Chile's Mapuche indigenous group fights for rights

- Published

The Mapuche flag was a common sight at protests demanding a new constitution

When people in Chile took to the streets last month to celebrate an overwhelming "yes" vote in a referendum on whether the constitution should be rewritten, many waved the Mapuche flag.

The Mapuche make up about 12% of Chile's population and are by far its largest indigenous group. They have long been fighting for recognition as Chile's constitution - drawn up during Gen Augusto Pinochet's military rule - is the only one in Latin America not to acknowledge its indigenous people.

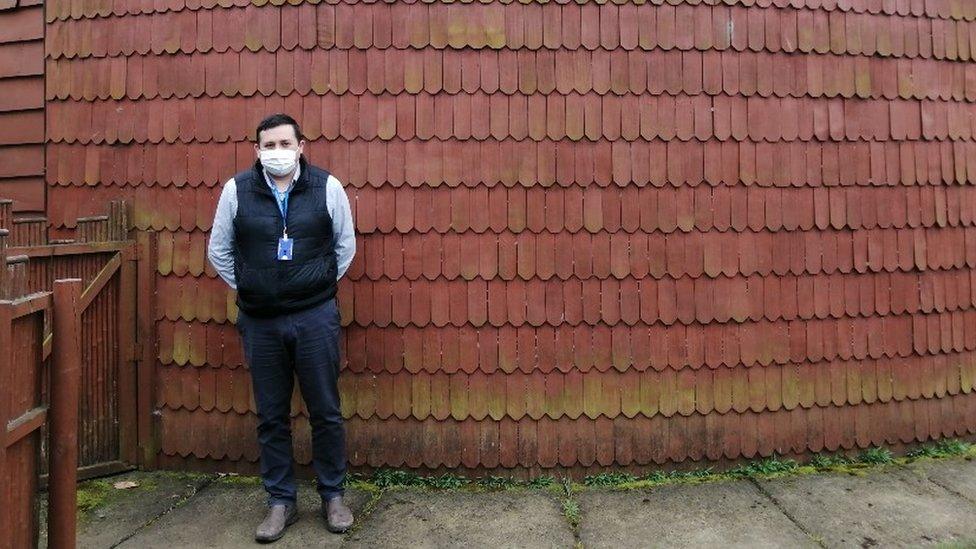

But Councillor Marcelo Vega Melinao thinks the "yes" vote in the referendum could signal the start of a new era. "I want all the indigenous communities to finally be recognised in the new constitution and represented in the government" he tells the BBC.

Who are the Mapuche?

Before the arrival of the Spanish in the 16th Century, the Mapuche inhabited a vast swathe of land in southern Chile

Renowned for their ferocity, they successfully resisted conquest until the late 19th Century, when they were rounded up into small communities

Much of their land was sold off to farmers and forestry companies

About 12% of Chileans define themselves as indigenous, most of them as Mapuche

Mr Vega is the first Mapuche to be elected to the city council in Victoria. The city is located in the Araucanía region, the homeland of many of Chile's two-million-strong Mapuche population.

"The government needs to start listening to us and return our land. It's like an open wound that won't go away," he says.

The land he refers to is vast swathes of Mapuche territory handed to wealthy business families during the rule of Gen Pinochet between 1976 and 1990.

In the 1990s, following Chile's return to democracy, the government said it would hand back some of the land to the Mapuche. But progress has been minimal, with owners reluctant to sell and red tape slowing down proceedings.

The delay is further fuelling resentment which in turn has triggered violent incidents in the region. There have been arson attacks on lorries carrying timber for forestry companies, shootings, and take-overs of government buildings.

More about the tension:

While many non-indigenous people blame the Mapuche for the violence, the president of a pro-business group in the region, Luciano Rivas, says it is not that clear-cut.

"I think we should call them by their true name: criminals," Mr Rivas argues. "Frequently they wear masks, so there is no way of telling who they are," he adds.

Mr Rivas and other locals have different theories as to who may be behind the violence: some think drug traffickers are terrorising the region so as to turn it into a no-go area where they can have free rein while others suspect non-Mapuche people of torching their own lorries to make money through fraudulent insurance claims.

Amid the rising tension and the finger-pointing, there are Mapuche community leaders like Minerva Castañeda who are fighting not just for Mapuche land rights but also for their culture and traditions to be recognised in the new constitution.

Minerva Castañeda wants Mapuche traditions to be given more recognition

"I want more representation for us in the government and money to be ring-fenced to finance our healthcare and education," she tells the BBC from her home in Temuco, the capital of the Araucanía region.

Ms Castañeda says that government guidelines and regulations often get in the way of Mapuche traditions, such as a ritual in which new mothers bury the placenta after their baby's birth.

"As a Mapuche woman I was not allowed to have the kind of traditional birth that I wanted, or to take my placenta home with me," she recalls.

Recent governments have flip-flopped on the issue with the administration of President Michelle Bachelet allowing the practice, only for the government of her successor in office, Sebastián Piñera, to ban it.

Ms Castañeda also wants more Chileans, be they Mapuche or not, to have easier access to traditional healers, known as Machi.

She says that the Machi she wants to consult for her vast knowledge of medicinal plants is hard to get to because she lives out in the countryside down a bumpy dirt track road.

Minerva Castañeda would like to consult Machi Juana, but getting to her is not easy

Many Machi have a vast knowledge of medicinal plants and their curative powers

The Intercultural Hospital in the city of Nueva Imperial is one place in Auracanía where working together and accepting each other's cultures is celebrated. One wing of the hospital offers Mapuche healthcare, and the other, conventional medicine.

Cristian Arañeda, who manages the conventional medicine wing says that his Mapuche colleagues should get more recognition. "People have a right to be treated by these kinds of specialists," he says.

Daniel Melillán is the manager of the Mapuche wing and proudly shows off the ruka, a traditional hut where the Machi hold healing ceremonies for their patients using plants and tree bark.

Daniel Melillán is proud that the hospital offers both conventional and indigenous treatments

Both men agree that the government needs to provide more resources so that patients across Chile can have more access to hospitals like theirs.

But for Mapuche business leader Hugo Alcaman it is not just a question of resources but of attitudes.

Hugo Alcaman thinks it is time for a change of attitude on the part of non-indigenous Chileans

He says that the Mapuche have learned to live in both the indigenous and non-indigenous culture, but that non-indigenous Chileans refuse to adapt to the Mapuche ways.

He argues that non-indigenous Chileans have never fully embraced their origins, instead looking to Europe for their culture and architecture. "When will they learn to accept that their roots are here with us, the original people in Chile - the Mapuche?" he asks.

Mr Alcaman does not think that a new constitution will bring much change. "The government always talks about dialogue, but what they are really doing is trying to persuade us of their point of view rather than listening to what we want," he argues. He says he doubts that it should be any different this time.

But with all of the members of the assembly which will draft the new constitution to be chosen by popular vote, some Mapuche are hopeful they will have representation.

"This is our chance to have our voice heard and to make changes," Ms Castañeda says.

You may want to watch:

Chilean Mapuches performing modern-day hip-hop in their Mapundungun language

- Published21 December 2018

- Published16 November 2018

- Published12 March 2018

- Published17 January 2018

- Published25 October 2017