The elite soldiers protecting the Amazon rainforest

- Published

Sergeant Vadim, 31, leads a recce of the forest looking for illegal gold miners

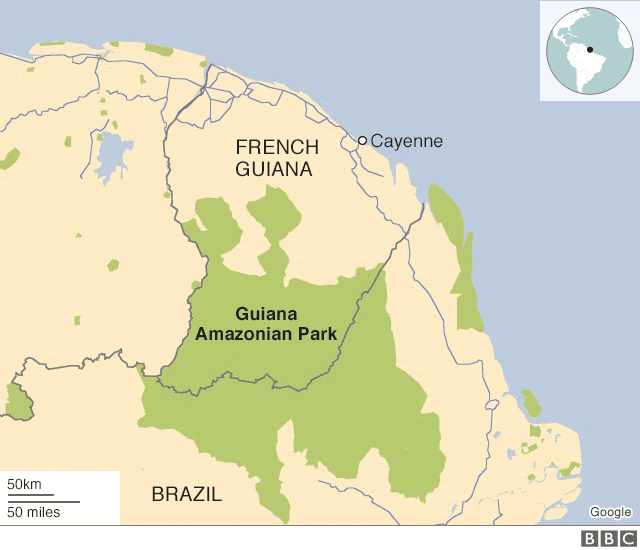

French Guiana, a small French overseas territory on the north-eastern coast of South America, is one of the most forested nations on the planet, but its precious ecosystem is under threat from illegal gold mining.

Sergeant Vadim raises his left hand bringing his squad to a halt. His right hand remains firmly clasped around his rifle.

"Here you can see clearly the path of gold miners," he says, whilst pointing towards a faint track covered in leaves. "They were here three or four days ago carrying heavy goods."

Sgt Vadim is part of the French Foreign Legion - an elite infantry unit of the French army made up of mostly international recruits tasked with patrolling the dense rainforest.

After further surveying the jungle, Sgt Vadim gives a short sharp whistle. Seconds later, a reply emanates from somewhere deep in the undergrowth. A second unit of men is close by.

More than 90% of the country is forested

Manoeuvring in a pincer movement, the two units hope to flush out anyone attempting to plunder the forest for its riches. "Every country must defend its borders and stop illegal trafficking," says Capt Vianney, head of the operation and Sgt Vadim's commanding officer.

"But here in French Guiana we have a unique treasure, the jungle. Our mission is to protect it."

Beneath the Amazon rainforest lies treasure: gold deposits can be found just 15m (50ft) below the forest floor.

For centuries, prospectors have been lured into these forests in the hope of finding a fortune. But just over a decade ago, when the economic crash of 2008 caused the price of gold to skyrocket, a gold rush began all over the Amazon jungle.

Since then, the price of gold has continued to soar and rampant illegal gold mining has destroyed swathes of jungle from Ecuador across Peru, Colombia and Venezuela to Brazil.

In French Guiana, which has a population of less than 300,000 people, there are an estimated 8,000 to 10,000 illegal miners.

Large illegal mining sites such as this one close to the Maroni river have been found across French Guiana

In the jungle there are no roads, only rivers. French forces manoeuvre around the forest either on foot or by gasoline-powered boats

As Dominick Plouvier, conservation expert and director of Amazon Conservation Team, external explains, the problem lies in the use of one high volatile chemical.

"Mercury, used in the extraction process is the big problem. It pollutes the rivers, which then poisons the fish, which then in turn poisons the people who eat the fish."

Mercury is a highly toxic and indestructible substance which is poisonous to humans.

After excavating large amounts of earth, prospectors add mercury to separate out the tiny flecks of gold from the soil. Within minutes it binds with the gold, allowing miners to simply wash away the dirt. The mercury can then be simply burnt off leaving the gold behind.

Mercury is used to separate the gold from the soil

For every gram of gold extracted, at least one gram of mercury is also required. Left to wash away, discarded mercury enters the huge Amazon river network. Accumulating in fish, it then enters the food chain.

"Mercury acts very quickly," explains Mr Plouvier. "Attacking the nervous system, it damages your lungs, your kidneys and your brain. We have seen its effects on local children brought into hospital."

Scientists estimate one third of all the mercury produced by human activity on the planet comes from small-scale gold mining.

Legionnaires keep a look-out on the river separating French Guiana from Brazil

On the French Guiana-Brazil border, gold mining is mainly carried out by "garimpeiros", the Portuguese word used to described small-scale miners who extract the metal illegally.

"Most of the time, the garimpeiros are poor lads from Brazil looking for easy money. They live in the forest for months and months," says Capt Vianney.

"Back home they would earn 800 reais a month ($200; £150) for doing small labouring jobs. But in the forest, they can earn that in a few days."

It is the French Foreign Legion's job to find the garimpeiros and to destroy their camps.

Capt Vianney coordinates the operation from within the jungle via a satellite phone

Sgt Vadim signals to his team to move off. They tread carefully, scouring the forest for clues.

With no mobile phone signal due to the thick forest canopy, the garimpeiros leave messages for each other hidden in the forest. Elusive machete marks in the trunk of a tree, or hidden amongst the undergrowth, the red arrow on Marlboro cigarette packets are placed so as to point the way to their hidden camps.

Operating here requires perseverance as it much as it does a machete. Lying in wait, in this inhospitable labyrinth is a menagerie of poisonous insects, frogs, spiders and snakes. Mosquitoes carry malaria, dengue, yellow fever as well as zika, while in the rivers, caiman compete for space with piranhas.

"In the river there is also an electric eel with enough volts to kill a horse," says Sgt Vadim with a wry smile.

The legionnaires stop and search local people in the hope of catching gold smugglers

Covering up to 40km (25 miles) a day, the infantry may follow a single track for weeks in the hope of finding a hidden site. During these missions, they are dependent on a helicopter to deliver food and fresh water every few days. In the evenings, after a wash in the river, they spend the night in hammocks before rising early again the next day.

But despite all their armoury, helicopter support, gasoline boats, and GPS tracking systems, they rarely catch anyone. Often by the time they arrive, the gold diggers have already been tipped off and fled.

The legionnaires often sleep in the forest

"We are watched all day long," says Capt Vianney. "They know about us before we even land".

Operating across an area the size of Ireland, this regiment of 400 men simply cannot be everywhere at once. But for conservation expert Dominick Plouvier, both the garimpeiros and the army acting on behalf of the French government are chasing short-term solutions.

"As soon as the army leaves, the garimpeiros return," he explains. "Gold mining is such an important livelihood in this area, you can't just say 'don't do it'."

"Many local people as well as Brazilians depend on this economy. If you want to stop the destruction of the forest, you need to offer legal and sustainable alternatives".

- Published2 June 2023

- Published25 April 2019

- Published25 April 2019