Coronavirus: The realities of schooling in rural Brazil

- Published

Jaydson Silva has been studying at home with the help of his mother

The coronavirus pandemic has changed the way children are learning across the planet.

In Latin America and the Caribbean, 97% of children are still not having face-to-face classes, according to estimates by the United Nation's children's agency, Unicef. That is around 137 million students.

On average, children in Latin America have lost nearly four times more days of schooling than in other parts of the world, Unicef says.

The challenges faced by pupils and teachers in Jucurutu, a rural area in the state of Rio Grande do Norte, in north-eastern Brazil, show why it is so difficult to provide classes amidst the pandemic.

Rural areas have been struggling to continue providing schooling

Even after 22 years in the classroom, teacher Ivonaldo Lopes de Araújo says that 2020 has been a steep learning curve.

Gone is the school building, his workspace is now a computer screen at home. And his 24 students are now at the end of a Whatsapp message instead.

You may also be interested in:

Ivonaldo says he and his colleagues panicked a bit at first, not quite sure how to adapt their classes. But he has got into the swing of things now, even if his workload has doubled.

Ivonaldo now speaks with his pupils via Whatsapp

"You don't have a set time to stop," he says, as he checks his phone messages over a coffee.

"I can't say, 'OK that's it for today' because I'm constantly in touch with students that need support. There's no timetable - it's afternoon, night, morning, each and every day."

Rural challenges

The children in Ivonaldo's class at the Joaquim das Virgens Pereira school are aged from six to 10, as is typical in smaller village schools in Brazil. So he has to think up different ways of teaching, depending on their ages.

Zoom classes are not an option for Ivonaldo

Not only that, half of the class do not have internet. So Zoom classes are not an option. It is hard to keep a tab on everyone's progress when they are not in school.

"I'm constantly thinking, how am I reaching out to the kids? Will they keep studying?" he says.

"Many stop doing their homework. For those who do keep going, I can check how they are doing, but with some, even those with internet, you send the activities over and they never send it back so it's hard to evaluate them."

Homework by bike

Ivonaldo's job has evolved somewhat since the pandemic. No longer is he just Professor Ivonaldo, he is also had to take on the role of postman, getting on his red motorbike every week to take school work to his pupils' homes.

Ivonaldo drops off homework on his motorbike

Today, his first stop is the school. It is a simple red-and-white building with two classrooms and a little kitchen. The plastic desk-chairs sit empty - that is, apart from six mothers waiting to pick up manila envelopes with their children's names on them.

Mothers wait to pick up the worksheets for their children

"She likes doing the activities," says Jeane Bezerra de Almeida of her seven-year-old daughter Maria Cecilia. But when it comes to the online classes, that is a bit harder.

"The internet comes from a neighbour and the signal often cuts out, so the neighbour has to pop over to connect us again."

Educational divide

The pandemic has also come at a personal cost: Jeane's sister-in-law died from coronavirus.

In the southern hemisphere, the school year starts in February or March and it ends in December. That has meant that most students have gone for nearly an entire academic year without classes.

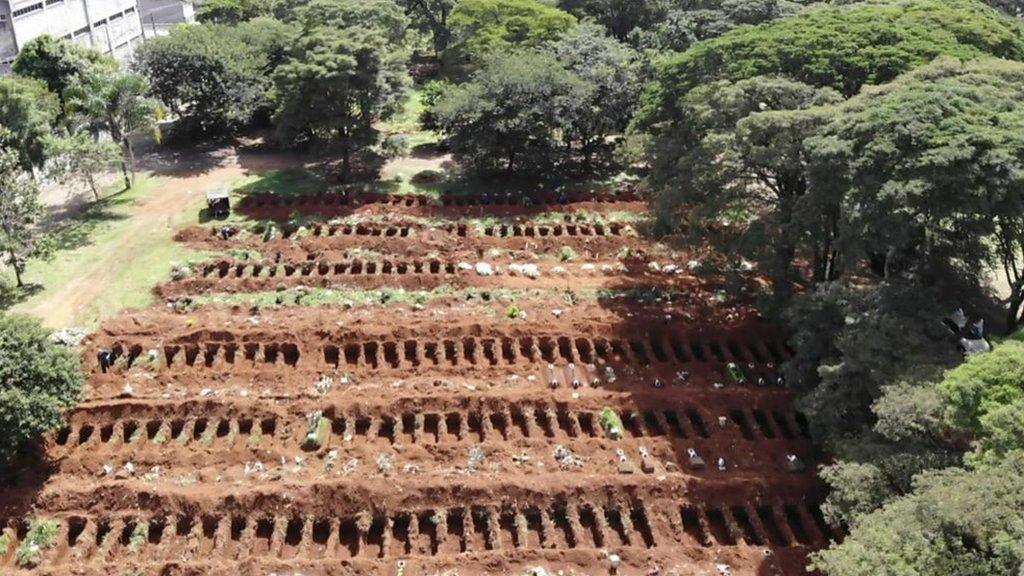

With the situation of Covid-19 still far worse than in other parts of the world, few schools have returned to face-to-face classes and there are still no promises of going back in the new year either, especially if there is a second wave here.

With face-to-face classes unlikely to resume anytime soon, Ivonaldo faces more bike rides to deliver school work

This is the most unequal region in the world, and Covid-19 has brought out those inequalities when it comes to education.

"Schools also provide important services beyond education, such as school feeding programmes and health programmes," says Margarete Sachs-Israel, a regional educational advisor at Unicef.

"The impacts go beyond education and have a long-lasting effect that it's not just about not learning this year, but will have an implication for the future of an entire generation, that will have consequences for society as a whole."

Home-schooling

Before the midday sun becomes too intense, Ivonaldo makes his last stop. Eight-year-old Jaydson Silva lives with his mum Jacilene and dad Avanilson in a simple house made of wood and mud.

Jaydson Silva helps his mum Jacilene and dad Avanilson by earning money filling in potholes

When he is not filling in worksheets, he spends his days playing - and says he also helps his parents earn money by filling holes in the road. This is the reality of so many other children across the region, too.

For his mum Jacilene though, teaching her son has clearly opened up her world in a way.

"My dream was always to be a teacher," she says shyly. "I didn't finish my studies. I would love to continue - if my husband let me. He's a bit jealous."

Jaydson spends much of the day playing but he misses his school friends

For Jaydson, the classroom is where he is happiest. "I prefer school, because it's better," he says. "I can talk to my friends."

But while Covid-19 continues to loom over this region, there is no talk yet of returning. Which means Ivonaldo will remain on the road - for now.

- Published9 October 2020

- Published8 October 2020

- Published16 April 2020