Venezuela crisis: US vows to 'disconnect' Maduro's funding

- Published

Who's really in charge in Venezuela? The BBC's Paul Adams explains

The Trump administration is trying to cut Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro's revenue streams, US National Security Adviser John Bolton says.

The comments come one day after Mr Maduro cut diplomatic ties with the US.

He was angry after they recognised an opposition figure, Juan Guaidó, as interim president on Wednesday.

Mr Bolton told reporters outside the White House the issue was "complicated" but they were working on a plan to funnel funds to Mr Guaidó instead.

Figures from the Trump administration are continuing to try and compound pressure on Mr Maduro as the international community remains divided in its support of him.

Russia has condemned foreign powers for backing Mr Guaidó, saying the move violated international law and was a "direct path to bloodshed".

Mike Pompeo, the US Secretary of State, has now requested a UN Security Council meeting be held on the issue on Saturday.

At a meeting of the Organisation of American States (OAS) on Thursday he described Mr Maduro's government as "morally bankrupt" and "undemocratic to the core".

Are you in Venezuela? Email your story to haveyoursay@bbc.co.uk, external

President Trump has said that "all options are on the table" in response to the unrest.

How did the row develop?

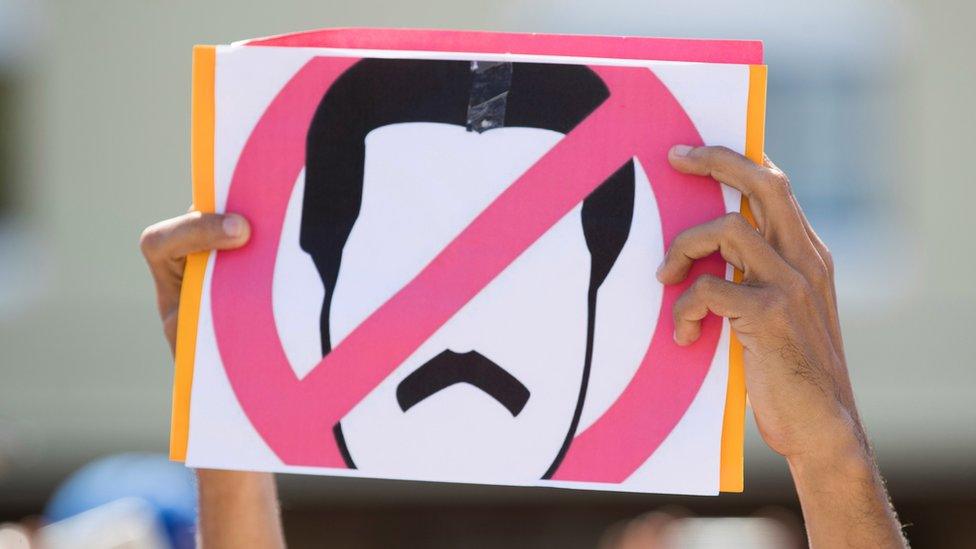

Large protests were organised against, and some in support of, Mr Maduro on Wednesday.

At one demonstration in Caracas, Mr Guaidó, Venezuela's National Assembly leader, declared himself as the country's interim leader.

He said articles within the country's constitution allow him to assume interim power because he believed Mr Maduro's election, and therefore presidency, was invalid.

He has vowed to lead a transitional government and hold free elections.

Within minutes of his declaration, Mr Trump recognised Mr Guaidó as the country's legitimate head of state. A number of South American nations, as well as Canada and the UK, have now followed suit.

The government of Mr Maduro, who has maintained the military's support, described Mr Guaidó's actions as an attempted coup.

Thousands attended a rally in Caracas on Wednesday against President Maduro

Mr Maduro has labelled the US comments a "big provocation" and broken off diplomatic relations.

On Thursday, he ordered the closure of Venezuela's embassy and consulates in the US.

The US state department meanwhile has ordered non-essential staff to leave Venezuela.

Mr Maduro's sovereignty has been backed by China and Russia, who both have strategic interests in his country's economy.

Others, including Mexico and Turkey, have also stood by Mr Maduro.

A Caracas-based NGO, the Observatory of Social Conflict, says that at least 26 people have been killed in demonstrations so far this week.

What could Mr Trump do next?

Analysis by Natalie Sherman, BBC News Business Reporter

The US has already imposed a raft of sanctions in the past two years, which target officials in the Maduro government, restrict Venezuela's access to US debt markets and block dealings with those involved in the country's gold trade.

But so far, the Trump administration has not taken action directly against oil imports, which are a key source of cash.

A stand-off over US embassy personnel could push the White House to take that step.

But analysts cautioned that oil sanctions would likely have limited effect on the Maduro regime, which could redirect shipments to allies such as China and Russia, while blaming the US for any additional hardship.

Meanwhile, the decision would have consequences in the US, which imported almost 20 million barrels of Venezuelan oil, external a month through October of last year.

"At the end of the day, it's a much more symbiotic relationship between Venezuela and the Gulf Coast," said Richard Nephew, a senior research scholar at Columbia University's Center on Global Energy Policy, who worked on sanctions against Iran under the Obama administration.

Mr Nephew said Mr Bolton's comments about supporting the opposition indicate the US may be looking more seriously at preparing an aid package. But he warned: "Getting money back into the opposition's hands is much more complicated."

Why are people protesting?

Mr Maduro has led the country since 2013 and was sworn in for a second term earlier this month. His re-election in May 2018 was marred by an opposition boycott and vote-rigging claims.

The president has faced ongoing criticism international and internal opposition for his human rights record and handling of the economy.

What drives someone to cross South America on foot?

Despite having the world's largest proven oil reserves, Venezuela's economy has been in a state of collapse for several years.

Its industry has suffered mismanagement and oil revenue has dropped significantly.

Endemic hyperinflation and shortages of necessities like food and medicine have hit the population hard and caused millions of Venezuelans to flee.

Strategic partners including China and Russia have invested deeply the country's economy - ploughing billions into trade deals and loans to the help its ailing economy.

Moscow sees Venezuela as one of its closest allies in the region and has sharply rebuked US comments about Mr Guaidó's claim.

Are you in Venezuela? What has life been like in the country? Tell us your story by emailing haveyoursay@bbc.co.uk, external

Please include a contact number if you are willing to speak to a BBC journalist. You can also contact us in the following ways:

WhatsApp: +44 7555 173285

Send pictures/video to yourpics@bbc.co.uk, external

Tweet: @BBC_HaveYourSay, external

Text an SMS or MMS to +44 7624 800 100 (international)

Please read our terms & conditions and privacy policy

- Published24 January 2019

- Published23 January 2020

- Published12 August 2021

- Published30 December 2018

- Published10 August 2017