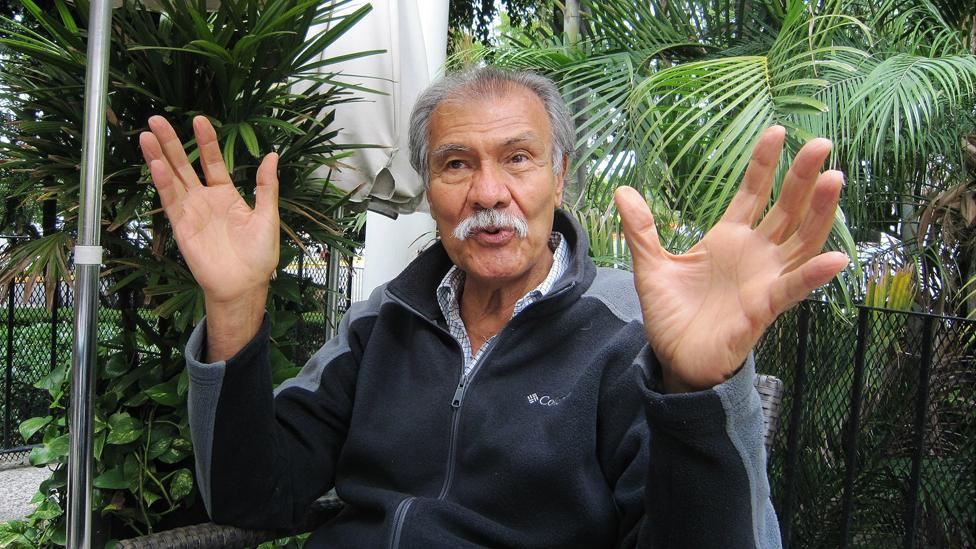

Student leader Salvador Ruiz spent two years in the prison. He disagrees with analysts who say the movement led to more freedom of expression in Mexico.

Salvador Ruiz still lives with the memories of that night

Although major reforms allowed new political parties to register within a decade, Mr Ruiz doubts the student protests were behind that change.

"After the movement, society became more urban and open," he told the BBC. "These changes would have still happened without the massacre."

Mental images of the wounded and trampled have stayed with him through the years. Today, he looks back and sees that night as an unmitigated tragedy.

"If we don't accept we were terribly defeated, we won't find a path for the future," he said.

The missing 43

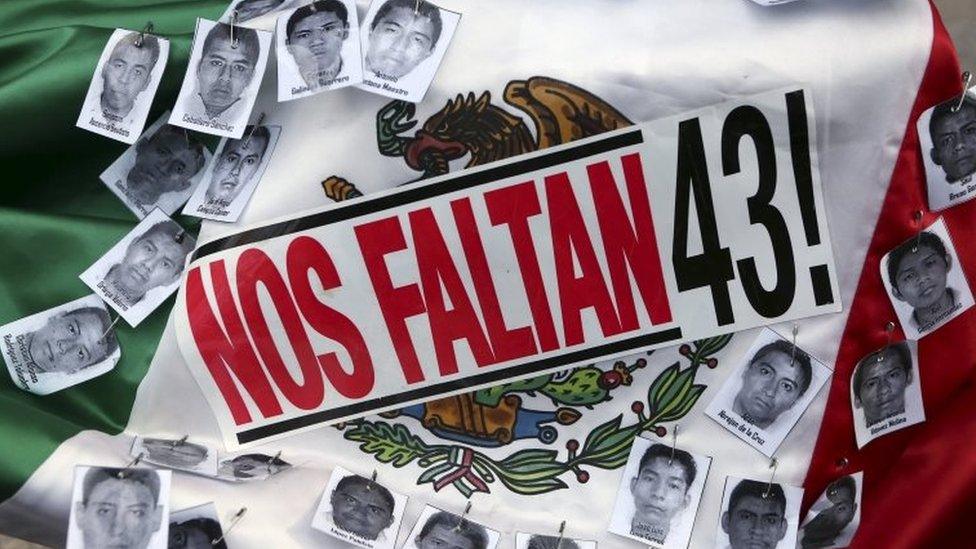

Mr Ruiz is proud that his generation inspired later protest movements in Mexico. But his despair deepened in September 2014, when news broke that 43 activists from Ayotzinapa Teachers' College had disappeared in the southern state of Guerrero.

Mexicans are still calling for information on what happened to the 43 Ayotzinapa students

The incident highlighted the ongoing dangers for young activists in Mexico, especially as the students were heading to the capital for the anniversary of the Tlatelolco massacre.

Authorities said police and gang members abducted and murdered the group.

But relatives, protesters and international investigators said the state probe was flawed. They accused the state of ignoring calls to investigate the army's possible involvement.

"The Ayotzinapa and 2 October incidents were both state crimes," said Celia Flores, another Tlatelolco survivor.

Ms Flores worries young Mexicans are now at greater risk than in the past. Since the government sent troops to fight the country's drug cartels in 2006, waves of violence have left more than 215,000 dead.

The Ayotzinapa disappearances drew attention to the links between the state and organised crime.

Protests were held in Mexico on the fourth anniversary of the Ayotzinapa disappearances on 26 September

Despite these dangers, Ms Flores has not discouraged her 31-year-old son, Ernesto Cruz, from dedicating himself to activism.

Mr Cruz has campaigned alongside relatives of the 43 missing students.

In 2014, a police officer fired a tear-gas canister at his face during preparations for a concert in solidarity with the students in Guerrero. His cheek ripped open, leaving a permanent scar.

But Ms Flores has always supported her son, and other young people, in their own struggle for justice.

"You need to confront your country's problems yourselves," she said. "Nobody else will resolve them for you. You need to fight for the life you know you deserve."

- Published20 June 2017

- Published13 March 2018

- Published25 August 2022

- Published29 September 2014