After the fight for humanitarian aid, what next for Venezuela’s opposition?

- Published

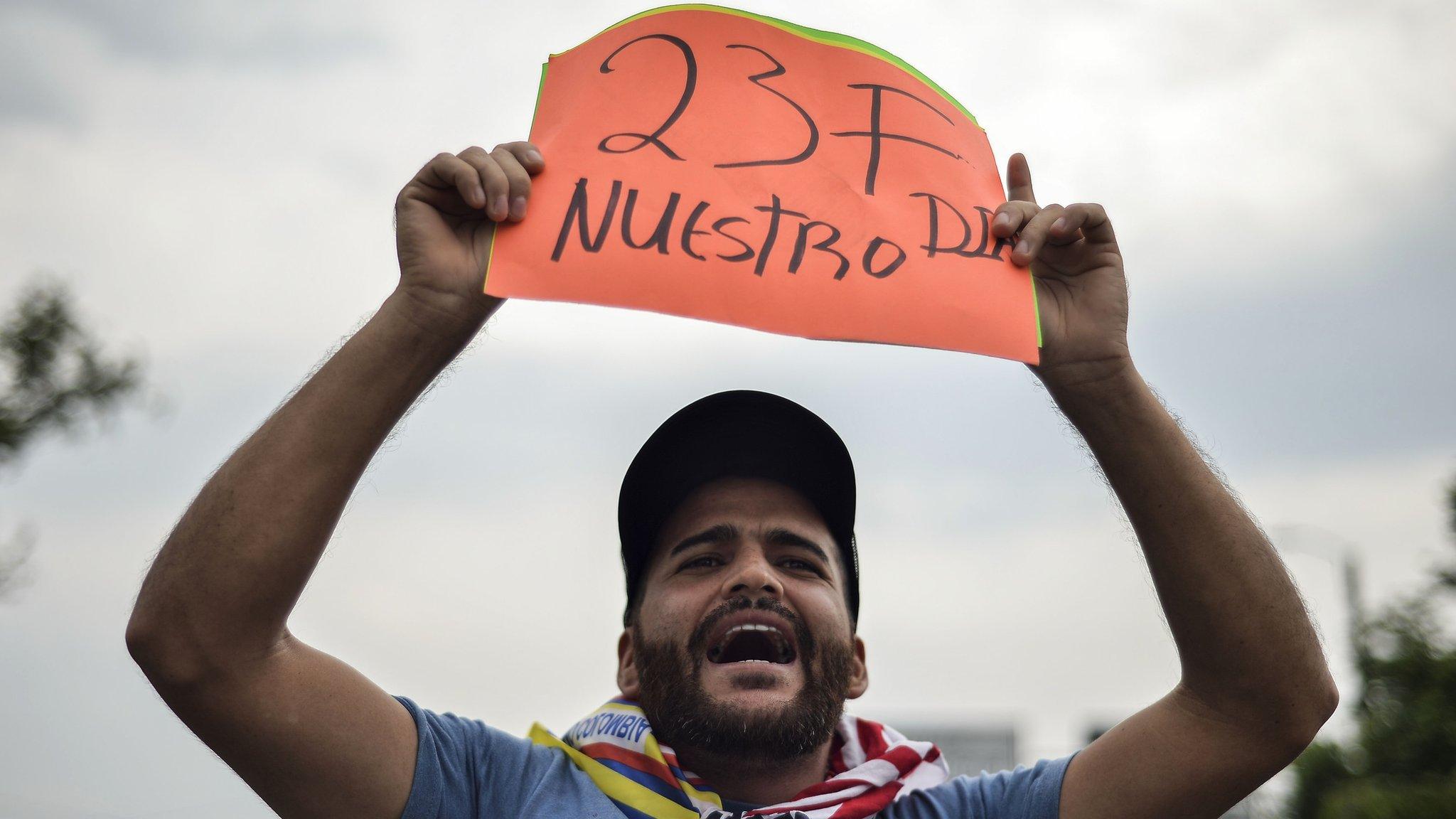

Deadly border clashes have taken place after President Nicolás Maduro blocked humanitarian aid from crossing from Colombia and Brazil

After a weekend of violence, it is time for reflection. And Plan B.

