Venezuela crisis: The political battle and the people caught in the middle

- Published

Violence has once again broken out on the streets of Venezuela. But just what has happened to the country, politically and economically, to cause such anger and division?

The sun hadn't yet risen but Venezuelans were wide awake. A little before 6am, Juan Guaidó went live via social media from outside La Carlota military base in Caracas to call the country to action.

"The moment is now," said the opposition leader, flanked by members of the security forces and his political mentor, Leopoldo López, who had evidently escaped from house arrest. "I invite you to come out on to the streets. The first of May begins now," referring to a large anti-government demonstration planned for the following day.

It was a risky move. If this was indeed the "final phase" of his effort to oust President Maduro, Mr Guaidó would need more than the handful of troops around him. He'd need the entire country to react. And historically in Venezuela, such moments tend to result in bloodshed.

In the end, it was neither one thing nor the other.

The uprising didn't unseat Mr Maduro or necessarily weaken his grip on power. Thankfully, there wasn't the degree of deadly violence that many had expected at the start of the day - notwithstanding dozens injured by pellets and rubber bullets and the shocking images of protesters outside La Carlota being run over by an armoured car.

Leopoldo López ended the day inside the Spanish Embassy in Caracas and Juan Guaidó insisted the uprising had not been a coup attempt but an act of "peaceful rebellion".

Venezuela crisis: The four countries interested in the presidential battle

Whatever Mr Guaidó hoped the day would bring clearly didn't happen. Yet it was another sign that President Maduro can still expect moments of resistance and conflict from an opposition determined to see the back of him and a population exhausted with a collapsing economy and a lack of basic services.

Amid the political brinksmanship, I was reminded of that collective exhaustion at the status quo, specifically of a few precious hours, a few weeks before the latest crisis, when running water returned to a handful of homes in La Vega.

As the news spread around the sprawling shantytown in western Caracas, residents made their way down from distant corners to the fortunate few brick shacks - plastic bottles and buckets in hand - to fill up before it was shut off again.

One neighbour, Ramelia Silva, struggling to carry her load as she corralled her grandchildren up the steep hillsides, showed me water which was yellowish and smelled foul.

"It's not fit for human consumption," Ramelia acknowledged. "We should only use it for washing and in the bathroom." However, in the middle of a water crisis, she said that just wasn't realistic.

"How long will it go on?" she asked angrily. "We can't keep living like this."

La Vega has been without a dependable water supply for over a year, explains community leader, Jairo Perez.

Venezuelan opposition leader Juan Guaidó called for people to come out on the streets against the Maduro government

"I have warned the government, I've sent reports to NGOs that we work with and I keep repeating: an epidemic is on its way. We're on the verge of a secondary public health epidemic because this water should not be consumed.

A couple of days later, I put Ramelia's basic point to Mr Guaidó between parliamentary sessions at the National Assembly: how long before anything changes in Venezuela?

"I hope very soon," was his reply, denying the opposition had either miscalculated or squandered its momentum.

Beyond his enigmatic remark, though, there was little sign of the dramatic twist to come. At that point, the idea of him commanding rebel troops in clashes with their loyalist counterparts seemed unlikely. But Venezuela, especially at present, specialises in the unexpected.

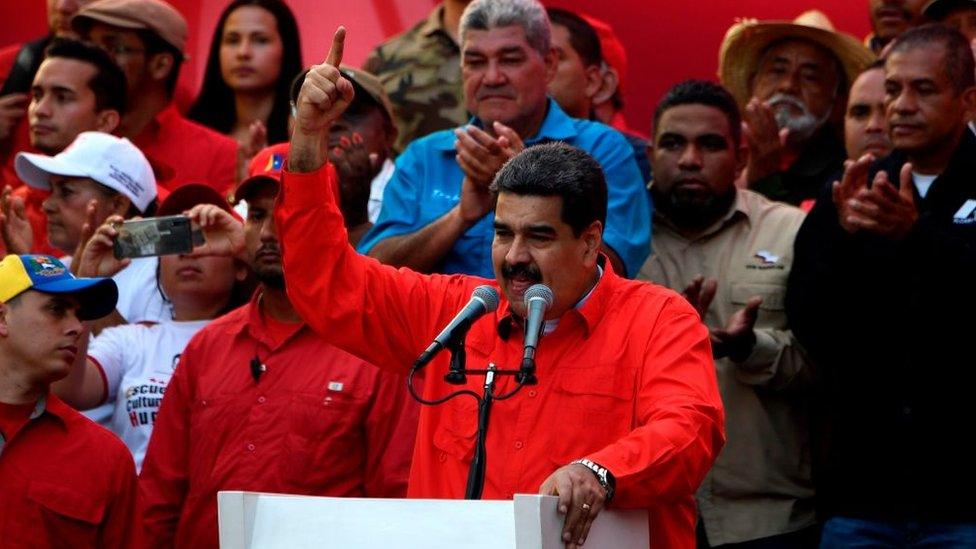

Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro denied US claims that he had been ready to leave the country

