The Chile school where pupils carry petrol bombs over pencils

- Published

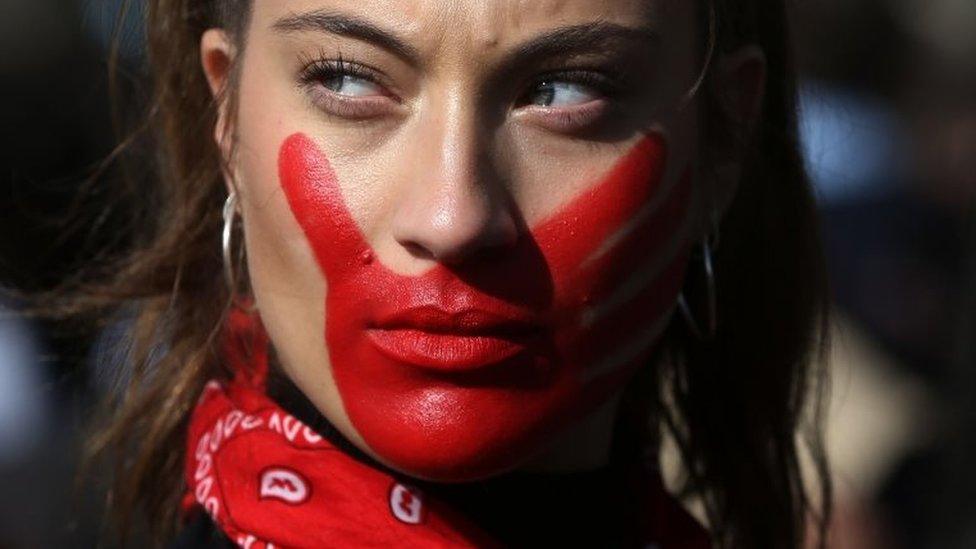

Pupils opposed to the Aula Segura policy have been involved in violent clashes with the police in the capital, Santiago

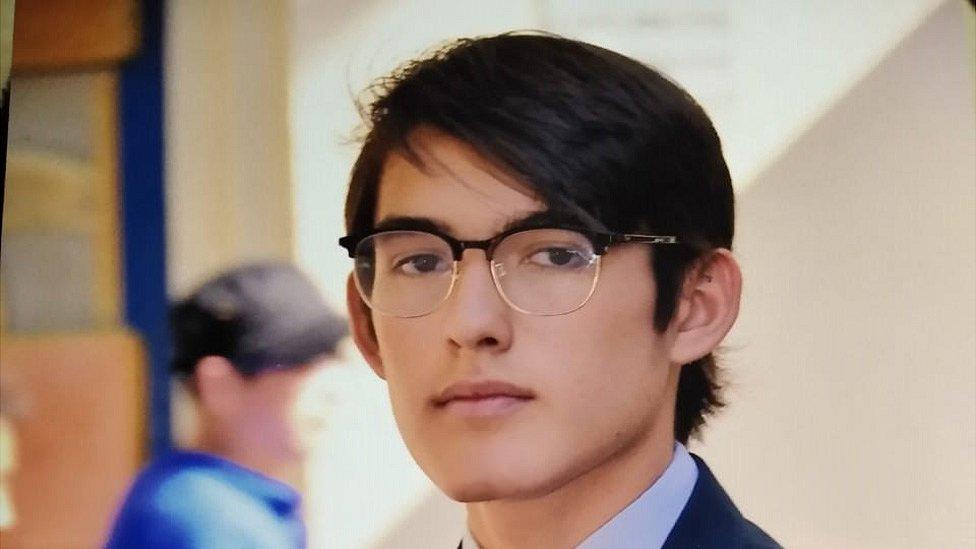

"No student throws a Molotov cocktail, just because they feel like it and think that it's fun," says Rodrigo Pérez.

The 17-year-old is president of the student association at the Instituto Nacional (National Institute) in Chile's capital, Santiago. He is talking about the motivation behind his fellow students' behaviour.

Rodrigo Pérez does not agree with the methods used by the masked pupils but understands their concerns

The boys' state school is one of the country's most prestigious. It has a stringent selection process and boasts a number of former presidents as alumni.

But over the past few months, the school has hit the headlines less for its academic achievements and more for the action of some of its pupils, who have thrown petrol bombs from the school's roof and taken over classrooms.

Tear gas and water cannons were used to break up some of the most heated protests.

Pupils say the police response was over the top

The school has installed security cameras and police search the bags of pupils as they enter the premises in order to prevent a repeat of the most destructive incidents, which were led by students who hid their identity behind masks.

A handful of other famous boys' state schools have also taken part in protests, but the Instituto Nacional is the most extreme.

'Fed up with labels'

"It's like a pressure cooker which has finally exploded and led them to this kind of violence," says Rodrigo of those who are protesting.

He may disagree with the methods the masked students are using, but he understands their motivation only too well: "My school reflects the state of education in Chile - a lack of resources and care for the students."

You may also be interested in:

There are complaints of rat infestations, blocked bathrooms with sewage leaking, cold showers, broken windows, leaking roofs and bullying teachers.

