Haiti: The university planning a green revolution

- Published

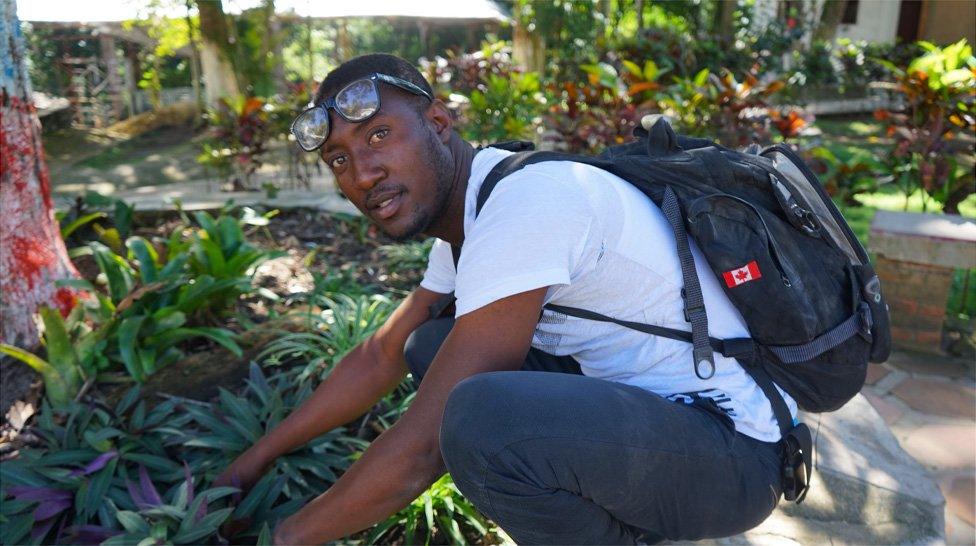

Belotte Walky dreams of becoming a farmer to feed fellow Haitians

As far as dreams go, it is a fairly modest one. It is neither fame nor riches that student Belotte Walky aspires to; just a farm to help feed his compatriots, with jobs to keep them employed.

This he divulges sitting under a 250-year-old ficus, one of many age-old trees shading the North Haiti Christian University (UCNH) in Haut-Limbé.

Like Belotte, the vast majority of students are here to read agronomy to forge a career in farming and, ultimately, play a part in overturning Haiti's economic fortunes.

But this university found at the end of a bone-shaking road an hour from Cap-Haitien is renowned for more than just its academic offerings.

Wildlife haven

In a country where deforestation earns as many superlatives as poverty, UCNH's ancient flora across its 19-acre campus has become a haven for rare, endemic birds thanks to a generations-long ban on tree felling.

Not only can students learn all about sustainable agricultural practices, they can experience the symbiosis that occurs when the Earth is left to its own devices.

"Mass extinction" is already under way, the findings by US and Haitian researchers warned.

