Coronavirus in South America: How it became a class issue

- Published

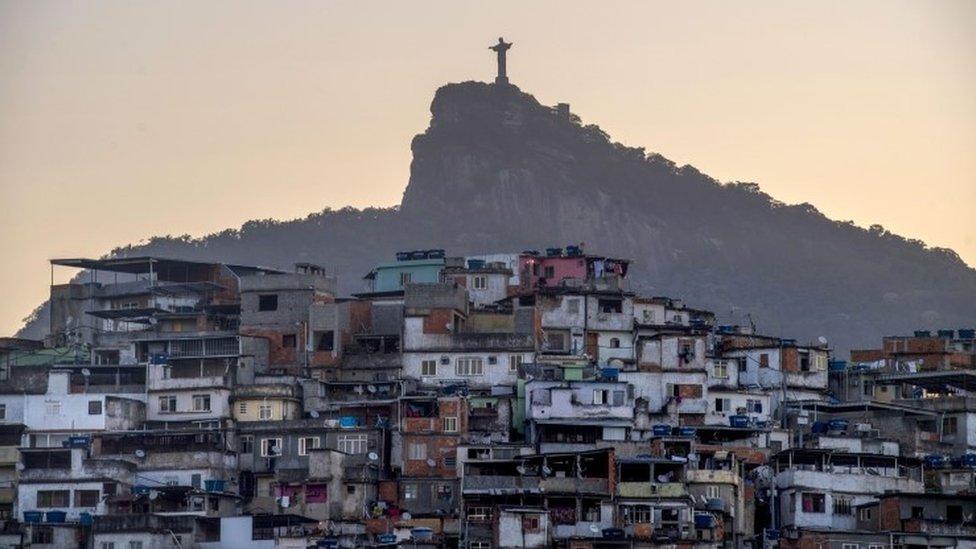

There are now cases being reported in Rio's favelas

Brazil got its first case of coronavirus just after carnival. The man, who had visited Italy, returned with symptoms and went straight to Albert Einstein hospital, a world-class institution in the southern hemisphere's biggest city, São Paulo.

In the beginning, many of the cases followed a similar pattern, affecting Brazilians who can afford to travel abroad and pay for treatment in private hospitals.

And it is a pattern that is replicated across the region too. The first case in Ecuador was somebody returning from Spain. In Uruguay, media reported last week that half of the country's coronavirus cases could be traced back to a single guest at a glamorous party who had just come back from Spain, external.

This has not escaped the notice of poorer Brazilians either, many of whom share the view that the virus is coming over from wealthier people who have been on holiday abroad.

Maria do Rosario Silva is a 50-year-old housekeeper who lives and works in the south of São Paulo. She was alarmed by the pattern of transmission she was hearing about on the news, but has now been sent home by her employer on full pay to stay safe.

"I'm not just a bit scared," she says. "I'm terrified, especially for older people and those who are who are vulnerable. If we don't control it, it will end in panic."

A SIMPLE GUIDE: What are the symptoms?

AVOIDING CONTACT: Should I self-isolate?

MAPS AND CHARTS: Visual guide to the outbreak

VIDEO: The 20-second hand wash

The story of the first person to die of the coronavirus in Rio de Janeiro has fuelled this fear. Just a few days ago, the investigative journalism website Publica reported that a 63-year-old housekeeper's employer had gone to Italy and came back with symptoms - and didn't tell her housekeeper she was ill. Fast forward a month, and the housekeeper is dead.

The speed of transmission is something that worries medics here, who fear the public health system will not be able to cope.

"The social class who is ill at the moment are the upper-middle and upper classes, and that's why we haven't yet seen a sustained transmission rate," says Dr Beatriz Perondi, who heads the disaster and emergency committee at São Paulo's Hospital das Clinicas, the largest public hospital in Latin America.

"Once they start spreading the virus to the middle and lower classes, that's when we are going to have issues with quarantine. With lots of people living in the same room, that could cause huge transmission problems."

It has already started - there are now cases in Rio's shantytowns, known as favelas. Hospital das Clinicas is preparing, opening up an entire floor to receive critical patients. In the next week or so, it is expecting half of the ward to be full, and in less than a month that every bed will be occupied.

Everything you need to know about the coronavirus in one minute

It's community transmission that reveals the deep inequalities in the region - poorer people serving wealthier ones. Cooks, housekeepers and nannies will have to rely on a public health service that is already over-subscribed - and that's without the onslaught of coronavirus.

And while decent employers will continue to pay their staff regardless of whether they will work or not, not everyone has been decent. I have been asked whether it is reasonable to pay a cleaner half a salary if they are no longer working - short answer, no, these are the people who need the money more than ever. In a country where 40% of the workforce is estimated to work in the informal economy, millions of poor people are going to bear the brunt of coronavirus.

The government has introduced emergency measures. Informal workers will each receive 200 reais a month (£33; $40). But Brazil's currency is plummeting each and every day. It is not enough to buy food for a month for a family, let alone cover rent and bills. This is a menacing virus, but just as menacing is the threat of hunger - how can these families live like this, and for how long?

As the health minister here said last week, we are at the foot of the mountain and we are about to start climbing it. But the route to the top will be far harder for some in this, the most unequal region in the world.

- Published23 March 2020