Loved to death: Turks and Caicos' battle to save the queen conch

- Published

From a staple food to its use as a musical instrument, few things epitomise the culture of the Turks and Caicos Islands (TCI) like the queen conch.

And, for tourists, pulling up to a beachside restaurant to sample the freshly caught marine snail is a bucket list feature, the creature having been omnipresent in the islands' shallow translucent waters for centuries.

Except, for several days in January, there were none to be found.

Overfishing is being blamed for plummeting ocean stocks which saw conch off the menu at several restaurants across Providenciales.

Fears are now rife that the beloved mollusc, which even appears on the British territory's coat of arms, is being loved to death.

National symbol

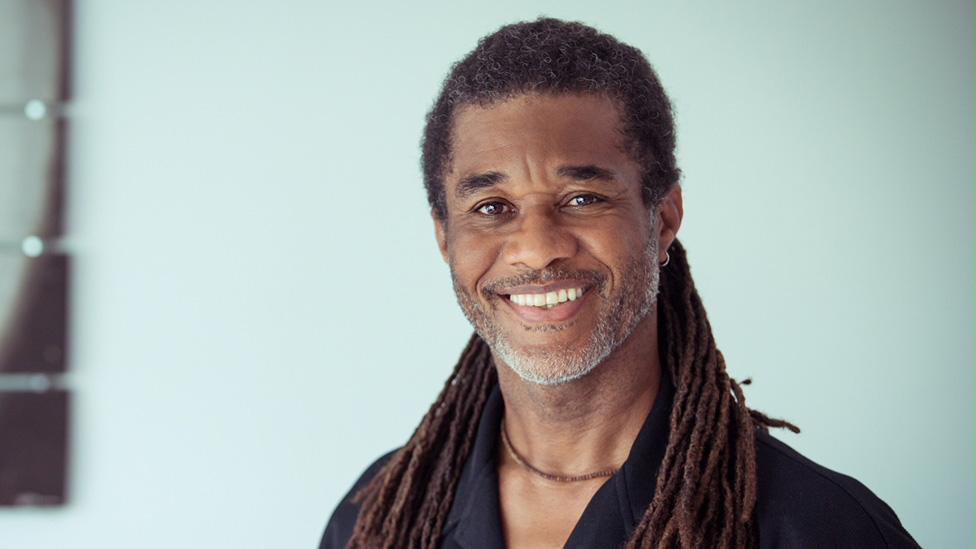

"Conch is a national symbol and a huge part of our heritage," explains TCI's former culture director David Bowen.

Conch blowing is part of TCI's cultural heritage

You may also be interested in:

"When I was a kid, every time we got in the ocean we could see conchs. I had friends visit for Christmas and they went to a restaurant to try conch and were told there wasn't any."

David Bowen worries about the future of conchs

Mr Bowen blamed a lack of action from the government, which still permits conch to be exported, along with watersports operators who allow holidaymakers to take home live juvenile conchs as souvenirs.

Conchs can be found in shallow waters

"They assume conch is unlimited but environmentalists have been warning about this for years," Mr Bowen added.

Conch has at times been the islands' biggest export. Florida, which is just 600 miles (965km) away and which has itself banned conch fishing for decades due to its own shortages, is a prime customer.

Turks and Caicos' annual conch exports have topped one million pounds (453,600kg) of meat in years past, equating to roughly 200,000 animals.

Something special

Many argue the practice is no longer sustainable.

"Conch is a delicacy and should be preserved," said John Macdonald, owner of Da Conch Shack restaurant in Providenciales.

"People take it for granted but we believe it's something special to try, not to be eaten for every meal. If we'd stopped exports years ago we'd never have had these problems," he continued.

Mr Macdonald said the restaurant's sea-based crawls which catch wild conch had been empty for several days.

Michael Stolow, owner of Bugaloos restaurant, told the BBC his fishermen were being forced to hunt further and for longer to find conch.

He said the eatery was receiving several calls a day from hotel concierges inquiring if conch was on the menu.

Conch is a sought-after delicacy used in salads...

...and made into fritters

"Many tourists have already been to other restaurants and found none available, so now they're calling before they even get in the cab," he added.

The shortage is echoed across the Caribbean with one study in neighbouring Bahamas suggesting the country could lose its conch industry entirely within a decade without urgent action.

Last year, Jamaica implemented a ban on all conch fishing amid a dramatic decline in stocks.

Call for blanket ban

TCI does have an annual three-month "closed" season on exports but environmentalists say it falls far short of what is required.

Kathleen Wood, of research body SWA Environmental, has been calling for tighter controls for years and now thinks a blanket ban is the only way to save the species.

"It's horrific that we've reached this stage. If fishing persists, it might be too late to do anything," she said.

Conch's importance to Turks and Caicos dates back to the pre-Columbians who not only ate them but fashioned their shells into tools.

Later, islanders used them as musical horns while the shells' beautiful pink colours have seen them displayed in jewellery for centuries.

Conch is also used to make colourful jewellery

There has even been a long-running festival devoted entirely to the meaty mollusc, featuring a host of innovative dishes and a lively "conch knocking" contest in which participants race to remove the creature from its shell.

The queen conch has been under the protection of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) since 1992 which offers some levels of protection regarding trade.

Under pressure

Conchs are particularly vulnerable to overexploitation, due to their slow mobility, habitat in shallow, accessible water, and slow growth and reproductive cycles.

By grazing on algae which can smother coral reefs, they play an important environmental role too.

But their numbers have to be at a certain density to enable them to reproduce, explained Chuck Hesse, who founded the islands' erstwhile Conch Farm in the 1980s.

"The female conch, like a cat, gives forth a pheromone to attract the males. If there are no males downstream to smell it, mating will never occur," he said.

Environment Minister Ralph Higgs acknowledged conchs were "under pressure".

He said measures being taken included reducing the number of fishing licences granted, along with slashing export quotas.

An ocean stock count is currently underway, after which final decisions will be made on carving a path forward, Mr Higgs added.

That cannot come soon enough for many islanders.

"Once conch have gone they don't come back; that's what's happened everywhere else," warned Mrs Woods, adding that Florida's long moratorium on conch harvesting had done little to bring numbers back to a commercially sustainable level.

"For Turks and Caicos, the biggest impact is the loss of an iconic cultural species. For a country to lose a piece of its national identity is tragic."

You may want to watch:

Event organisers say the tradition of conch blowing goes back to the 1800s in Florida

- Published19 July 2018

- Published3 February 2017