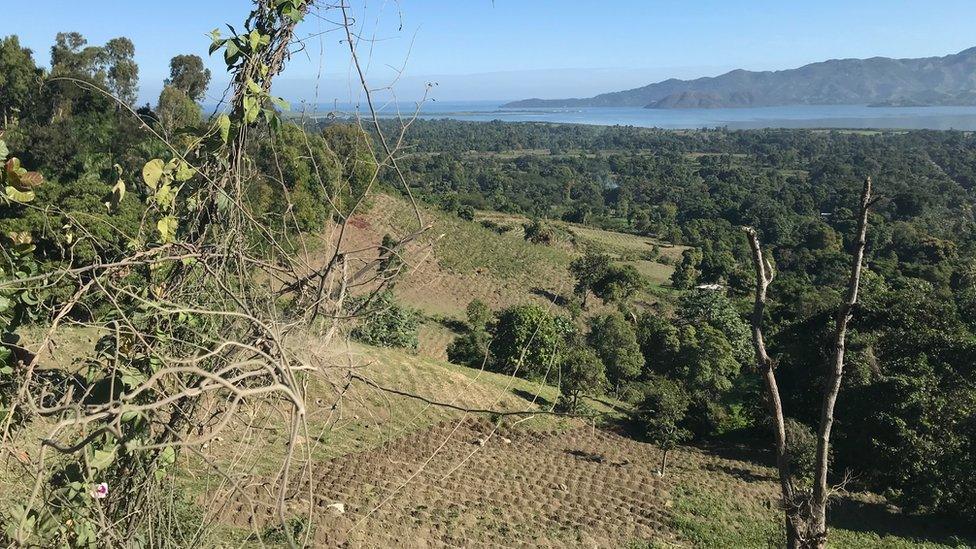

Swathes of Haiti's virgin forests were destroyed by French colonists in the 17th and 18th Centuries to make way for sugarcane plantations. More recent losses are due to small-scale agriculture and the production of charcoal, widely used as cheap fuel.

Without tree roots to hold soil, Haiti's mountainsides are especially vulnerable to landslides and flooding.

"I always tell people, plant trees; the more we have, the better the weather," Belotte says. "Some find that difficult to understand. Many charcoal sellers ask, what will I give my family to eat? I try to show them trees are good for food."

Hunger, in Belotte's home village of Pignon, is never far away.

"Many people in rural areas don't have jobs. I see a lot of people suffering in my community. I cry when I see where some have to sleep," he says. "Since I was a child I wanted to become a farmer so I could help them."

When an owl is not just an owl

Balancing ingrained cultural beliefs with ecological education goes to the heart of Haiti's unique and complex relationship with the environment.

"You show students a picture of an owl and they cover their eyes," explains ecology professor Debbie Baker.

In the Haitian voodoo religion, the owl is associated with Marinette, a spirit symbolising power and violence.

"It's hard to address spiritual issues, so I tell the class, owls are very important because they come out at night and kill rats," Debbie, who studied in her native US, continues. "And any time I teach about snakes it's a very highly charged lesson as the snake is highly significant in voodoo."

The serpent god, Damballa, is one of the most important deities, believed by some to be the creator of the world.

"People rely on the environment for everything from clean water to food so I work these beliefs into my teaching," Debbie says.

"I tell students about the vital roles different creatures play, like the hummingbirds that pollinate plants, and about woodpeckers who control the insect population and make holes for other birds to live in which helps the ecosystem," Debbie adds.

Fostering hope

Since taking up the position in November, she has identified 30 different species of birds on campus, including threatened Hispaniolan parakeets, and 60 in the surrounding area.

Among the bird species Debbie has spotted on campus are the Hispaniolan parakeet

...and the red-tailed hawk

as well as the black-crowned Palm-Tanager

Seeing young people passionate about their studies amid Haiti's current political tension, which sparked a wave of violent protests in the capital Port-au-Prince, is heartening for Laurel Casseus whose father started the school as a seminary in 1947.

"It's a very difficult time in Haiti and many people are discouraged," she tells the BBC. "Seeing our students so committed to helping future generations makes you realise, however bad things are, there's still hope."

This year will mark the university's 25th anniversary. It evolved into its current form during upheaval in the 1990s after the military overthrew then-President Jean-Bertrand Aristide.

"The UN trade embargo was on and there was a need to feed [people]," recalls Laurel's husband, and former university president, Jules Casseus. "That's when we added agriculture to the curriculum. These days we have more than 200 graduates per class."

Laurel Casseus's father founded the university and her husband, Jules, is its former president

UCNH's innovative work is now being rolled out further still. A major reforestation initiative seeks to plant 1.5 million trees, including coffee and cacao, by 2024.

Guy Buckmaster, who heads the programme, has already signed up almost 4,000 farmers to plant them, in conjunction with local fair trade organisations.

The World Food Programme estimates Haiti imports more than half the food it needs to feed its population.

Guy hopes the project will help address that. "The volume of imports keeps Haiti reliant on other countries," he says. "We have to turn things around."