Fears stoke backlash against Venezuelans in Peru

- Published

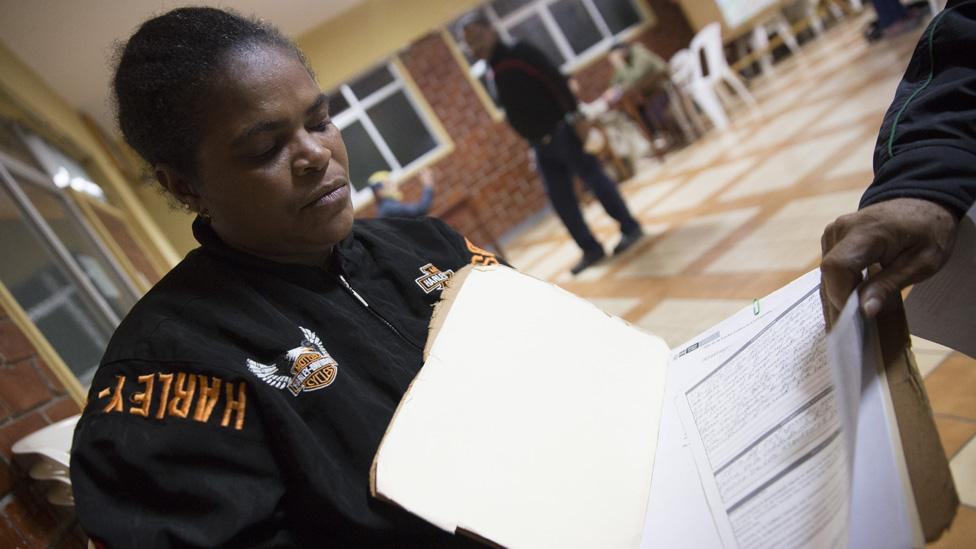

Pedro Carreño and his wife Iris Mendoza are trying to build a new life in Lima

When Iris Mendoza and her husband Pedro Carreño fled Venezuela, Peru's capital was their light at the end of the tunnel.

Mr Carreño had been diagnosed with severe cancer and Venezuela's collapsing medical system meant he could not get even the most basic care.

But when they arrived in Lima after journeying across South America they were met with a rising wave of xenophobia against Venezuelans like them arriving at the country's border.

"They look at you and they tell you that you should go back to your own country," Ms Mendoza says.

"They say: 'What are you doing here? We don't need any more Venezuelans here. We're full.'"

Millions of Venezuelans have fled the economic and political crisis in their home country, many of them to Peru, which is the second largest recipient of Venezuelan migrants after Colombia.

Of those, more than 80% arrived in Lima searching for work, aid, or, in Ms Mendoza and Mr Carreño's case, medical treatment they could not get anywhere else.

Backlash

But the unprecedented surge in migration this year has brought with it an equally unprecedented backlash.

"At the beginning, we had this very welcoming culture in all sectors of society," says Luisa Feline Freier, professor of political science at Lima's Universidad del Pacífico. "But then the fear started to kick in."

According to a June poll by the Institute of Peruvian Studies, 73% of Peruvians are opposed to Venezuelans coming to Peru.

Increases in crime and migrants taking Peruvian jobs were among the top concerns, which Prof Feline Freier say are "based on fears more than on facts".

Venezuelans who have found jobs count themselves lucky, but some Peruvians fear their jobs are being taken away from them

Peruvian government data shows that in 2018 less than 1% of crimes in Peru were committed by Venezuelans. But the perception Peruvians have is very different.

More than half of those questioned in a study in February said they believed that "many Venezuelans engaged in criminal activities in Peru".

Prof Feline Freier says sensationalistic reporting and the rhetoric of public officials is to blame for these misconceptions.

Read more about the crisis in Venezuela:

Bad press

One of those concerned by what she sees on the news is Alejandrina Bardales. The 50-year-old owns a household goods stall inside a market in Lima.

Alejandrina Bardales worries that Venezuelans are offering lower prices for their goods

As shoppers bustle by, Ms Bardales explains that she wanted to welcome fleeing Venezuelans but "on television, you hear things, [such as] them doing damage to others, robbing".

Ms Bardales, who has run her stall for 25 years, says it is something that "has never happened around here".

She says she is also losing trade because Venezuelan traders who have set up business next to her stall are undercutting her. "They offer lower prices when they shouldn't and they take away my clients."

Many Venezuelans are having to resort to selling goods in the streets to make ends meet

According to figures by the International Labour Organization, 72% of Peru's workforce are employed in the informal sector, working in jobs without guaranteed income or benefits.

They are now being joined by Venezuelan migrants desperate to make ends meet.

Iris Mendoza says that she has had to resort to selling candy and cleaning houses for a fraction of what her husband's cancer treatment costs.

"I've been able to work cleaning homes of families, and they pay 20 soles ($6; £5) a day from 8 am to 5 or 6 pm," she said. "Twenty soles. That doesn't even get close to what we need to survive."

'Forced to beg and cry'

Ms Mendoza and Venezuelans like her compete with the Peruvian workforce, which has spurred on hostilities across the country.

The money Ms Mendoza earns is not enough to cover her husband's medical bills

Politicians have latched onto those tensions. In June, President Martín Vizcarra stood in front of an airplane being boarded with soon-to-be deported Venezuelans and announced the introduction of a new visa with tougher restrictions on Venezuelans entering the country.

"We have to take actions to improve and guarantee the security of the citizens of Peru," he argued.

While he named it a "humanitarian visa", experts like Prof Feline Freier dubbed it something else: a "socio-economic filter" that will only further rile xenophobia against Venezuelans.

Peru has tightened its immigration controls and Venezuelans now need a visa to enter

Already, Peru is seeing the fallout from those festering tensions. Following reports of a Venezuelan killing an elderly man in the central city of Huancayo in late July, Peruvian residents took to the streets shouting "Venezuelans have 24 hours to leave Huancayo" and burning the belongings of migrants.

The city's mayor echoed their chants, saying "let the bad Venezuelans go to hell".

But migrants like Ms Mendoza have their minds set on moving forward and surviving the day-to-day. "This place has humbled us a lot. You feel tired. Sometimes you're forced to beg and cry."

Ms Mendoza said she "never dreamed of leaving" Venezuela but as the economic and political crisis continues to deepen, leaving many without light or even the most basic food supplies, the medical care her husband needs virtually does not exist. Returning for them is not an option.

"We Venezuelans aren't here because we want to be, we're here because of the situation in Venezuela has pushed us out," she said.

More on Venezuela:

What are the real reasons behind Venezuela’s blackouts?

- Published26 July 2019

- Published30 March 2019

- Published11 March 2019