Why coronavirus could be catastrophic for Venezuela

- Published

Venezuela could be facing a perfect storm

Venezuelan state television usually consists of wall-to-wall coverage of the government's daily achievements, press conferences and rambling speeches by President Nicolás Maduro.

Folkloric music makes an appearance too but in these times of coronavirus, the lyrics are a little different. Traditional llanero musicians are no longer warbling about Venezuela's grasslands and unrequited love. Instead, they have switched to singing about washing hands, staying at home and donning a mask.

"Venezuela, beautiful homeland, stay calm, I beg you," sings Ysidro Salom who is wearing a cowboy hat and strumming a harp. "We know what we have to do because we are blessed. We need to be conscious and cautious to make sure we don't contract coronavirus."

This is a country that has been battered by years of economic crisis, hit by hyperinflation and bogged down in political chaos.

With a health system that is already on its knees, the arrival of coronavirus is a frightening prospect.

Quick to lock down

Within days of Venezuela recording its first cases of Covid-19 in the middle of March, President Maduro ordered a national quarantine to try and stop its spread.

President Maduro (in white) was quick to impose measures to stop the spread of coronavirus

"It's one thing for the president to say something, but it's another when it hits you," says 33-year-old Meybis Noguera, a supermarket cashier in Caracas.

"Throughout all these years, our health system has been in a terrible state and now with this pandemic, I don't think we're prepared at all."

Shortages of hospital and medicine supplies are widespread and there is no doubt the virus will make supply issues worse.

"We have about 80 intensive care beds in the country - Venezuela should have about 2,500," says Dr Freddy Pachano, a doctor in the state of Zulia and president of the National Board of Directors for Postgraduate Medicine.

The Venezuelan hospital where there's barely running water, let alone medicine

"Add that to the basic services we don't have in hospitals like constant electricity supply that ventilators rely upon. All of these elements together create a Dantesque scenario that could see lots of deaths in the country."

Day-to-day survival

Even before this crisis hit, millions were living hand-to-mouth. With quarantine, that situation is expected to get worse.

"Our bills don't stop, we still have to pay things like municipal taxes every month," says sweet stall owner Christian Croes.

"My biggest worry though is food. There comes a point when we don't know how long we will survive with no income. If there's no money coming in, you can't even buy the basics."

Many Venezuelans rely on the informal economy to survive. Henkel García, director of Econometrica consultancy, estimates it is between 40% and 50% of the workforce.

A large part of the population works in the informal sector

"The next few weeks will be full of tension," says Mr García. "Even if social distancing keeps the number of cases in Venezuela relatively low, as the days go by it's going to get more complicated."

Fuelling the economy

Increasing petrol shortages are adding to people's daily stress. Venezuela's crumbling refineries and US sanctions mean the country with the world's biggest oil reserves is now running out of fuel.

These doctors used the time they spent queuing for fuel to eat a snack

Every day before dawn, key workers - including doctors and nurses - are now having to queue for hours at the few gas stations that still have fuel to sell.

Queues like these are common across Venezuela but not until recently in Caracas, which was traditionally better supplied than other parts of the country.

José Davila delivers drinking water to houses in the southeast of Caracas. He only works three-and-a-half days a week now because business has slowed.

Water has been hard to come by in Caracas

Restaurants and offices are shuttered up. Add to that, he is one of those people who cannot get enough petrol to do his job properly now either.

"It's hard to move around the city safely," he says, adding that masks and gloves are also hard to come by. "For those who have them, they pay dear."

Truth in numbers

With millions of people now quarantined, Mr Maduro can exert more control over the population. But there is disquiet about the government's ability to cope and its willingness to report the true number of cases.

At the end of last month, journalist Darvinson Rojas was arrested after reporting on coronavirus. He was charged with "advocacy of hatred".

Doctors have also faced pressure when talking openly about the virus. "Several doctors have been directly or indirectly silenced, intimidated, threatened," Dr Pachano says.

He himself got into trouble for reporting suspected cases and for exposing the fact there was not enough PPE for medical staff. "This all makes medical and health personnel afraid to demand basic clothing to be able to deal with suspicious cases."

Feeling the pressure

Pressure is mounting within Venezuela to contain the virus but it is growing outside of the country, too. US President Donald Trump has been tightening the screws on the Maduro administration.

