Argentina election: Voters dream of breaking cycle of crisis

- Published

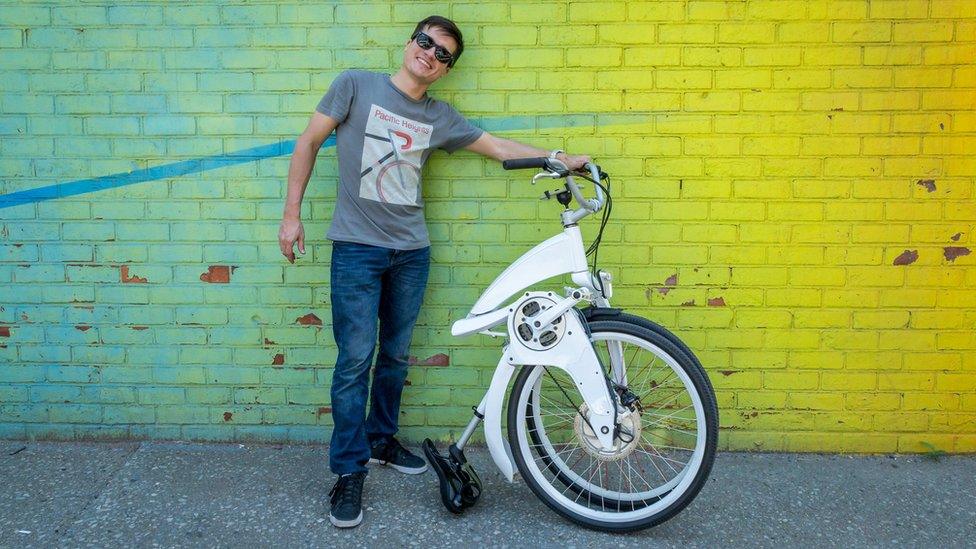

Lucas Toledo got the idea for the quick-folding Gi Fly electric bike during a transport strike in 2015

"It's like trying to run an ice-cream parlour in the desert."

That is how entrepreneur Lucas Toledo describes the uphill struggle of having a business in Argentina.

With a hugely polarising presidential election only days away, the country is in the middle of another economic crisis.

This comes 18 years after Argentina's debt default in 2001, when the South American country went through five presidents within a fortnight after a run on the banks.

