Mexico's bid to detain El Chapo son 'a failure of everything'

- Published

Two of the many vehicles burned out during the clashes

Even to a nation hardened to drug war images, the scenes in Culiacán were shocking.

Scores of cartel gunmen shut down the streets and engaged in sustained battles with the armed forces. Vast patrols of military vehicles descended on the neighbourhood of Tres Rios.

There were burning cars, roadblocks and heavy weaponry being fired in the middle of the day in the centre of the commercial district of the city.

There soon followed equally disturbing images of people - families with children - diving for cover.

"Can we get up now?" one child asked her father as they cowered behind the wheels of their car. "Not yet, darling," he replied, his voice strained and frightened.

Elsewhere, mobile phone footage emerged of panic inside a shopping mall, the rapid gunfire audible in the background.

Once the smoke eventually lifted, the explanations began.

The state government's initial reasoning posed more questions than it answered.

Speaking on television, the State Security Secretary, Alfonso Durazo, claimed the police had discovered the wanted leader of the Sinaloa Cartel by pure chance when a routine patrol was fired on from a house.

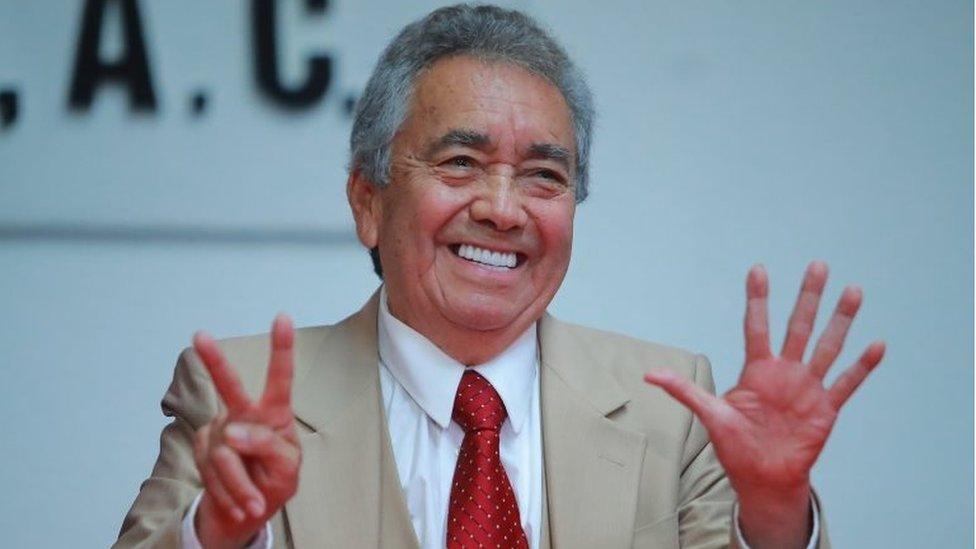

The Guzmán family lawyer says thank you

On entering the building, they identified one of the men inside as Ovidio Guzmán López , the son of the notorious former head of the organisation, "El Chapo" Guzmán, currently serving life plus 30 years in the US.

Yet that didn't seem to tally with eyewitness reports and videos of an apparently co-ordinated operation.

What's more, Mr Durazo was deliberately ambiguous as to whether or not they still had "El Chapo's" son in their hands.

It soon became evident that they did not. They had let him go.

Watch clashes between Mexico's security forces and drug cartel members

It was a huge embarrassment for the government. They had captured one of the most wanted men in Mexico and, outgunned and overwhelmed by the cartel, they simply turned him back over to his men.

By the following morning, both state and federal government were on damage control.

"This was a failed operation," Mr Durazo admitted, "a rushed operation." The police had acted without orders from above and the decision to release Guzmán was only taken to prevent further violence to the civilian population, he argued.

"We are not going to convert Mexico into a greater cemetery than it already is."

Forensics on the case the day after in Culiacan

Mr Durazo could at least count on a similar song-sheet being sung at the federal level. In his daily press conference, President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador said he wasn't only aware of the decision to let "El Chapo's" son go but approved it.

"The capture of a criminal cannot be worth more than people's lives. They took that decision and I supported it," he said with characteristic defiance.

There were extenuating circumstances, the government points out, in that a number of military men were taken hostage by the cartel.

Yet whether any of them were killed or harmed is another of the murky details that remains undisclosed in this debacle.

As does an apparent prison break. In the middle of it all, dozens of inmates at the Aguaruto prison escaped amid the confusion. Mobile phone footage shows them pulling drivers from their cars and making their getaway.

With the state authorities suggesting the police patrol which detained Guzmán acted without authority from above, the mayhem in Culiacán could be seen as a failure of co-ordination by the state, of planning or intelligence.

"It was a failure of everything," says Professor Raul Benitez, a security expert at the National Autonomous University in Mexico (UNAM).

"What it showed was the great power and control that the Sinaloa Cartel still exercises over the city of Culiacán." The shocking scenes bury the theory, he says, that the group is "bruised or broken after El Chapo was imprisoned in the United States."

Despite the chaos in Culiacán, President Lopez Obrador insists his approach of non-violence towards the drug gangs remains the right one. "We don't want a war," he said.

Maybe so - but this week's spike in drug-related violence in several states in Mexico shows they are still in a war all the same.

At least eight people were killed

There was an ambush on a police patrol in Michoacan in western Mexico which left 13 police officers dead on Monday and then an apparent clash between cartel members and the military the following day which left another 14 dead.

The policy under previous governments of all-out war against the cartels was misguided, says Professor Benitez. However, he believes so is the "softly, softly" strategy by the current administration.

Now the fear is that other cartels in the country will have learned an important lesson from what happened in Culiacán.

"The Gulf Cartel and the Jalisco Cartel must be pleased," Professor Benitez said. "Now they know what to do when one of their leaders is lifted: bring out their biggest guns and sow chaos and anarchy."