Mothers of murdered sons fight for justice in Colombia

- Published

Beatriz Méndez last saw her son and nephew alive in 2004

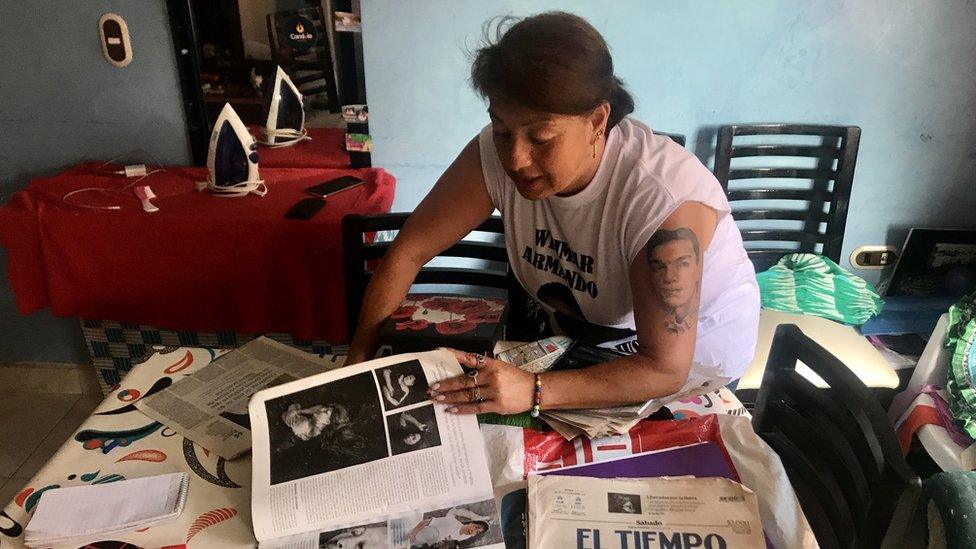

Beatriz Méndez sifts through heaps of yellowed newspaper clippings in her small home in the Colombian capital, Bogotá.

She collected them over the last 14 years as testament to her fight for justice after her son, Weimar, and her nephew, Edward, were killed.

Ms Méndez last saw them alive on 12 June 2004. The next time she saw them, they were in a morgue.

They were almost unrecognisable, bruised and battered from alleged torture. Both were just 19 years old.

For three days after their disappearance, Ms Méndez and her family searched local police stations and hospitals to no avail. Then came a call from a family member.

"On the radio they're saying they found the bodies of two guerrilla fighters in Ciudad Bolívar [a poor neighbourhood of Bogotá], they say that one is called Edward," Ms Méndez recalls.

When she and her sister went to the morgue their worst nightmare came true.

But it did not end there. After bringing home her son's body, it was a shock to Ms Méndez to find blood-stained army fatigues and boots inside the bag of clothes the morgue had sent her home with.

Photos of her son feature prominently in her home

For four years, Ms Méndez was in the dark about how her son and nephew had been killed. Then she heard a group of women talking on a radio programme about cases similar to those of Weimar and Edward. She got in touch with them and joined their collective, the Mothers of False Positives (Mafapo).

False positives is the name given to the killings of young men - mainly from poor families in Bogotá and its surroundings - carried out by the Colombian army. The army's aim was to pass them off as left-wing Farc rebels to boost its kill rate and give the impression it was winning the armed conflict against the group.

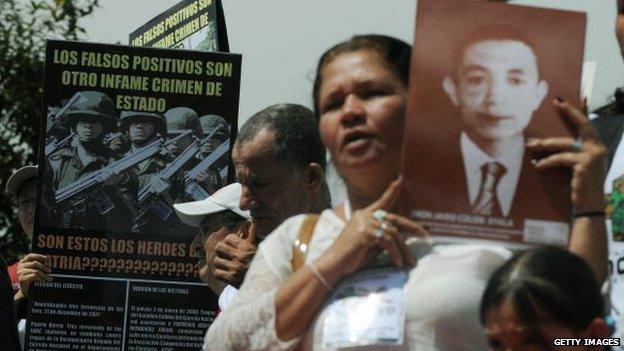

The false positives scandal caused outrage in Colombia when it first broke in 2008

The victims were lured to rural parts of Colombia with promises of job opportunities, and their bodies were later found dead in mass graves.

Some had been dressed in guerrilla fatigues like those used by the Farc, others had had weapons placed in their hands.

A 2018 study by Colombian academics estimates that up to 10,000 people were killed in false positives, the majority between 2002 and 2010. Government figures put the number much lower.

For over a decade, Mafapo has been fighting to bring those responsible for the killings to justice.

In October, they presented a report before the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP) in Bogotá.

