The rape survivors facing an ‘impossible choice’ in Brazil

- Published

Paloma, who works in occupational safety, said she did not know what to do after she was raped

Paloma had just cobbled together enough money for a clandestine abortion when the coronavirus pandemic shuttered much of Brazil.

The 27-year-old had been raped late last year by an ex-boyfriend who remained a close family friend. The mother of two found out she was pregnant a few weeks later, after moving from her native Bahia to Minas Gerais, a nearby state, for work.

"I didn't know what to do," recalls Paloma. "The only thing I was certain of was that I didn't want this child."

Brazil has strict laws on abortion. Terminations are only allowed in cases of rape, when the mother's life is at risk or when the foetus has the defect anencephaly - a rare condition that prevents part of the brain and skull from developing.

While Paloma was entitled to an abortion by law, like many women in Brazil, she was not entirely clear on her rights.

She worried she would have to report the rape to the police in order to access a legal abortion - a tactic commonly used to steer women away from the procedure. But she feared retaliation from her rapist. "I was really worried about the safety of my children," she explains as her decision to save up for a clandestine termination.

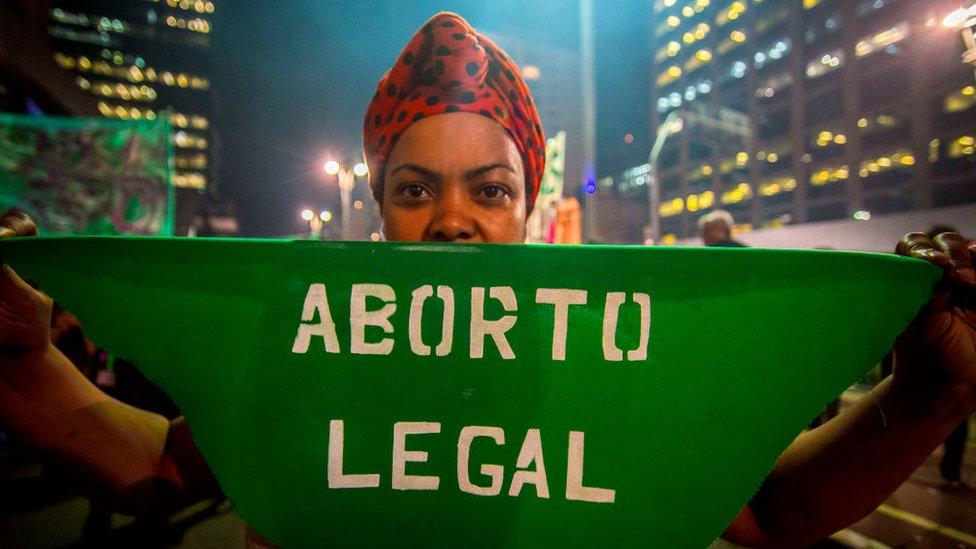

Many pro-choice protests have been held in recent years in Brazil

But the issue faces strong opposition, especially from religious groups

Clandestine abortions are risky: when performed without sound medical oversight, they can lead to complications and endanger women's lives. If found out, women can also face up to four years in jail.

But Paloma did not know where else to turn and started saving the 3,700 reais ($660; £515) she needed for the clandestine procedure - a sum that is over three times Brazil's minimum monthly salary.

A doctor was going to fly in from Rio de Janeiro, over 900km (560 miles) away from her new home in Minas Gerais, to perform the termination. Then, the Covid-19 pandemic paralysed Brazil, shutting airports, bus stations and health centres.

By late April, Paloma was over 23 weeks pregnant. "When everything closed, it became really difficult to travel - it all became so complicated," she recalls.

With the process dogged by delays, Paloma turned to the internet in search of options one last time. She stumbled upon Milhas pela Vida das Mulheres, a network helping women access safe abortions.

The group helped her understand her rights and pointed her to one of the few legal abortion clinics still operating during the pandemic. For Paloma, it was a fortuitous turn of events. "I was going to risk my life and I may not have been alive today," she says of the clandestine abortion she was planning to have.

Curbed access

Many Brazilian women have not had the same luck as Paloma during the pandemic. Early on, the crisis sharply curtailed access to legal terminations as many abortion clinics shuttered. Data collected by activists suggests that, of the 76 registered clinics providing legal abortion across Brazil, only 42 remained open during the pandemic.

Abortion in Latin America

One of them is Nuavidas, the health hub in Uberlândia assisting victims of sexual violence where Paloma's abortion was performed. "The pandemic became an excuse to unravel the rights of women," says obstetrician Dr Helena Paro, the co-ordinator of Nuavidas.

Sandra Leite is the co-ordinator of a centre for female victims of violence at Recife Women's Hospital, which also remained open during the pandemic. She says the pandemic made it more difficult for vulnerable women to reach a clinic.

Sandra Leite works at Recife Women's Hospital

During quarantine, "women had more difficulty leaving the house" to seek help, she says. "And in some cases, their attackers were inside the house with them, so they couldn't seek healthcare." She says the centre where she works saw a decline in patients, even though it was one of the few to remain open.

But she says that now that lockdown restrictions have eased, demand for legal abortions has increased. "We're seeing that women have suffered more violence while in isolation at home with their aggressors," Ms Leite says.

Arbitrary limits

At Dr Paro's clinic, the number of women seeking legal abortions has doubled recently. And many women - like Paloma - are arriving with more advanced pregnancies, likely because they could not seek or access help during the pandemic.

Dr Helena Paro says more women are seeking abortions after the lockdown

"At times, these women have had to travel long distances to access this right," Dr Paro says. "And that's often why they're arriving with more advanced pregnancies."

This could pose yet another barrier for women. Abortions after 22 weeks are controversial and Brazil's health ministry advises against them, citing heightened risks for the mother's health.

Dr Paro says that while the 22-week limit is "not based in science" nor enshrined in Brazilian law, most clinics refuse to carry out the procedure beyond that point.

Dr Paro's clinic is one of just a couple of facilities across Brazil that perform abortions beyond 22 weeks.

She calls the 22 weeks an "arbitrary limit" which she argues many doctors use as "an excuse to refuse an abortion that they are already against".

"So if a woman passes [22 weeks], she will have huge difficulty finding an abortion clinic in Brazil today" to perform a termination, Dr Paro explains.

Further blow

Even before Covid-19 struck Brazil, abortion rights were coming under attack.

With few clinics across the vast country, most women already struggled to access legal abortions, says Gabriela Rondon, a researcher and lawyer with Anis, an organisation promoting women's rights.

Complications caused by clandestine abortions cause unnecessary deaths of women, activists say

In the poorer north, there are just two clinics for a region of over 17 million people.

"Many women don't have a clinic nearby, especially women in rural areas," Ms Rondon says. "And there's also a lack of information - oftentimes, women are not told they have this right."

She adds that in practice, many clinics say they offer the service but instead "employ a series of barriers, which either delay accessing an abortion or make it impossible".

When women do reach a clinic offering legal abortions, they are often treated with hostility or aggressively questioned. Some are turned away by doctors who refuse to carry out abortions on "conscientious" grounds.

Women seeking a termination are now facing a new hurdle too. In August, the government released new guidelines instructing clinics to report cases of rape to police - even when victims do not want to.

Ms Leite believes the guidance will discourage women who have been raped from seeking abortions they are entitled to by law.

"All of this work that was done over the years - today we're seeing it crumble."

You may want to watch:

Inside the secret world of Brazil's WhatsApp abortions

- Published18 August 2020