"We have been asking for the last six years for things to change. We are fed up with being labelled as terrorists and delinquents, when all we want is to be heard." he explains.

Pupils say the classrooms are in a dismal state

The masked students - like many other pupils at the school - want more resources to be pumped into their school, including enough teachers and a reform to the national curriculum, which they say is too old fashioned and does not reflect 21st-Century thinking.

Some pupils think the only way to get people's attention is to throw petrol bombs and take over classrooms.

Long-running problem

Critics say that the problem of state schools suffering from underfunding dates back to the rule of Gen Augusto Pinochet in the 1970s and 80s when they were put under the control of local authorities, which they accuse of siphoning off the money earmarked for the schools.

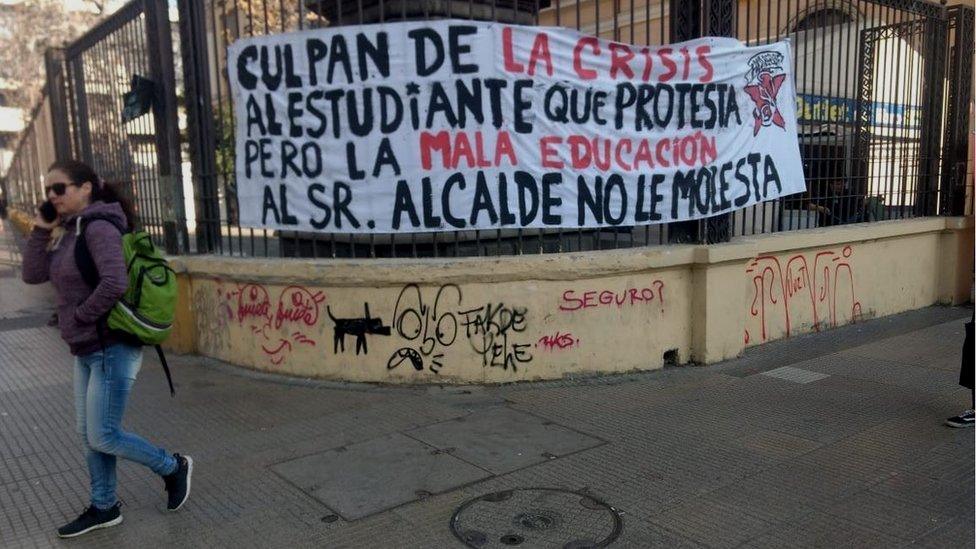

Teachers have also denounced the deterioration of public education

Felipe Alessandri, the mayor of the region where the school is located and who is in charge of the school's finances, rejects this. "Since, I have been mayor, every peso that I have been given has been used for the infrastructure of the school," he says.

He blames the students for the school's ill state of repair. "Every time we repair something, the students damage it. We fixed some of the bathrooms over the holidays and by the first afternoon of the new term they had graffiti all over them and were damaged."

The mayor is blaming the pupils for the crisis, angering them further

He argues that the troublemakers are a small group of highly politicised students out to cause disruption.

Mayor Alessandri believes tough measures are needed to stop them. "We can't have students pouring petrol on teachers and throwing bombs. We need to stop them," he argues.

'Heavy-handed policy'

His views are shared by the government of right-wing President Sebastián Piñera which has introduced a policy called "Aula Segura" (Safe Classroom) to contain the protests.

Under Aula Segura pupils suspected of taking part in violent protests can be excluded from school with immediate effect, even if their behaviour is still under investigation.

Rodrigo says this new measure - which sometimes results in pupils who have done no wrong being suspended - is heavy handed and has further antagonised already disgruntled students.

He says that it has also caused the number of masked protesters to swell from around 20 to 100 out of a total student body of 4,000.

"When the state dictates its policies by force, with police invading the school to remove students and using tear gas and water cannons, it's showing us that violence is their answer to the situation and that generates resistance," Rodrigo argues.

Deep divisions

Parents are divided about how to deal with the problem, with three parent associations taking different stands.

Judy Valdés leads one of them. "Even the students who throw Molotov cocktails have rights, because they are children who are still growing and that is what the mayor and the government don't understand," she says but stresses that she does not agree with their methods.

Ms Valdés wants to see more therapists in the school to help deal with the depression and other mental health problems many of the students are experiencing .

The pupils themselves say that attending class can sometimes resemble entering a war zone and that even those not actively taking part in the protests can get caught up in the melee.

Natalia Canales Riquelme's 14-year-old son Santiago is one of them.

Santiago got caught in the middle of a protest and was trampled by students fleeing from police

Santiago "wasn't masked, he wasn't throwing stones, he doesn't even know how to turn on the gas cooker, let alone throw petrol bombs," his mother says of the day he almost died when he got caught in the middle when police confronted the protesters with tear gas.

"I was nearly suffocating, I thought I was going to die. When we finally managed to get out of the courtyard I fell over and all the other students trampled me as they rushed to get away," Santiago recalls.

Mayor Alessandri says that he is listening to the demands of the pupils and their parents and that he is trying to find the money needed to modernise the school.

But with emotions running high among the students it is not clear whether the mayor's promise of improvements will be enough to convince them to stop the protests.

- Published13 March 2019

- Published7 June 2018