Conflict and peace in Colombia

The conflict with Farc guerrillas saw more than 200,000 people killed, and wracked Colombia for more than 50 years until the signing of a peace deal in November 2016.

Victims of violence carried out by either side of the armed conflict can turn to a special tribunal that was created under the peace agreement with the Farc rebels.

The Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP) is a transitional court system which has been put in place for 10 years, and which was set up to try all participants in the conflict, be they Farc rebels or state actors.

Those who admit to their crimes up front will avoid jail time, but will be required to contribute in other ways to reconciliation - such as participating in programmes to remove landmines, build key infrastructure or construct monuments.

In recent months, the JEP has exhumed dozens of bodies from a mass grave in the Antioquia region of Colombia as part of its investigation into the false positives.

The director of the Americas division of pressure group Human Rights Watch, José Miguel Vivanco, says that "false positive killings amount to one of the worst episodes of mass atrocity in the Western Hemisphere in recent years".

He says that the excavation of mass graves may help bring to light further evidence of the scope and systematic nature of these crimes, while providing some relief to the relatives who have been searching for their loved ones.

"But the real test is whether the transitional justice system will be able to hold to account top brass officers who have escaped justice for over a decade," Mr Vivanco argues.

Ms Méndez wanted something to remember her son by

Back at her home in Bogotá, Ms Méndez shows off a new tattoo: a portrait of her late son on her shoulder.

"I wanted something to never forget him by. It hurt, but not as much as the pain of losing him," she says.

The mothers' collective is involved in many activities, mostly to help them deal with the grief of losing their sons.

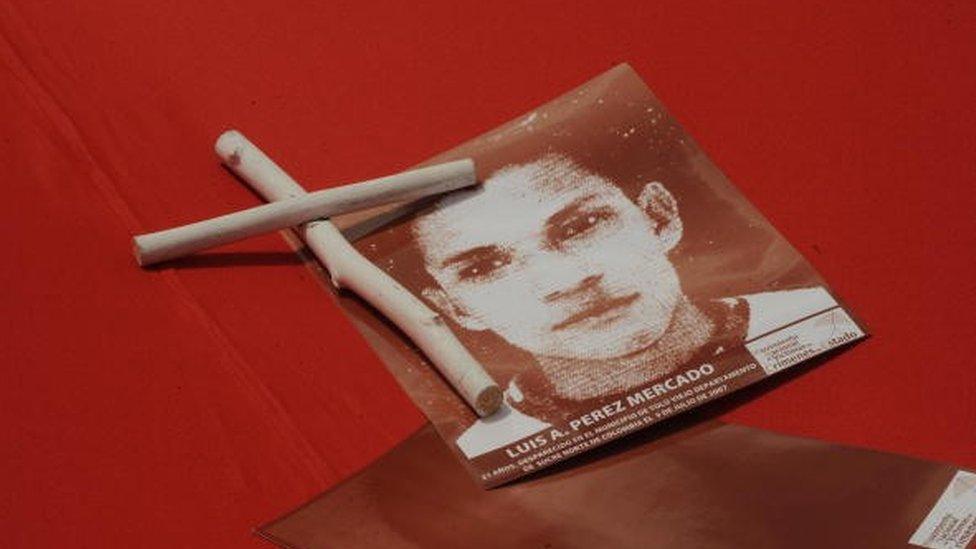

The latest one is creating woodcuts with the images of their son's faces. As well as Ms Méndez, 61-year-old Blanquita Monroy is at the workshop.

Blanquita Monroy finds solace in woodcutting

"It's what's helped the most with the pain over all these years. When I start working on the wood it helps with everything, all my problems go away," she says.

The last time Ms Monroy saw her son, Julián, was on 2 March 2008, when he left their home in Soacha - an impoverished municipality outside Bogotá - to meet somebody about a job opportunity.

"He told me he wouldn't be long. But we never heard from him again," Ms Monroy says.

She found out six months later that 19-year-old Julián was dead. He was found in a mass grave with around 20 other young men in Ocaña, a north-eastern town more than 600km (375 miles) from Bogotá and one of the main hotspots for the false positive killings.

The mothers want to put an end to the impunity surrounding their sons' killings

"The hope we have as Mafapo is that they [the army] tell the truth," she says of her hopes for the mothers' case at the transitional justice court.

"Why did you kill them? Who gave the order? And why did they give the order?" she reels off the questions she wants answered.

Although the mothers are not convinced much will come of the proceedings, Ms Monroy sees it as "a little window to the beginning of the truth".

Ms Méndez says that whatever happens, the mothers in the collective will not be giving up on their quest for justice anytime soon.

"If I die in search of the truth, my struggle won't have been in vain," she says.

"I'll be part of the memory and history of Colombia, for the young people of the false positive killings - especially my son and my nephew."

- Published3 March 2019

- Published24 June 2015

- Published13 April 2015