Bolivia election: An uncertain future for Evo Morales

- Published

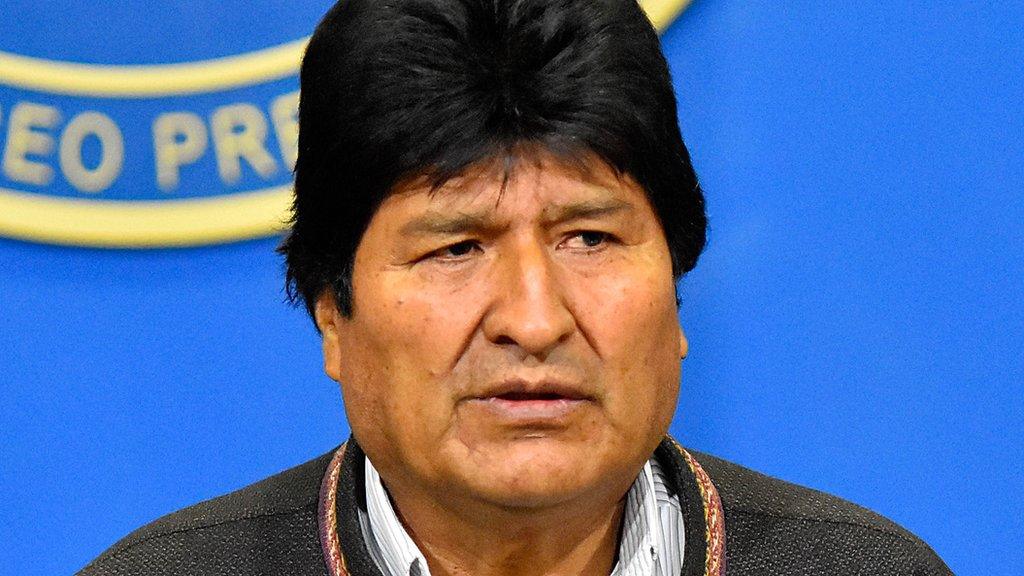

With almost 14 years as president, Mr Morales is running for a fourth consecutive term in office

From the windy city of El Alto, high up on the altiplano above La Paz, you can see the formidable and much revered mountain of Illimani. The craggy and snow-capped peak dominates the Andean skyline.

It is here in Bolivia's second city that President Evo Morales chose to celebrate the end of his election campaign. El Alto was crucial in his rise to the top back in 2006 - a city made up mostly of indigenous Bolivians who had migrated from rural areas. Mr Morales himself was the first indigenous president Bolivia has ever had.

At the ceremony, people waved blue flags - the colour of his MAS party (Movement Towards Socialism). To keep the revellers warm, stall-sellers with big cauldrons offered what is known as "te con te" (tea with tea), a hot toddy made of Singani, a Bolivian liquor, mixed with lemon, cinnamon and sugar.

"I always dreamed of a government that fought for the youth, for children, for rural Bolivians," says 60-year-old Rebeca Choque. She has lived in the US state of Utah for more than 30 years but came back to support the leading candidate in winning a fourth term as president.

"They've always been forgotten and left behind and the world looked at them as lazy, ignorant, dirty people."

Next to Rebeca is her mother, Dominga, who is dressed in a full skirt, or pollera, and a bowler hat typical of indigenous Bolivian women. "If he doesn't win, it will be back to the old times - the other parties are not like him, they don't think about people, they just think about power."

Evo Morales is one of the longest serving leaders in Latin America

Evo Morales was a fresh start for the country, promising that Bolivia's poorest, mostly indigenous, communities would have a bigger voice than in the past.

"That's really changed the narrative of this country," says Marcelo Arequipa, a political science professor in La Paz. "It's transformed it - it's elevated the self-esteem of Bolivia."

Not only that, but for much of Mr Morales' rule, the economy has grown an average of 4.9% per year, external.

"Fundamentally, his success has been economic," says analyst Roberto Moscoso. "He's taking advantage of the commodities boom and that has been well-managed politically by Evo Morales."

Crisis to come?

But many analysts point to an impending crisis. No gas reserves have been found during Evo Morales' time in office and mineral prices are falling. Add to that, his government has been accused of corruption and this past mandate has been the most controversial.

In 2016, he lost a referendum seeking to lift term limits. Bolivia's constitutional court subsequently ruled that the decision violated candidates' human rights so he could stand for another term.

Supporters of President Morales take part in a rally in El Alto

"There's an economic problem but fundamentally one of democracy," says Mr Moscoso.

"People recognise his achievements - you ask people in street if he's achieved anything and most will say 'Yes, the economy, social inclusion, social justice'. Do you support him? 'Sure I do.' But ask them if they agree he should be president again? 'No because he's already been president.'"

Soledad Chapeton is proof of how El Alto is changing. The first female mayor of the town, the man she unseated belonged to the ruling MAS party who was subsequently given a prison sentence for corruption.

"People in El Alto are demanding. We're humble but our patience has limits," says Ms Chapeton.

"The government used to give us money as if it was a favour when, in reality, it's an obligation. And so people started waking up to the fact that political discourse isn't going to resolve issues like water and sewage shortages. The national government has got drunk on power and when you're drunk you miss lots of things."

El Alto Mayor Soledad Chapeton: "The national government has got drunk on power"

Evo Morales' closest rival in the presidential election is former President Carlos Mesa. In his campaign video he tells Bolivians enough is enough - the health system is at the point of collapse and money is being wasted.

"Carlos Mesa represents democratic and institutional values, a respect of the constitution in the face of a government that has, in its most recent term, been characterised by violating the constitution, laws and institutional order," says his political co-ordinator José Antonio Quiroga.

He admits though that Mr Morales' government was not all bad. "This government has shown that it can control its natural resources with more national sovereignty and there has been a coup in securing national dignity," he says.

Former President Carlos Mesa (right) is Mr Morales' main rival

"But it could have been done without violating laws and the constitution, without going after opponents. It's imposed a project of power, rather than one of social transformation. And this government has ended up doing the same as its predecessors, only in a different way and with a change in elites."

So what next if Evo Morales wins?

"There really is nobody on the horizon who has anything like the charisma that he's had," says Robert Albro, a Bolivia expert from the American University in Washington DC. "Morales thinks he's the historical figure, the change agent. As time marches on, he's increasingly wrong. You can't continue to be there, someone else has to take over."

You may also be interested in:

Bolivians embark on long protest march over fires

- Published10 November 2019

- Published7 February 2023