After declaring himself president in January, Guaidó was immediately recognised by the United States and more than 50 other nations.

Washington extended its sanctions from the Maduro inner circle to the all-important energy industry. By early March, people in Guaidó's team spoke confidently of being close to victory, of having passed the halfway point in a three- or four-month process to reach the presidential palace, Miraflores.

"He'll be gone any day now," was their prevailing sentiment.

By mid-April, those same advisers had radically revised that view. They spoke instead in more conservative terms of "something" happening "before the end of the year".

It's still not clear if this latest uprising was the sum total of that "something" or if there is more to come. Given the story so far, most Venezuelans expect further drama ahead.

Soraya is one of those washing clothes in dirty water also used for cooking and drinking

In essence, Guaidó has two options to taking power: via the streets or the military.

Or some kind of simultaneous combination of the two, the elusive "civic-military pact" which Maduro's predecessor and mentor, Hugo Chávez, so prided himself on.

At Guaidó rallies, his supporters still turn out and make their anti-Maduro feelings heard despite the passing of the weeks and months. But it's becoming increasingly tough for people to keep taking to the streets when they have so much else to deal with, as thousands of communities like La Vega struggle to overcome the challenges of daily life in Venezuela.

Then there are the threats and intimidation from radical pro-government motorbike gangs called "colectivos" - in essence, armed paramilitary groups - and many are understandably too frightened to risk participating in demonstrations. After scores of young demonstrators and some police officers were killed in clashes in 2014 and 2017, there's limited appetite for more pitched battles.

"I'm not going," Carmela tells me at a kids' football match a few hours before another protest. She lives in La Candelaria, a part of the capital where "everything is controlled by the colectivos: the supermarkets, the streets, everything."

"I'm too scared of them to protest," Carmela explains, unwilling to give her full name. "They're capable of killing people who take part. I have a six-year-old boy and can't risk leaving him with no mother."

Beyond street protests the other main actor in the Venezuelan conflict is the military.

This wasn't the first time Guaidó made a direct plea to the Venezuelan military to switch sides.

At the height of the tension in late February, with a convoy of humanitarian aid poised at the border with Colombia, a few hundred soldiers did jump ship in a number of much-publicised defections.

What role might the military play in a resolution of the crisis?

Yet the vast majority of rank-and-file troops stayed loyal, as did the top brass. That happened again on this latest occasion and both times, it has undoubtedly been a disappointment to the opposition.

Furthermore, if recent Venezuelan history has taught anything, it's that the military is key to owning the keys to Miraflores. Without them, taking power is virtually impossible.

So, if things reach a breaking point in Venezuela, always a difficult thing to measure, where would the military's ultimate loyalty lie? With Maduro personally, with the "Bolivarian Revolution" begun by Hugo Chávez or with the people calling for change?

"With Benjamin Franklin," quips economist and opposition deputy, Angel Alvarado, referring to the US founding father whose face appears on the $100 bill.

"The army doesn't have any ideology. There are some soldiers whose heart is to the left or the right, of course. But I think on the whole the army just wants to maximise their profits."

In Venezuela, the military has control of many key sectors of the economy.

"Food production, mining, the oil sector, agriculture, anywhere there is money and rents to be made, you will find the military," claims Alvarado. Maintaining that monopoly is paramount to them, he argues.

"The problem is not hyperinflation and it's not the humanitarian emergency," argues Alvarado. "It's the collapse of the economy which started in 2007."

He accuses Hugo Chávez of having indebted the country by billions of dollars which was only covered by a high oil price.

Once that price began to drop in 2009, and a policy of nationalisation and expropriation damaged crucial sectors like agriculture, the dependence on oil-exports worsened. Today, with far fewer dollars available for imports, the economic situation is unsustainable.