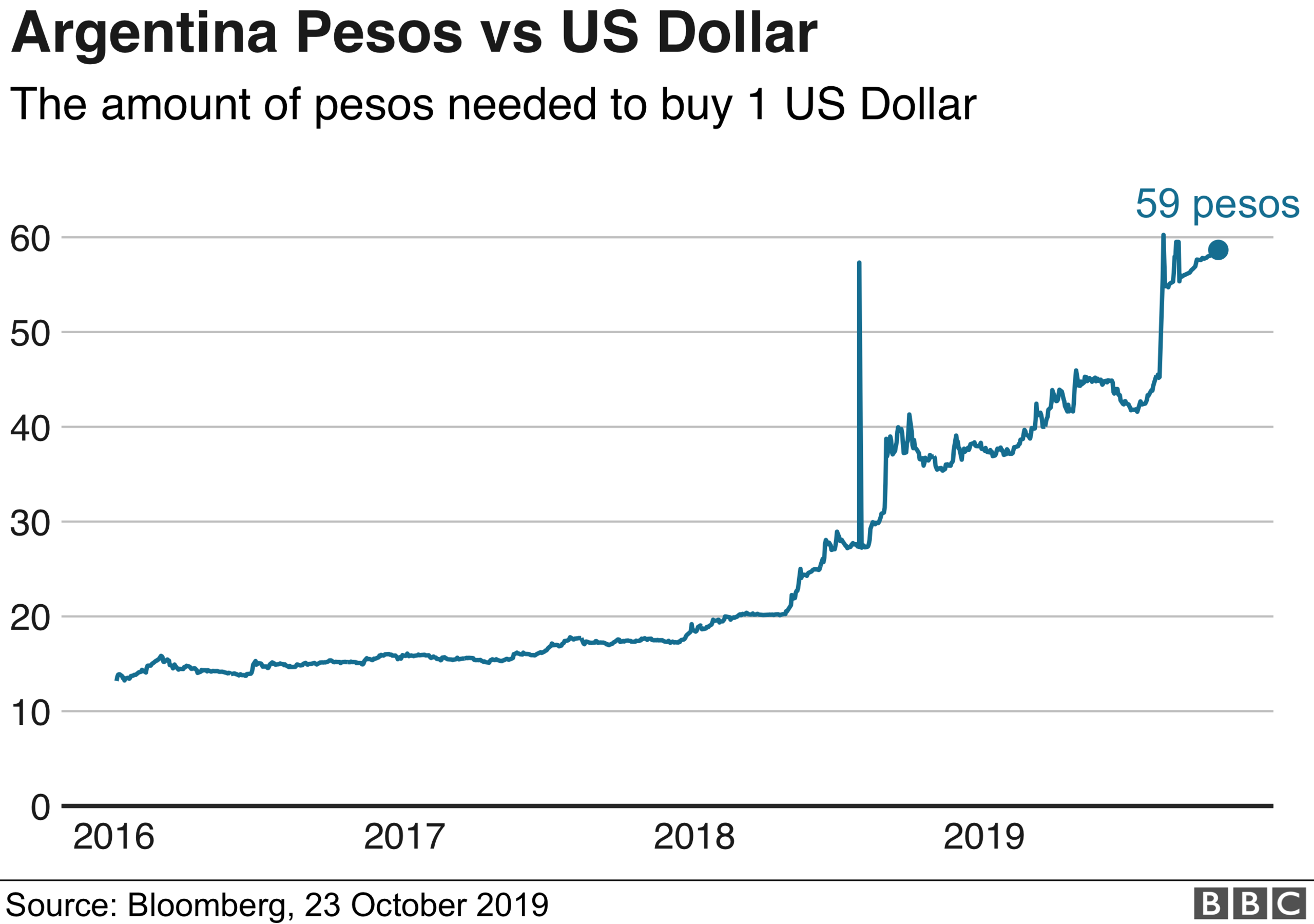

It may not have come to that in 2019, but the inflation rate has surged beyond 50% and the currency has plummeted.

Who is to blame for this return to bad form? It depends who you ask.

Some say the villain is the current right-wing president, Mauricio Macri, while others point the finger at his predecessor Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, who is running for vice-president in Sunday's election.

Argentina's election in short

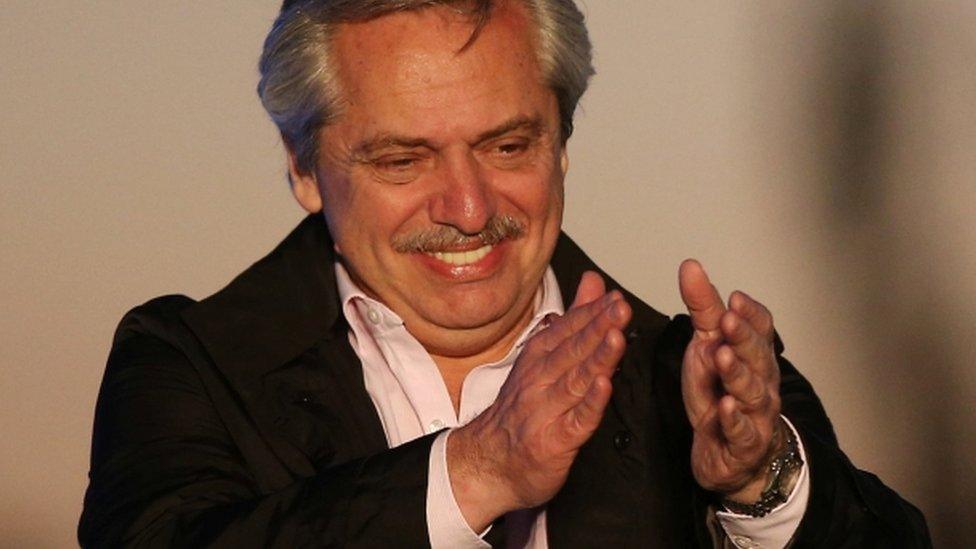

Incumbent President Mauricio Macri, a right-wing businessman, is facing centre-left challenger Alberto Fernández

Mr Fernández's running mate is former populist President Cristina Fernández (no relation)

To avoid a run-off, the candidate needs to secure 45% of votes (or 40% and a 10-point lead)

She and her centre-left running mate - presidential candidate Alberto Fernández (no relation) - belong to the populist Peronist movement.

Mr Toledo is firmly in the pro-Macri camp. He has been campaigning for the president's re-election while running his state-of-the-art electric bike company, Gi Fly, from Córdoba, Argentina's second biggest city.

