Mexico crime: Could this become the bloodiest year on record?

- Published

Police in Mexico have faced a surge of violence

In the two years since Andrés Manuel López Obrador won the presidential election in Mexico by a landslide, the country has endured many violent moments.

But recent months have been especially bloody and brutal.

On 7 June, an astonishing 117 murders were recorded in 24 hours, making it the country's most violent day of the year so far. The previous high had been on 20 April, when 114 homicides took place.

If the trend set in the first four months continues, 2020 could become the bloodiest year on record.

Impunity

Rather than the numbers, though, it is the sheer brazenness of these attacks which stands out.

Criminal gangs have targeted low-level cartel foot soldiers and high-profile political figures alike. There have been both mass killings and carefully planned assassinations.

"This is a cost that we are now paying for years and years of continued, almost perfect impunity in Mexico", says Falko Ernst, a senior analyst at Crisis Group.

The street in which the attack happened was littered with bullet casings

A group of gunmen reportedly disguised as construction workers pulled up in a truck and attempted to assassinate the city's police chief, Omar García Harfuch.

During a fierce gun battle between the gang and his security detail, three people were killed, one of them a woman who was on her way to work.

Omar García Harfuch survived the attack on his life

Despite being shot three times, Mr García Harfuch survived the attempt on his life which he later blamed on the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG).

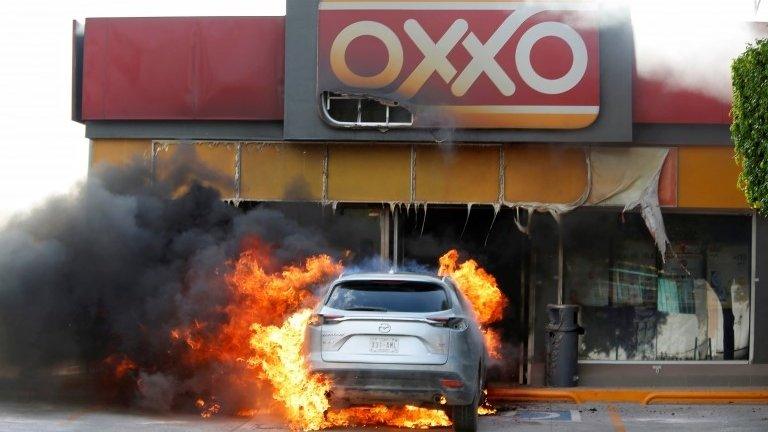

The same group was also implicated in one of the recent shooting sprees, too. In Irapuato, in the state of Guanajuato, gunmen entered a drug rehabilitation centre and forced patients and staff on to the floor before opening fire on them as they lay prone on the ground.

Twenty-six people were killed in the shocking incident, believed to be part of a worsening turf war between the local Santa Rosa de Lima gang and the CJNG.

More than two dozen people were killed in the attack on the drug rehabilitation clinic

Once considered one of Mexico's most peaceful states, Guanajuato is increasingly among its most dangerous as the CJNG gradually extends its influence into new areas of the country.

"They have been very aggressive from the outset and have gotten away with killing federal forces, including lots and lots of police in Guanajuato, and the shooting down of military helicopters," explains Falko Ernst.

Mr Ernst argues that the underlying problem is the blurred line between state security forces and organised crime. "Even though the Jalisco Cartel has publicly declared itself as an enemy of the state, there are still a lot of shady ties with fragments of the state, including at the federal level," he says.

Critics of President López Obrador argue that, despite its promises, his administration has not tackled the twin issues of impunity and state involvement in criminal activity or developed any kind of coherent security policy.

The BBC repeatedly requested an interview with the public security ministry but no-one was made available for comment.

Chilling memories

For many in Mexico, the period between 2009 and 2011 brings back chilling memories.

Widely considered some of the worst years of the country's drug war, it was a time of ferocious internecine violence between powerful cartels. Many communities lived under almost constant curfew and gun battles for territorial control were commonplace.

Yet today, the monthly homicide rate is far worse. The bloodshed seen in 2019 and this year suggests Mexico may have already slid back into a familiar pattern of violence, even as some regions remain under lockdown over the country's worsening coronavirus outbreak.

One of the particular complications of Covid-19 in Mexico has been that police and security resources have been stretched to breaking point.

"Security forces in Mexico were already very weak to start with and now they're being overwhelmed by the pandemic," says Mexican security analyst Alejandro Hope.

Manpower has been turned towards managing one of the most severe outbreaks in Latin America, he says, instead of tackling violent crime.

You may also be interested in:

The plane was destroyed by fire after coming down on a road

The pandemic was arguably an opportunity for the state to reassert itself in many parts of Mexico.

However Alejandro Hope believes that chance was missed. "I'm not sure [the cartels] will come out of this stronger than they were before but clearly they will not come out any weaker either."

He points to the recent killing of a federal judge, Uriel Villegas Ortiz, as a sign of just how far things have sunk.

In a disturbing scene last month, Judge Villegas and his wife were murdered in front of their two daughters. He was only the second federal judge to be killed since 2006.

One case he had presided over was against Rubén Oseguera, son of the leader of the CJNG, Nemesio "El Mencho" Oseguera.

Mexico's interior secretary was among those who said that Judge Villegas's murder would not go unpunished. But the ease and apparent impunity with which it was carried out suggest otherwise.

Rather than sliding back towards the worst years of the drug war, Mexico may have already reached that low point some months ago.

- Published8 July 2020

- Published2 July 2020

- Published30 June 2020

- Published27 June 2020

- Published22 June 2020

- Published17 May 2020

- Published4 May 2020