Opposition leader Juan Guaidó will be meeting regional members of the Lima Group in Colombia's capital, Bogotá, on Monday.

US Vice-President Mike Pence is also taking part to discuss the crisis in Venezuela. The Trump administration has been a big backer of Mr Guaidó since he declared himself interim president last month.

Juan Guaidó has said that after Saturday's events, he has decided to formally ask the international community to keep all options on the table.

US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo tweeted over the weekend that America would "take action against those who oppose the peaceful restoration of democracy in Venezuela".

Read between the lines, and military intervention, something that US President Donald Trump said he would not rule out, is clearly being left as a form of "action".

Families divided

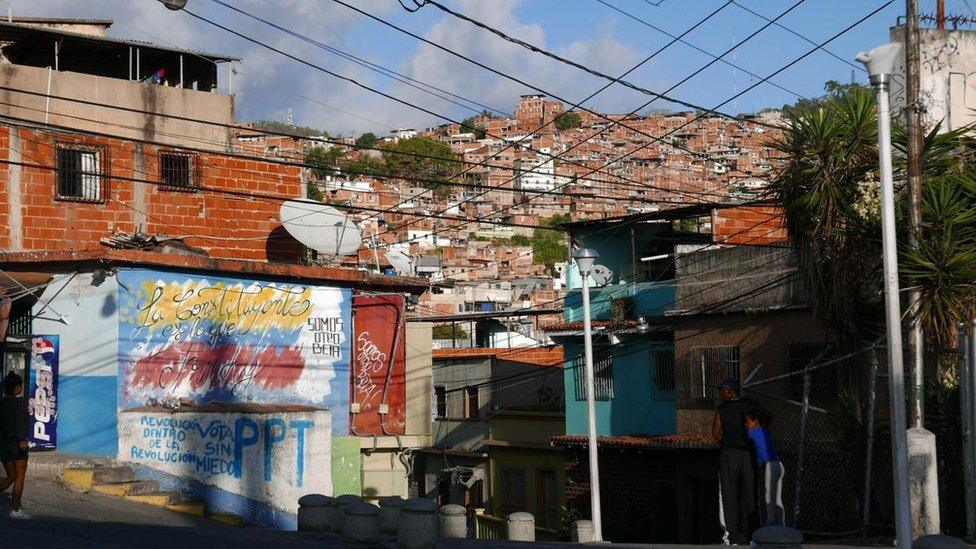

Keddy Moreno lives in Venezuela's biggest slum, Petare, a neighbourhood of the capital, Caracas. She is prepared for military intervention - anything to end the hardships she faces on a daily basis.

I meet her just before she heads to Sunday evening Mass. The priest's sermon touches upon the need for forgiveness in Venezuela - and the need to end the political fight so families are no longer divided.

Keddy Moreno says efforts at the weekend to block the aid coming in were "a great injustice"

That is a story Keddy knows all too well. Her daughter left Venezuela to look for work in Peru two years ago, just four months after giving birth. Keddy's now bringing up her little granddaughter alone.

"This weekend was a great injustice," she says of the government's efforts to block the aid coming in. "But it could have been worse. It gives us more encouragement that things can change."

Petare, where Keddy lives, is Venezuela's largest slum

Keddy thinks Juan Guaidó is the best man to take Venezuela forward.

"If only he had appeared before, things could have changed sooner."

Intervention - more harm than good?

Not far from Petare, in one of Caracas' wealthier suburbs, families are making the most of the sunny weekend on the Cota Mil ringroad which snakes along the north of the capital, under the iconic Avila mountain that overlooks the metropolis.

Petroleum engineer Renni Pavolini is out walking his seven-month-old spaniel Eva. He thinks the US needs to get involved in bringing the presidency of President Maduro to an end, despite fears from many that it could do more harm than good.

Renni Pavolini says he supports foreign intervention if it will "make a big change for this country"

"They are always being interventionist," he says, giving the past examples of Vietnam, Iraq and Cuba. "But if that intervention will make a big change for this country, I think it's a good thing."

