Venezuela crisis: What happened to uprising against Maduro?

- Published

What are the real reasons behind Venezuela’s blackouts?

I have it on good authority that the plot to unseat Venezuela's President Nicolás Maduro started with members of his inner circle, not with the opposition.

The big question is why they backed out, although this Washington Post article weaves quite a convincing tale of the intrigue., external

What is clear is that it was a sophisticated scheme, the like of which we most probably will not see again soon.

Discontent at the top did expose fractures in the Maduro government, suggesting the president has been weakened by internal tensions. But one month on, neither he nor the opposition headed by National Assembly Speaker Juan Guaidó seems capable of vanquishing the other in a bold definitive move.

Instead they have begun wary talks in a new peace process in Oslo mediated by the Norwegians.

In the meantime, Venezuelans who thought the attempted uprising might stem the tide of their misery have gone back to the business of surviving.

Quite literally so for one young woman with whom I stopped to chat near the centre of Caracas.

She told me she had been in hospital for two months awaiting surgery for her cracked vertebrae. But it did not happen in the end because the doctors ran out of supplies, including disinfectants.

Out of 10 women who did have surgeries during her time there, she said, nine went home with a bacterial infection contracted in the operating theatre, including one who was paralysed by meningitis.

Such horror stories are endemic in this oil-rich nation now in the grip of a profound economic crisis, brought on by years of government mismanagement and corruption and compounded by low oil prices.

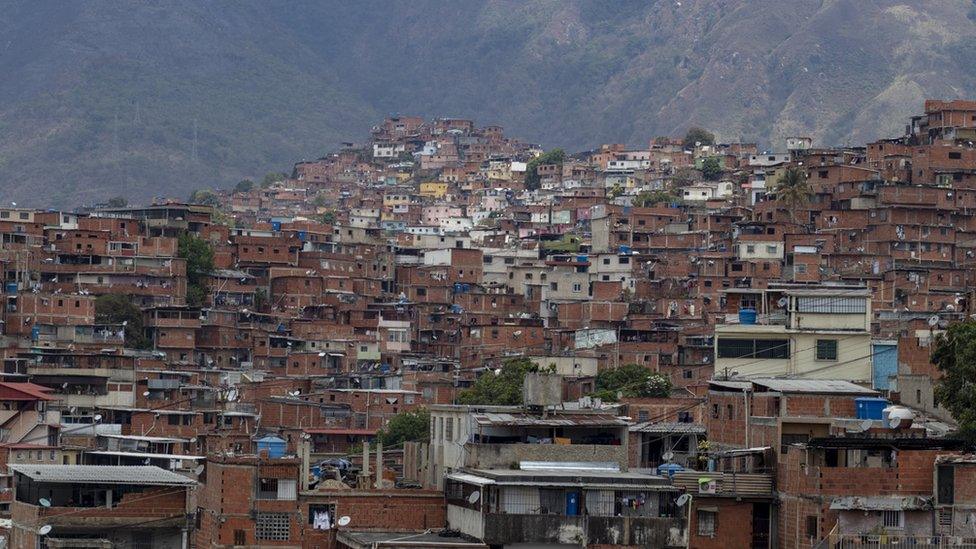

Thousands of people live in Petare, Venezuela's largest slum

The most vulnerable, of course, are the children. Maria Gutierrez is on the frontlines of a battle against malnutrition in the slum of Petare, Venezuela's largest.

She makes sure that the neediest children in her neighbourhood eat once a day, serving up a carefully composed meal of rice, vegetables and meat, cooked in her small kitchen and paid for by an opposition organization.

"Look," she told me, pulling forward two boys: "Look how short they are." Her son, the same age, was twice as tall.

Even in Venezuela's slums people used to have enough to eat because they got food subsidized by the socialist government. They still get some of that, but much less as the economic crisis deepens.

And it will almost certainly get worse with crippling US sanctions. That is the main strategy by which the Trump administration aims to force Mr Maduro out of office and help Mr Guaidó replace him with a transitional government that organizes new presidential elections.

Why Venezuela matters to the US... and vice versa

The US expectation was that the powerful military would switch sides. This, as we have seen, has not happened, at least not yet.

And negotiations were not part of the plan: "The only thing to negotiate with Nicolás Maduro is the conditions of his departure," the state department said of the Oslo talks.

Neither, for now it seems, is military intervention, despite threatening rhetoric that "all options are on the table".

But a number of Venezuelans told me they were open to outside intervention, despairing of any other solution to the political impasse.

"We need the Marines," said one elderly man, condemning government ministers as "bloodsuckers" and dismissing the Guaidó-led opposition as ineffective. "Why aren't they here yet?"

The opposition has organised protests but Mr Maduro has resisted calls to go

Another elderly man in the same neighbourhood also had little use for the government, but he was a supporter of the left-wing political ideology associated with former President Hugo Chávez and ostensibly shared by his successor.

"I'm still a Chavista," he said, then paused. "Why am I still a Chavista?" he asked rhetorically, "even I don't know."

Perhaps, I suggested, he was not a "Madurista."

As in all failed states, there is wealth - some comes from old money, some from new money acquired through corruption or by those who have otherwise benefited from their ties to the regime.

We stayed in this bubble of affluence, at a five-star hotel that has seen better days.

I had a severe allergic reaction to the dirty air filters, but there was water, power, and internet. It was paradise.

Social organizations distribute food to children in need in Caracas

For Maria there is only Petare.

She manages to get work as a seamstress, but it's all about patching old clothes, no one can afford new ones. And if people need zippers, forget it, they are no longer to be found.

I marvelled at how she could fix the piles of rags in her small, dank shop, some of which had more holes than cloth.

But she does, earning a bag of rice or flour with each one - five or six bags with 12 hours of work. She leaves at three in the morning, catches a few hours of sleep, and gets up again to cook for the children.

- Published5 August 2024

- Published12 August 2021

- Published4 February 2019