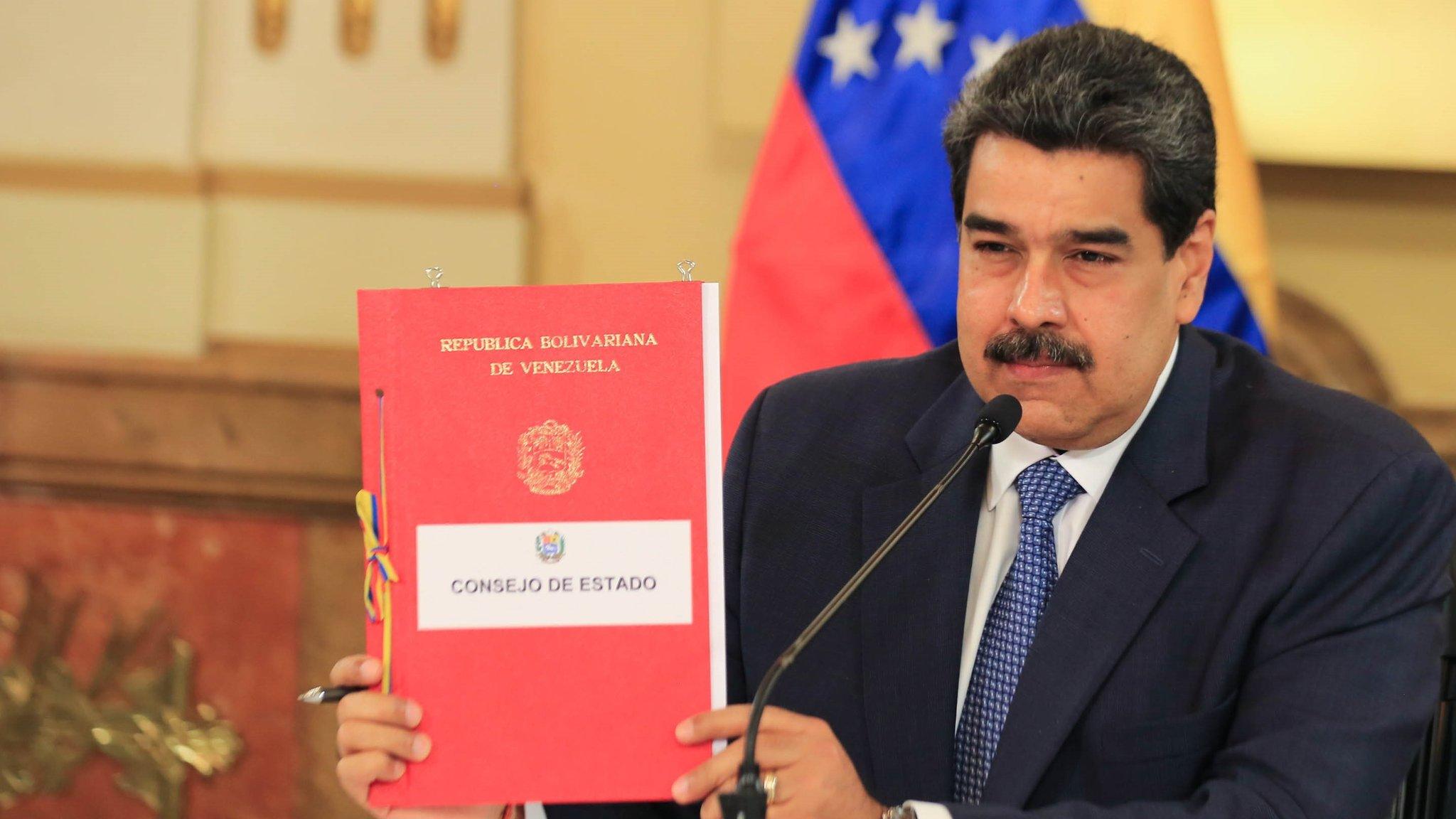

Venezuela's president has denounced the US pressure on him as "imperialist"

There is a $15m bounty on Mr Maduro after he was accused of drug trafficking by US prosecutors. The US State Department has also proposed a plan for a transitional government but Mr Maduro will not cave.

"This is not the time to be talking about regime change," says Phil Gunson of the International Crisis Group in Caracas, adding that after 20 years of the same government, even in the best of times, a change would be challenging.

"The idea that that's going to happen in the middle of a pandemic just seems to me to be mind-bogglingly absurd."

These are clearly difficult times for South America's most troubled economy. "The government probably feels a bit sweaty in the palms," says Mr Gunson. "If there's mass social unrest they are not really in a position to control it and I think that's the government's nightmare scenario."

- Published2 April 2020

- Published31 March 2020