Brazil dam disaster: Inside the village destroyed by surging sludge

- Published

Many residents are still missing almost a week after the tragedy

Last Friday, Sirley Gonçalves was cleaning up the house she and her husband had just finished building in this rural village in south-eastern Brazil when she heard a huge noise.

Her instinct was to run. A dam at the mine where many in Córrego do Feijão made a living had burst, sending big waves of waste from iron ore extraction, destroying everything here.

Hours earlier, Claudio Pereira Silva, her 44-year-old husband, had gone to work at the mine, where for five years he had been a train operator. "My husband left home for work in the morning, said 'God be with you', as he always did," said 54-year-old Ms Gonçalves, her tears coming easily.

But he never came back.

The dam collapsed at around lunchtime without warning. The torrent of toxic sludge buried not only parts of her village but the plant's own facilities, including the cafeteria where hundreds of workers were believed to be eating, the administrative buildings and the loading terminal for trains, where Mr Silva worked.

Sirley Gonçalves' husband was working at the mining complex when the dam collapsed

"He really liked his work," said Ms Gonçalves, "but he was afraid that something could happen one day. We were always at meetings about safety and evacuation routes."

But the alarm system that Vale, Brazil's largest mining company and the mine's owner, had installed in the village to warn the residents of any risk did not go off. Those who survived ran for their lives after hearing the noise that terrified Ms Gonçalves.

Her home was unaffected. But Córrego do Feijão, a district of Brumadinho where the dam was located, was the worst-hit area. Its lower part now lies under a thick layer of mud, in some places up to 15m (49ft). And many of Ms Gonçalves' neighbours are believed to be under it.

"It's so difficult," she said. "We loved each other so much."

The trail of destruction spreads over an area equivalent to more than 100 football pitches, according to Ibama, Brazil's environment agency, and it reaches the vital Paraopeba river.

Almost a week later, there is almost no hope that any of the 259 people who are still missing will be found alive. Ms Gonçalves believes her husband's body is inside one of the locomotives, where one of his colleagues has been found, but access to the area is difficult. Ninety-nine deaths have already been confirmed.

It is not known what caused the dam to collapse, as Vale says it was being regularly monitored and had stability reports issued by independent companies. But five people connected with the company's licensing process have been arrested.

Admiration turns into anger

Vale is the biggest employer in Brumadinho and mining royalties make it the town's biggest source of revenue. A recent ranking by Valor newspaper considered it the fifth best company in which to work in Brazil.

Now the name sparks outrage with many in Córrego do Feijão and across Brazil who blame the company for this tragedy.

"After this tragedy, this place is over for us," Ms Gonçalves said

"The families are desperate. Vale destroyed our lives," said Ms Gonçalves. "They must have known the dam would break. But they don't care about their employees, they care about their money."

This comes with added disbelief at seeing history repeat itself. "Vale, reoffending assassin," says a fresh graffiti on a wall in the village.

In November 2015, a mining dam operated by Vale's subsidiary, Samarco, collapsed in the town of Mariana, just 120km (74 miles) away in the same state of Minas Gerais, killing 19 people and devastating two nearby villages.

The trail of destruction along the Doce river became Brazil's worst environmental disaster and, up until today, no-one has been convicted in the case while residents say they are still waiting compensation.

The village was hit by a sea of muddy sludge without warning

Many in Córrego do Feijão worked at the nearby mining complex

It was also an eye-opener in Brumadinho and other towns in Minas Gerais which are next to mines, an important regional industry. The state has more than 200 dams classified with "high potential risk" in case of a collapse.

"After Mariana, we came to fear that the same could happen here," said Caio Cesar de Assis Braga, a city legislator in Brumadinho.

After visiting the Córrego do Feijão mine last December, he demanded assurances from Vale on safety concerns. But he never got an answer.