"I think we are in a tipping point right now," he says, and that after the electricity outage, oil production has dropped to about 500,000 barrels per day.

With fewer countries to export Venezuela's oil to, Alvarado adds: "I think Maduro is out of money."

At a bar popular with Maduro loyalists in the town of Charallave, employees and union representatives of the state-owned cement company are sat at plastic tables drinking cold beer after work. The bar is one of the few with lights on, running off a generator during one of the town's scheduled power cuts.

The workers don't hold President Maduro responsible for the chaos, sticking to the party-line about sabotage of the electrical grid and co-ordinated attacks by Washington and Juan Guaidó.

Maduro supporters in this bar believe that Washington is behind the crisis

"We're being punished because we're not a servile government to US interests," said one member of the group. "If a change comes it must be for better, not for worse. Not to allow the opposition to take everything we've built over the years," echoed another, amid clapping and shouts of "Viva Maduro!".

Political loyalties aside, they're right to identify the clear international dimension to the situation in Venezuela.

Washington has repeatedly said that "all options are on the table" when it comes to Venezuela, including the military one. Barring the most radical, few welcome the idea of foreign troops on Venezuelan soil.

The US is putting the squeeze on three main socialist allies: Venezuela, Nicaragua and Cuba. "The Troika of Tyranny" as National Security Advisor, John Bolton, has dubbed them.

President Donald Trump has accused Cuba of placing troops into Venezuela, something robustly denied by Havana. Whatever happens next, Venezuela and Cuba know to expect nothing but hostility while Mr Trump is in the White House.

In April, Venezuela's foreign minister, Jorge Arreaza, called a news conference after a trip to several nations sympathetic to the Maduro government, including Turkey and Syria, where he heard from Bashar al-Assad about his experience of "resistance".

And, in a very deliberate message to Washington, Mr Arreaza underlined that Venezuela "will continue military-technical cooperation with Russia".

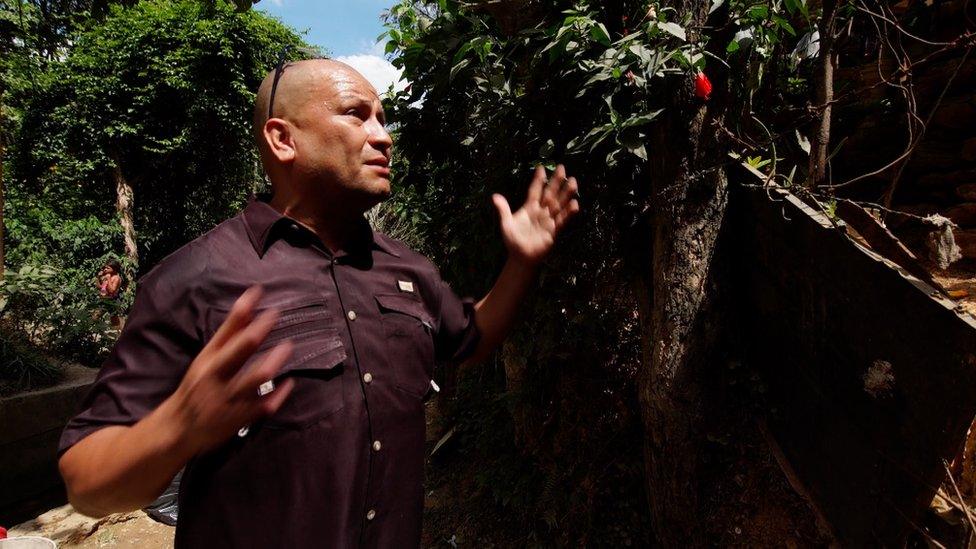

La Vega community leader Jairo Perez says Venezuela is like a country at war

With Russia vocally backing President Maduro at every turn, Venezuela is being drawn into a battle between the superpowers, a proxy conflict more reminiscent of the 1980s than 2019.

Before leaving La Vega, community leader Jairo Perez, took me to a vantage point high above the shantytown, pointing out each of the smaller neighbourhoods below by name.

He knows this poor district of Caracas intimately. It's where he grew up, where his family is and, as far as he's concerned, where he'll die.

Yet even long-standing residents like Jairo have never seen it like this. The shortages and dire needs of his community remind him of images he's only seen on television about post-conflict nations.

"We're like a country at war but there's no war," he reflects.

Not, at least, a conventional one.

- Published1 May 2019

- Published9 September 2024