He says that Mr Macri, the ex-president of Boca Juniors football team, is the more business-friendly candidate. The president has shown specific support for the Gi Fly bike, having once been pictured riding one to promote home-grown innovation.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

The bike is a clever contraption. It folds down in a second and can be locked automatically from a smartphone.

But at US$2,729 (£2,160), it is also very expensive. The small company exports mostly to the US, but benefits from using affordable local engineers in its home city for development and then outsourcing production to China.

Could the company operate solely in Argentina? Mr Toledo laughs: "That would be 100% impossible."

He says the biggest problems for entrepreneurs are Argentina's inflation rate and high taxes. The government, which is in a minority in Congress, has tried to reduce taxes, "but when they bring in new regulation, it gets blocked".

While Mr Toledo acknowledges that the Macri administration - in power since 2015 - has made plenty of mistakes, including failing to bring down inflation and poverty, he is convinced it is better than the alternative.

An election battleground

Industrious and relatively wealthy, Córdoba province was the only voting region - aside from central Buenos Aires - that backed President Macri in August's primary election.

In Argentina, the primaries feature numerous cross-party candidates, and function as a culling process but also a dry-run for the main event.

In Córdoba, this sparked a parody Twitter account, calling for a separatist movement - a Brexit for Córdoba, or a "Cordobexit" - and both leaders have made repeated trips to the area to try to drum up support.

Nationwide, Alberto Fernández won 47.7% of the votes, as opposed to Mr Macri's 32.1%, and analysts say the president's chances of staying in power now look very slim.

"Macri came along with his Cambiemos (Let's Change) slogan, but nothing really changed," says Guillermo Beney, another entrepreneur from Córdoba.

Mr Beney does not want to say who he will vote for on Sunday, only revealing that he considers his chosen candidate as the least bad option. Voting is compulsory in Argentina so he has to pick someone.

Guillermo Beney and Maria Celia Tuta founded Fernet Beney

Mr Beney's small business sells organic fernet - a liquor that originated in Italy but which has become immensely popular in Argentina, particularly in Córdoba.

He thinks the company would be a lot bigger by now if it were based in what he calls a "normal country". This is a sentiment echoed by many Argentines who say they are fed up of living in a resource-rich country that remains so financially troubled.

Mr Beney's business was hit hard by the 2001 economic crisis. "We were just starting out then, we hadn't balanced the books yet, and it was impossible to get a loan," he recalls.

His company survived that particular tough run, but the experience had a lasting effect on how he does business. He says he has avoided taking credit ever since and, for that reason, only provides orders to small stores and not supermarket chains.

He and his partner, Maria Celia Tuta, also pitch their fernet bottles largely at tourists.

Tourism, he says, is one industry that tends to ride out a crisis. "Brazilians, Chileans and people from all over the world are all coming because the exchange rates makes it cheap for them," he explains.

"And Argentina's middle classes, who used to go to Brazil more for their holidays, are now staying here too."

Surviving economic storms

People from Buenos Aires often choose Córdoba for a break on account of its green valleys, and to escape the capital's humidity.

The province has pockets of microclimate - where the air is dry and the temperatures are more moderate - and some people have joked that these have extended the region's growing software industry, which can weather economic storms better than traditional manufacturing work.

"That's true," says Natalia Giuliani, co-founder of a software company in Córdoba city. "Many focus internationally and can benefit from operating in dollars."

Natalia Giuliani says that when politicians don't think long term, people can't plan their lives

However, that does not apply to her own business, which targets entirely Argentine clients and is tied to its beleaguered currency, the peso. She says she is constantly renegotiating contracts and salaries to keep up with rocketing inflation. "Lots of our costs - servers and licences etc - are priced in dollars, which is a real challenge."

Ms Giuliani says she will be voting for Mr Fernández on Sunday, because although President Macri portrays himself as the pro-business candidate, she feels his policies are not working for anyone.

"No-one has any money now. Everyone is worried all the time. That can't be good for business."

She also thinks a Fernández administration would be more likely to prioritise tackling rising poverty.