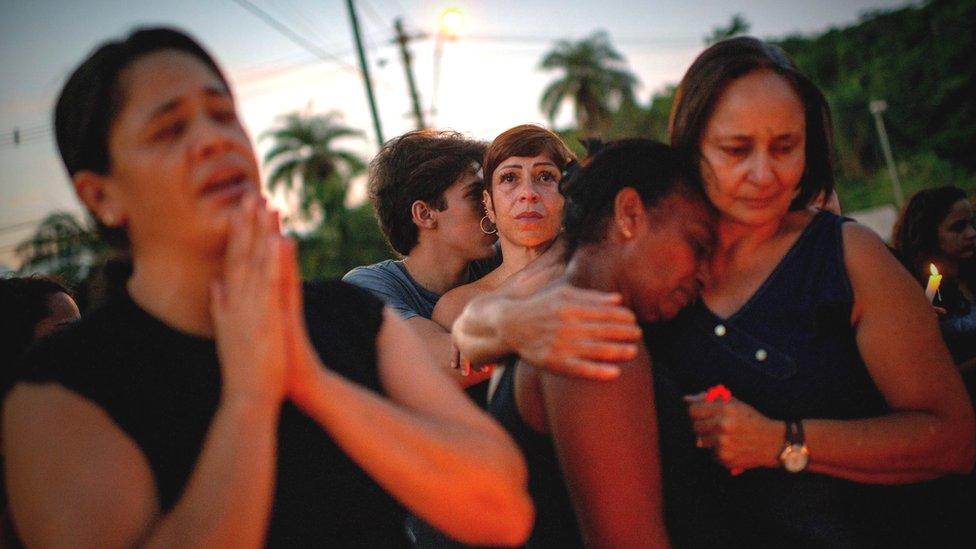

"Our feeling now is of outrage because it's too much sadness," he said at the funeral of a friend who did not manage to escape the mud. "The city lost its joy, its people. Brumadinho is dead."

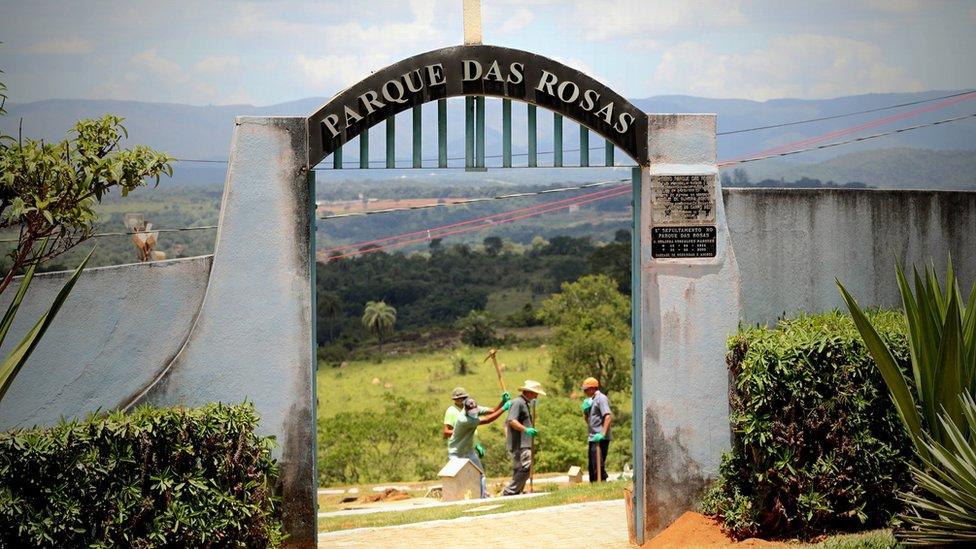

The first bodies recovered from the mud were buried in Brumadinho

He counted 25 people he knew as missing. "Soon people will be coming here to make documentaries about how we've been forgotten, about how nothing has been done."

For now, Ms Gonçalves and many other women are in an agonising wait. With her partner for 20 years presumed dead, she thinks she will never be able to live in their new house.

"After this tragedy, this place is over for us."

- Published30 January 2019

- Published26 January 2019