Three lives, one message: Stop killing Mexico's transgender women

- Published

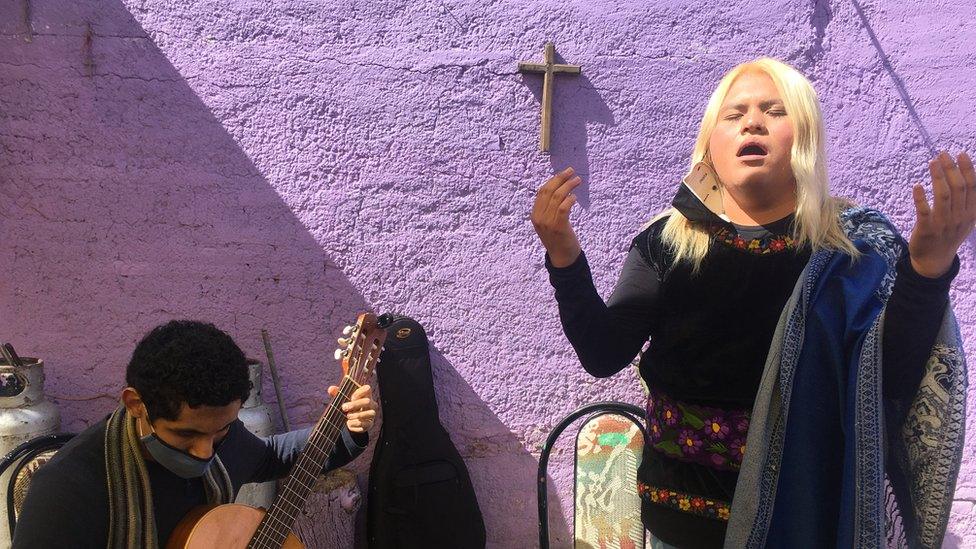

Ariel Hernandez Serrano hopes her music brings visibility to the trans community in Mexico City

Mexico is the second most dangerous country in the world to be transgender, according to human rights groups. Only Brazil has higher rates of transphobia and violence against the trans community. Most attacks go unpunished, including murder. Three women are fighting for change.

In a small paved patio beneath a bust of the Virgin de Guadalupe, Ariel Hernandez Serrano's lilting voice echoes across her rundown corner of Iztacalco, the most densely-populated borough in Mexico City.

Accompanied only by a classical guitarist, she performs a poignant rendition of a Mexican folk song, La Llorona, meaning The Weeping Woman.

The music itself originates far from the bustle of the capital, in the south-eastern state of Oaxaca, and Ariel's version includes phrases in the indigenous Zapotec language.

Bleached-blonde and invariably smiling, Ariel says she is trying to achieve two things with her music: to help preserve Mexico's fast-disappearing indigenous languages, and to give greater visibility to the country's marginalised trans community.

Last year, she became the first transgender woman to perform inside the presidential palace of Los Pinos.

Ariel performed in the presidential palace last year

"Maybe I can do something positive to educate and sensitise people," she says between songs. "I've realised that art and music can erase prejudice, stereotypes and ignorance."

Being transgender in Mexico is far from easy, Ariel says. "This is a poor neighbourhood but it's safe," she explains as we walk the streets near her family home. "Luckily I've never been subject to any physical aggression, although I sometimes receive insults and stares. But most people respect me here."

But while her neighbours know and appreciate her, it is a very different story elsewhere in the sprawling city, let alone in rural and less tolerant parts of the country.

Ariel is well aware of the risks involved in fighting for greater visibility for transgender people. "I'm not dedicating my life to trans activism," she clarifies, preferring simply to be considered a musician. "But I have great respect for those who do because they put their lives on the line."

That is no exaggeration in a patriarchal society like Mexico's. As many as 98% of murders in the country go unsolved and unpunished, and the authorities often show little inclination to investigate the killings of transgender women.

Kenya Cuevas is one of Latin America's best-known transgender activists

One person who is trying to fix that is Kenya Cuevas. Unlike Ariel, she does fully identify as an activist, despite the dangers.

When we met outside a metro station, she arrived with a state-appointed bodyguard after receiving death threats for publicly challenging Mexico's entrenched impunity.

The back of Kenya's right hand is covered by an intricate tattoo and her nails are painted bright yellow. As she emerges from the car, the sex workers around the station immediately flock to her to ask questions and seek help and advice. She knows these people well. She used to be one of them.

Her life story reads like the description of a character from a film by Pedro Almodóvar, the Spanish director who made his name with colourful melodramas on taboo topics.

Abused and mistreated as a young boy, Kenya left home aged nine and transitioned as a teenager. On the streets, she was soon led into prostitution and drug abuse. By her twenties she was a drug addict, HIV positive, and incarcerated.

But since her release, Kenya has turned her life around to become probably the best-known transgender activist in Latin America. After a friend - another transgender sex worker called Paola Buenrostro - was killed in front of her in 2016, Kenya founded Casa de las Muñecas Tiresias, the only shelter exclusively for transgender women in Mexico.

Over the years, she has carried out various health campaigns, from distributing free condoms to sex workers to giving out meals to the homeless.

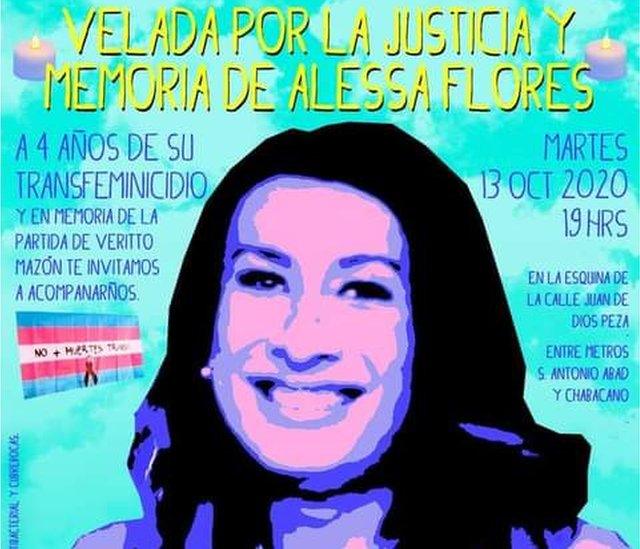

A poster for a memorial event on the anniversary of the killing of transgender woman Alessa Flores

Recently though, her relentless energy has been focused on urging the attorney general's office to reform the penal code to recognise trans-femicide as a hate crime. She says the government of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has been far more receptive to such changes than Mexico's previous administrations.

"Through everything we've done and built, we have achieved greater visibility and more openness among the governments [at state and federal level]," she says.

"It's been historic. Through Paola's killing, we found an intersection between ourselves and the authorities to identify the issues we face and then attend to them."

The road ahead is still long but getting started on it was the most important thing, says Kenya.

For many queer folk, however, any legal reforms come too late.

Cecilia Flores with her daughter Alessa, who was killed in 2016

On the phone from Tabasco, the president's home state, Cecilia Flores struggles to explain exactly what happened to her child. She is the mother of Alessa Flores, a transgender woman who was killed a few weeks after Kenya's friend, Paola.

"I know it happened in a hotel room," she says of her daughter's murder. "But hotels have cameras, and someone must know who killed her. So far, the police have basically ignored me."

If ever given the chance to speak directly to President López Obrador, Cecilia says she would urge him to make the justice system fairer for everyone, regardless of their gender identity:

"These girls just aren't treated as equals," she says.

You might also be interested in:

How transgender influencers like Thiessa are changing Brazil's advertising industry