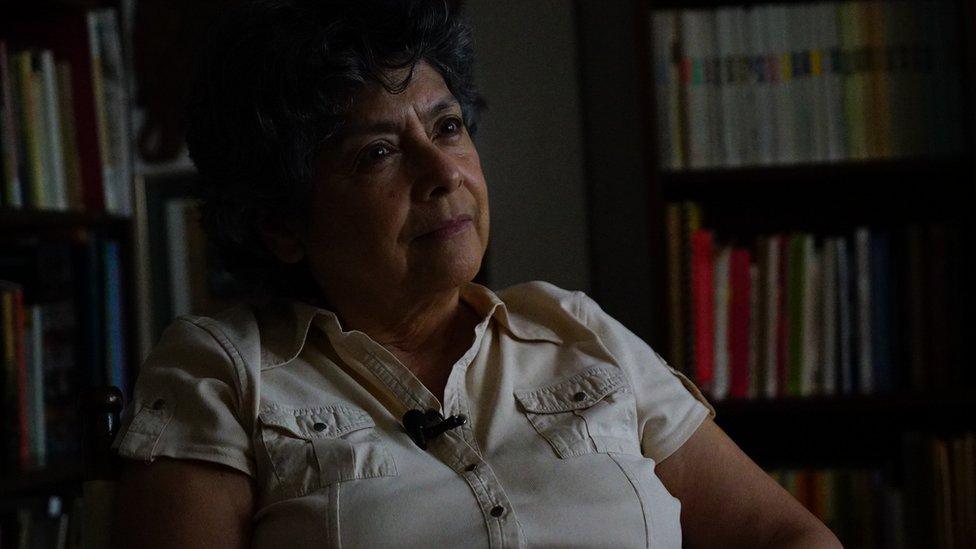

Good or bad, there are not many options left, according to Margarita Lopez Maya, a professor at the Central University of Caracas.

Margarita Lopez Maya, a professor at the Central University of Caracas, says a peaceful solution to current hostilities is "very difficult"

"Venezuelans keep on betting on the possibility of a peaceful way out of this, but the nature of the Maduro government makes it very difficult for a peaceful way out," she says.

"We have seen that they don't care about the Venezuelan people. They don't care about the cruelty or repression. They don't have scruples. If they have to kill people, they will kill them. If they have to starve them, they will starve them."

Fears of intervention

But people on both sides of the political argument fear military intervention.

"I think it would devastate an already dilapidated infrastructure, it would create divisions within the international community, it would raise questions about the legitimacy of the new Venezuelan authorities, it would set an awful precedent for the region," says Benjamin Gedan of the Wilson Centre in Washington and former South America director on the National Security Council.

"It carries great risks and it's not necessary."

Maduro: US "warmongering" in order to take over Venezuela

Mr Gedan instead urges patience. The most recent sanctions placed on the state-oil company PDVSA will take effect in the coming weeks and that, he says, will pile more pressure on the government.

"Does he still have the rents to distribute to the elites?" he asks. "It's not ideological loyalty any more, it's shared impunity and it's bribery."

Once that money disappears, so too will the loyalty.

Concerts for peace

Mr Maduro is not giving up yet. In the centre of Caracas this weekend, the government put on a concert in the name of peace, hiring artists to belt out the political message that it does not need other countries to get involved and fix Venezuela.

President Maduro spoke at a pro-government concert this weekend in light of another, anti-Maduro concert organised by opposition groups and British billionaire Richard Branson

"What we want is for the whole world to call on Donald Trump, to call on the US, to call on the countries that want Venezuela choked, and remind them that we are a free country," says Ezequiel Suarez who is in the crowd. "We can decide ourselves what kind of future we deserve and we want to construct."

On a nearby building, there is a giant poster with the face of Nicolás Maduro overlooking the concert. The future belongs to us, it reads - but for how long?

- Published25 February 2019

- Published24 February 2019

- Published23 February 2019

- Published22 February 2019