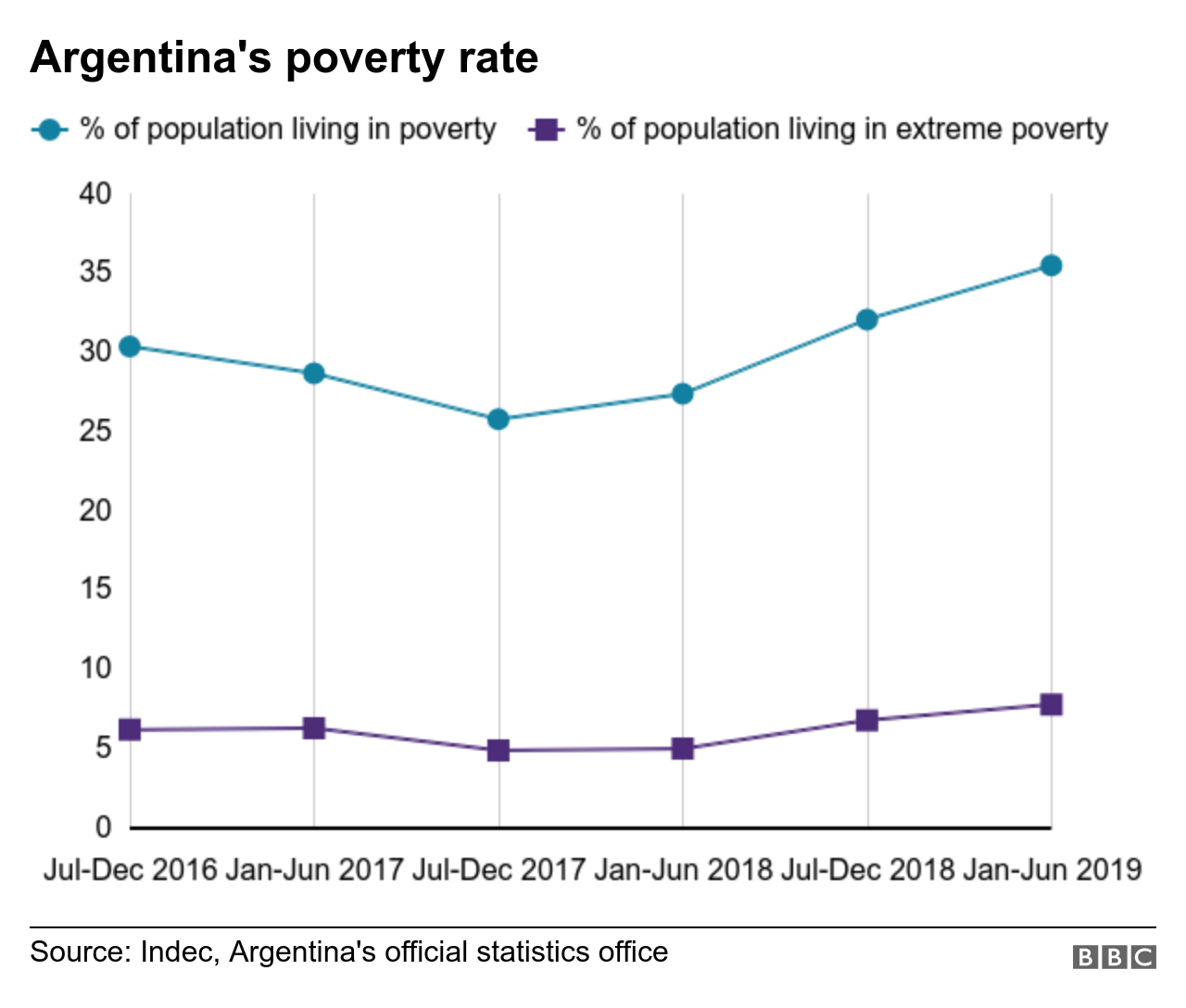

Mr Macri pledged to bring the percentage of the population living in poverty down to zero in his 2015 campaign, but in the first half of 2019, the rate jumped to 35.4%.

Critics have compared this to much lower figures at the end of the previous government, although it is hard to make direct comparisons as that administration's statistics have been widely derided as unreliable.

Mind the crack

Ms Giuliani knows a lot of her friends and colleagues in Córdoba will be voting for President Macri, mostly, she says, because they fear the alternative.

Political lines in Argentina are firmly entrenched. They call the divide "la grieta" (the crack), and election choices can be as divisive here as a vote for Brexit in the UK or for Donald Trump in the US.

However, she says even those who would never back the Fernández-Fernández ticket still want change, as almost no-one is happy the way things are going.

She worries that the difficulties can not be solved when politicians only concentrate on short-term political gains, and she fears whoever is in power next could end up juggling the old issues, "like a hot potato", before passing them on again.

"When there is an election, the colours of the party in office may change," she says, "but we can't seem to get away from the same problems."

- Published2 September 2019

- Published28 October 2019

- Published14 August 2019

- Published13 August 2019